Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

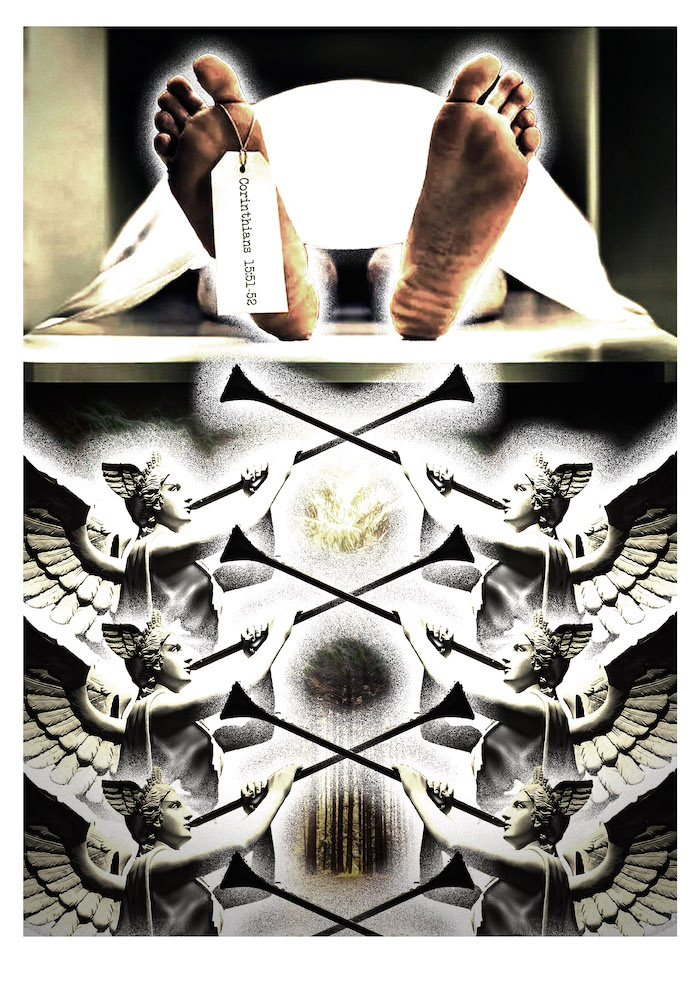

HONORABLE MENTION, Fall 2024

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY DEIRDRA McAFEE

The tale travels from campfire to campfire; it rides in sideshow caravans, in the fleabitten bedrolls of tramps and beggars, the lonely pockets of runaways, the ragged purses of whores, the lays of troubadours, the beckoning bottles of traveling quacks, the restless hearts of vagabonds, the cold, calculating eyes of brigands. The whole affair, whether legend, rumor, or twisted whisper, scales crooked mountain paths and trudges mired valleys. Cutpurses and rakes claim he stole her but ignore her eager consent. Mountain-roaming Romany swear she ensnared him with spells but believe she needed tricks and traps.

People ask me to tell the tale, and I tell them what happened; I tell them how and when and who. But I never tell them why. I, the solitary, who belongs nowhere, who asks alms in return for blessings, who seeks neither kingdom nor tribe, offer you the authentic tale in all its trouble and splendor.

* * *

After they gathered flowers, the harvest’s daughter and her girlfriends drowsed in a meadow full of columbine and bee-song. They dreamed maidens’ white dreams spiked with whiffs of wood-smoke from a nearby shepherd’s hut.

Death, meanwhile, burst in full panoply from a fiery fissure—flaming chariot, shrieking steeds, cloak of starry darkness, body burnt at the edges but touched with brilliance.

The others hid their eyes and fled; mortals who behold him cannot speak of it. But she, the harvest’s daughter, stood her ground. Afraid, but, unwisely, not terrified. Or perhaps simply transfixed by the fire, the brilliance, the shining cloak falling upon her like fate, inescapable. She, so familiar with life, didn’t recognize him. He, far more sophisticated, conversant with costs and consequences, watched himself do what he didn’t expect and couldn’t believe: lean down and curl his iron arm around her. Seize her, almost casually. Swing her up one-handed, submit to her embrace, share the deep kiss of entrancement, and take her down.

They descended to the dark and murky ancient destination. They waded the poisoned river, disdaining the blind boatman. Death clasped this live girl closer, letting her live on, warm breath thawing his icy heart, soft skin tender against his tough hide.

At Death’s dwelling, in his vast and gloomy stone bedchamber at the end of a chill and murky hall, he kissed her awake. It was time, he told her. He’d take care of her. This he meant, but she found reassurance unnecessary. Weary of childhood, she had no plans. She was ripe. Free of light’s harsh distraction, they undressed each other. He, who sees in the dark, knew he’d found his fated bride. He lit a single tall black candle. He gleamed in its glow till she found him.

He insinuated himself here and there, tasted her delicious places, examined her treasures and laid bare his own. The mutual search moved them as they moved. Slow, adroit, sympathetic, attentive, Death was a fabulous lover—even she, so inexperienced, realized that. He knew, since he dwells in all things always, everything there was to know about flesh, and even something about love, though mainly that it decays.

In the moment of consummation, he almost forswore his essence and laughed. (The deepest danger: Death’s necessary attitudes are irony and distance. Delight destroys them.) Thus she became the girl who slept with Death but survived. She loved what they did. So did he, who’d never hitherto taken note of any being in a body. They repeated the enjoyable activity subsequently and often. He couldn’t stifle occasional sepulchral snickers. She didn’t care if she ever saw daylight again.

He didn’t mind that the harvest’s child was green and naïve. He encouraged her curious and tender investigations. What she learned spurred him as it did her. She grasped what older, more experienced lovers sometimes miss: mutuality is the ultimate aphrodisiac. Her body alight, her mind afire, her will aswoon, flushed and swollen everywhere, she knew she should leave. Her mother would wonder. But. She knew he needed her. Knew she wanted him.

They whiled away sunless days in his high black-curtained bed. They touched each other languidly until they burned, watched each other by the guttering glow of that candle, whose light, like their passion, rose and fell but never went out, and, at loud last, when hot propinquity’s pleasures grew unbearable, embraced.

Death had a hearty appetite. He’s well known to be inexhaustible, which appealed to the girl, because his vigor, imagination, and unwearying attention were inexhaustible as well. He’s well known, too, to be insatiable. Every few hours, when their cries ceased echoing through Death’s halls, when the sweat of their exertions dried and languor replaced lust, Death rang the bedside bell.

A sooty servant brought food and drink: always something different, rich rare foods and strange brews. She, however, living on love, never partook. Until one murky midday the servant brought steaming espresso and a chilled ripe pomegranate. Death tossed back the espresso in one black gulp. He ripped open the Tyrian fruit. From the wound, he scooped a fistful of wet, shiny seeds. Grinning, he licked almost all of them down. Grinning wider, he leaned to feed the last one to the girl. She let him, which for some reason inflamed them both anew.

On each of six sweet days, she opened her lovely mouth to a single sweet seed. Parted her ruby lips—the seeds alone were redder and juicier—and plied her saucy tongue. Death pushed a single succulent purple-red pip ever so slowly, ever so gently, from his mouth into hers,. Tenderly. Temptingly. Her white teeth met upon the seed. Its vivid juice dropped from her full lips to stain her chin. After which they fell to, and fell together, again and yet again.

* * *

The girl’s mother. as it happened, did not wonder where she was. As all mothers do—they, after all, remember how they got that way—she knew. At least in a general sense. When the girl failed to reappear, the harvest goddess feared, or knew, that darkness disappeared her daughter.

An explosion of violets, lilies, pansies, and dandelions littered the meadow. On a scorched patch of ground, broken half-finished daisy-chains intertwined with dark malodorous earth. The signs spoke: wilted blossoms, trampled grass, the tang of sulfur, the scent of ozone after a storm.

She sank upon this destruction in her golden robes to ponder her daughter’s absence. Fears for her child furrowed her beautiful brow. Mothers know too much about what’s possible. The earth itself, meanwhile, her special care and domain, waited in cool green liveliness, with an indifference almost blasphemous.

The goddess wept with dread. She took the birds’ voices, locked up the wind, shredded the sprouting leaves, beheaded the flowers. She quelled the waves, parched the springs, bent the crops with sadness till they dropped into dust. She stopped the insects’ work and stilled their songs. Winged creatures walked; wingless ones waited, breathless and motionless, for their own surcease or an end to their goddess’s woe. She enervated the animals, who lay panting in fields and woods, too weak to move or eat or mate. She inquired of every being, plant, animal, rock, or rill. Unanswered, she shredded the sky and harrowed the earth.

The girl unfound, the goddess withdrew to a ruined temple. The wreck, sacred to an outworn mystery cult, bestrode a cliff. At the back of a tiled courtyard within its cracked walls, stood an immense basalt altar, the work of Titans, or perhaps Northern Giants. Its massive carved-obsidian door opened onto a stone staircase, which descended to a subterranean chamber.

Into this lair at the world’s core, the harvest goddess retreated, restless on a marble bed, wordless in darkness and tears. Twice daily she emerged, gazed upon the useless world, and returned to the cavern’s deep shadows. The musk of her mourning covered the earth. The sun, meanwhile, without her supervision, burned away each day’s clouds and hid itself in a cloak of blood.

Her subjects sought her, of course, almost as devotedly as she sought her daughter. And more desperately. They missed their queen; she was, after all, their mother, too. Crouched silently at the door of her refuge, they offered to share her sorrow, a token of fealty she accepted.

She tossed and turned on her rocky couch, groaning. Her grief for her beautiful child grayed and gaunted her. Tears ran off her rocky resting-place, flowed and fell down the cliff to nourish a sudden forest, loyal trees and shrubs that arose overnight, thirsty for earth’s sole shower. They grew, they lived, indeed, but having drunk of the goddess’s grief, they could never fruit or flower.

* * *

People, meanwhile, continued in their heedless way, neither wise as beasts nor patient as plants. Lonely but selfish, hungry and weak, caught in their own petty whims, they went on getting and spending, stealing and robbing, hurting, and hating. Their debt to the harvest goddess was great but unacknowledged. Numb to awe, too proud to kneel, they seized her gifts without respect or gratitude. Depending on her but disbelieving it, they consumed her bounty but remained blind to her beauty.

Unmistakable signs awoke her human subjects to the green world’s distress. They learned of this as they always learn the little they ever do learn. Because it affected them. The cows ran dry. The growing grain faded and fell. The rain came no more.

The men plowed on, planting parched and broken earth, cursing it and all creation. Few of them thought to open themselves to the harrowed world’s wishes or to throw themselves into the goddess’s lap like the children of hers they were, though spoiled and stubborn children. They drank when the moon rose.

The women wept meanwhile, for they watched the children starve. They berated the men, who foolishly urged themselves forward in their scarring, wasteful work. The soil cracked, the furrows crumbled, the new shoots failed.

The women watched and wailed. “Oh, we have done something to anger her. What was her name again? The one with the horn full of good things, fruit and flowers and grain. The one to whom we used to give the boy—or was it a girl?— every spring.”

The men plowed past the women’s plaints. Then, tired of plow and plaint, they dropped their tools in the fields and left for the towns to carouse. Eventually the women, too, silenced because unheard, careless because care was useless, walked away, leaving small unburied corpses, windswept houses, sandy barren fields.

After, like the men, distraction, evasion. Consolation for ruin inconsolable. Forbidden entertainments and strange pleasures. As throughout human history, blood and death alone merited attention. The men would have made war, the ultimate distraction and consolation, but they were too weak and hungry to prosecute such plans.

The memory of true abundance faded, too painful to sustain. People sought ignorance instead. Wore out the body to anesthetize the mind. Sat down to eat, gluttonously consumed their meager stores, and rose up to play. Squandered themselves in profligacy, drunken slumbers, orgies, the varied varieties of sowing in drought that reaped only wind.

* * *

Disturbed by their clamor and complaint, so loud it reached her in her cave at the heart of the earth, the goddess concluded they were a mistake. The sickness of the land failed to drive them to seek and propitiate her, the only consolation she would have valued, an effort which might indeed have moved her to mitigation. Instead, it reminded them undeniably that they were temporary.

Knowledge that warped and enraged them. Made them even more wolfish and wasteful. Shallow yet unfillable. Incurably poor because greedy and unsatisfied. They grew tired, they grew old, they grew dead. How rarely they grew wise or good! Before, she had called forth white winds and rain to wash away their coarse profane chatter, but no longer. In disowning her, they disowned themselves. The goddess closed her ears against them, groaned once more, and turned her face to the cold dank cave wall.

* * *

Two moon cycles after the goddess’s daughter ate the seeds of love, following which growth of all kinds had fallen off severely, a headless naked creature with a woman’s breasts, big-bellied and bigger-bottomed, lost herself in the woods beneath the cliffside cave. This strange being, a minor Mediterranean deity seeking herbs and edibles, wandered about, grunting and muttering, scratched by brambles and plucking stickle-burrs out of her bushy bush. Perhaps she didn’t know she didn’t belong there. Didn’t realize that these verdant inconveniences were guardians of a sacred space.

The wanderer discovered the last wild blackberry on earth wizening on the vine, and popped it into herself. In those old days, a wild blackberry bore within it thorns as well as seeds, thorns that rasped her unexpectedly in certain tender places. “Great shittin’ sea-cows!” she exclaimed, in a voice hoarse but penetrating. In darkness high above, the goddess opened one eye.

The creature crashed through the bushes, calling on all the dusty crossroads gods of ancient Asia Minor—they were her cousins, some incestuously so—to witness her struggle, and even more, to protect her, if they would but bestir their lazy carcasses. As if in answer, the blackberry bramble snaked around her ankle and took her down.

She lay still a long moment, her nut-brown nipples pressed into the cool loam, a most agreeable sensation even though it left her blind. Her round and burnished belly rested comfortably on a tender tuft of new grass, and her lavishly-proportioned other portions protruded into the air, caressed, again agreeably, by a playing breeze. A stentorian series of imprecations broke the pastoral peace, issuing indeed from her old unspeakable and ascending on the breeze to the invisible portal high above. The goddess opened the other eye.

“By the fecund fur of Ishtar, you indolent milk-faced layabouts!” the creature exclaimed. “Raise me!” The goddess slid from her unyielding divan, crept to the mouth of the cave, and peered out, careful to remain unseen. Far below but quite distinct to the sharp-eyed goddess despite the scarlet-shadowed sun, was some sort of living being, an unknown or at least uncommon sort, in that it was clearly speaking, and speaking clearly, without posessing a head. Through its nether mouth, apparently, although the goddess couldn’t quite make out the details.

Curious, she emerged from the cave and picked her way down the gorge. The cliffside’s ancient rock-hewn steps, carved, like those of the temple, by the cult’s votaries, were wider and easier than they looked. Just as the goddess reached the wild and tearstained woods, the creature bounced upright out of the briars. She bobbed into the air like those green glass balls fishermen attach to their nets and toss seaward to mark where they’ve cast. “Thank you, boys,” the headless one said, but the harvest goddess neither saw nor heard anyone else.

“Oh, eh, ah.” The being returned to earth. It clicked its callused bare heels, squared its shoulders, and brought its breasts to attention, so to speak. “My respects to you, madame. Do I not have the honor of the harvest’s lovely presence?”

The goddess nodded. Suddenly she felt too weary to speak.

“Lookin’ peaked.” The creature fished around inside itself somewhere, the goddess could hardly imagine where, and produced a coarsely-woven linen bag. “Simples! They be just the thing. A little jasmine tea with sassafras shreds to give it a kick. Brace ya right up. Won’t take long. Brought m’own water.” It produced a bulging brown-and-white goatskin, again from parts unknown. “Seems to be a drought.”

It built a fire instantaneously. Kindling seemed to leap to hand and jump to flame. Two earthenware cups emerged from the linen bag, one grass-green, the other deepwater blue. The headless one uncorked the goatskin, aimed, and squirted each cup brimful, losing not a drop. It settled the cups directly on the fire and sprinkled upon them musty herbs from a stone flagon.

The creature soon plucked the cups barehanded off the flames. It offered the goddess the green one, cool to the touch though the brew it held simmered visibly. “Drink!” It sat abruptly, scandalously cross-legged at the goddess’s feet, and poured tea into its lower self as if to demonstrate. It seemed to be slurping.

The goddess averted her gaze from the spectacle, sipping tentatively at her own tea for something to do. The potion was irresistible, however; she drained it in a single ungoddesslike draught, as if to indulge in the uncouth ways of the very odd being who’d brewed it. Braced up, as promised, the goddess abandoned ceremony and seated herself across from the creature, still not sure where to look.

“Simples is the thing.” It drained its own cup with satisfaction. “Nothin’ fixes ya up like herbs and roots. Oh, well, I got some eats, too; here.” It rummaged again in the linen bag. “Sweet figs a few days gone, down back o’ Smyrna (ya gotta watch out for the farmers, y’know, but I’m still pretty spry). I come up around here, outta my usual turf, but my geese got tired o’ luggin’ me, went back ta rest near Ephesus. ‘Lemme down early, then,’ I says to Oriel, the lead gander, an’ quit honkin’ about how overworked y’are. G’wan back, rest yaselves. I c’n still get around much as I need to afoot, thank Ahuramazda.’ Let me down easy they did, but their feathers was mighty dusty—no rain, y’know, madame,” the creature said pointedly. “Slim pickin’s till I got here, nowt but frogswort an’ a little orange-yellow slime-mold (that goes good with fingernail-parings in a love-charm, y’know, madame).

“So I was parched, I was. River was down, a wet thread in a mud-flat, bitter as pee, but at least sorta damp. Drank, got up, an’ stumbled acrost this.” The headless one reached into the bag to retrieve a bright-yellow length of silk.

“Hers!” The goddess reached toward it.

“Yeah, I figgered. Stumbled right acrost it like I just done now.” The being handed over the garment. “My nipples is gettin’ short-sighted, I reckon. You heard o’ people with eyes in back of their heads. But I got mine right up front here. ’Cept they droop now, ’stead o’ swingin’ like they use ta. Oh, I was a looker once, b’lieve me, in both senses o’ the word.” The creature pirouetted like a child, the breasts moving with elephantine grace in accompaniment. “But I don’t see far an’ wide like in them days no more.”

The goddess gaped, curious in spite of herself, distracted from her turmoil for a brief moment. “You see through your nipples?”

“Well, yeah, madame. Ain’t got no eyes. Ya noticed that, ain’t ya?”

“How do you hear, then?”

“Belly-button.” The creature came so close the goddess could touch it, had she wished. Clean smells of lavender and rosemary wafted forth. “Go ’head, go on. Whisper something.”

The goddess, on the edge of amusement, whispered a question.

“Aw, madame, what a question! I shit with that one, of course. What do you do with yours?” The headless creature guffawed, a huge sound that careened from the cliff to the forest and back again. “Here I am, complainin’ about my nipples gettin’ nearsighted. But you, madame, you got troubles way beyond that. They’re weighin’ ya down, too. You look like you got a few too many growin’ seasons on ya, if ya don’t mind my sayin’.”

“Where did you find this?” The pale goddess inspected the creature’s find, a narrow delicately-embroidered belt, her own needlework, last winter’s pastime.

“Hangin’ on a leafless tree, the one I stumbled against when I finished drinkin’.”

The goddess spread the garment across her knees, She stared at her companion. “Where is she?”

“Down there, I heard.” The headless one jerked a thumb toward the ground.

“Ah, yes. Of course. He would.” Death was well known to her. They worked together sometimes, in fact. They were relatives, too, of course. Grew up together. The goddess frowned, thinking about him. That he would. What he would.

“Who are you?” The goddess stared at the creature.

“Oh, you know me. You an’ I are far cousins, the removed kind, y’know. Asia Minor; some of us stayed when everyone else colonized the Aegean. My people liked the beach, too, but we went to the Mediterranean. Baubo, they use ta call me. I’m up-to-date, though, I am: I took a futuristic name. You can just call me Old Vee.

“We’ve met before, Cuz. Remember those initiation ceremonies years ago at the shrine of Cybele? Those geometric scarifications?” The creature took the goddess’s hand in its own soft, warm ones. “Lessee the inside o’ yer arm, madame. Aha. Mm-hm. Look here: jus’ like mine. Circle in triangle in square in circle.

“You was in line behind me, but I don’t wonder ya didn’t recognize me. I wore a robe in them days, an’ a wrap besides—couldn’t bear my own beauty yet.” The creature giggled. “Too weak ta face my own power. I had ta cover myself from myself in those days; I had a lot ta learn.

“We met, all right. I had the tambourine an’ you got the lyre. My, oh, my—you played like a goddess, madame.” Old Vee laughed. “They give me the tambourine ’cause I sang loud but not pretty. Not always disciplined or ladylike. Nor dainty, not at all.” Another chuckle from deep inside. “Didn’t always pick noble well-mannered partners for the dance. Oh, but those I picked stood up to me, madame. They was hot ones, wasn’t they, now? Remember? We was fourteen the night they made them scars and gave us them ephebes. I talked ya into tradin’, an’ that boy an’ me, we did the dance all night. Set a record, we did. They made him a honorary satyr.

“An’ me, well, that hot boy I traded you for, he was Love himself an’ that night was my interview. Tutored me fer my present position, so ta speak.” Old Vee saluted. “Groomed me young to be his helper out in the country. Ain’t he a relative a yours, too?” The goddess nodded. She stared at the silken sash. She smoothed it repeatedly.

“That right, madame? Ya really didn’t know where yer daughter’d got to? So distracted by Egyptian corn-borers or Babylonian squash-beetles that ya couldn’t figger out it was one a yer brothers or t’other? Knowin’ them two, I bet they made a bet. Or maybe Love was jist feelin’ his oats.”

The harvest goddess hung her head and sniffled, a most un-divine sound. She gathered the hem of her gorgeous but damp and wrinkled robe, white silk shot through with a pattern of sheaves in gold thread, and blew her nose into it.

“Oh, c’mon, madame. Ya gotta snap out of it! She’s gone where the seed goes that you bring to light, to fruit, she’s gone deep, deeper even than she was inside ya, deeper even than you go into the ground. Gone where the fallen leaf goes, the shed skin, the spent flower, the rain.”

The goddess still couldn’t get past the wrong angle of the creature’s hoarse and penetrating voice, issuing from the ground, it almost seemed. She wondered if its lips moved. “Your problem is, all ya understand is life and goodness. Ya don’t know nothin’ about death and darkness. Ya didn’ warn her, and now ya can’t find her ’cause she’s gone into a world ya don’t know nothin’ about.

“Ya haven’t interested yaself in that part, and why should ya? It’s filthy, full of muck and ferment and fungus, decay and dissolution. Disgustin’, too: putrefyin’, melted, moldy, rotten. But it’s half yer domain, madame, the hidden half you have to have. Without which you can’t work, can’t plant or harvest or gleam or glean. You better do some research, mama. You better find a map or talk to somebody’s been there, somebody knows the lay of the land.

“And what’s the big deal, anyhow? He loves her. He married her, didn’t he? Unlike all these other pricks who come down in a shower of gold or chase us all over the woods and leave us with babies they never claim. Ya know what I’m talkin’ about, don’t ya, madame? Huh?” The goddess nodded miserably, her face in her hands. She knew, all right.

“She’s a woman now, Mama, for good or bad, outta your protection even if she’d married a nice little pastoral god an’ spent her life shearin’ sheep and boilin’ mutton and wipin’ the smudged beautiful faces of the curly-haired little sheep-shearin’ godlings he gave her. She’d be outta your reach no matter what, once she did the deed. Remember? Just like feeling swamps knowing, fucking beats thinking every time.”

The goddess moaned. “She would have been out of my reach, but not out of my sight. I miss her so.”

“Ya wouldn’t wanna see her there anyhow. Which is in his hot bed, as you also well know. She’s gotta get dressed an’ get up here an’ see you. Ya can’t go down there, you know that. It’d kill ya, and therefore kill the rest of us. Think of yer responsibilities, madame. Ya gotta go have a chin-wag with her father.” The goddess’s brooding had yielded this same conclusion, and somehow the creature knew it. “That’s the spirit, madame. Resolve yaself upon the journey; the omens in Scythia as I passed through were all to the good.

“Ya better get some lightness in yer demeanor, however. As you’ll recall, brightness and vitality captivate him.” The goddess gestured as if to reply, but the other continued. “You ain’t in no shape to revive the green world, madame. You gotta fix yaself up. Crush some lemon-balm leaves in yer bath, anoint yaself in an incendiary fragrance, slip into that new white chiffon with the gold-threaded Doric motif at collar and hem.

“And—” the creature spoke firmly, as if giving an order—“Look on the bright side, madame. Think positive.”

Surely Old Vee hadn’t ordered a goddess about, that would have been presumptuous. Or surely she had. Although they are indeed not-so-distant cousins, as the creature so boldly claimed, Old Vee possesses certain powers even stronger and more mysterious than those of the harvest goddess.

“Here, madame, lemme help ya.” The creature seized the goddess’s gray veil and playfully wrapped it around her own oddly-shaped self. “You still wonder about me, do you not? Wish to see for yaself what upon yaself you barely see?” Old Vee laughed, shuffled into a complicated dance-step with something beyond grace, and faced away from the goddess. Old Vee bent double and removed the veil to give the goddess a good long look. “See? They do move when I speak.”

The astonished goddess burst into laughter, belly-laughs very like the creature’s own, coming from the same place, the depths, the fecund and mysterious gates of abundance and pleasure. “Look, listen, and obey, my dear madame.” Old Vee laughed at the figure she cut; she knew how to laugh at herself, of course.

Some minutes later, when they’d caught their breaths, the headless one returned the goddess’s veil. “Now surely ya gonna get up there an’ charm him. Now that ya laughed, he’ll hear the lightness in your request and the passion in your speech. The Scythian entrails foretell success; all Abyssinia burns incense an’ cloves to prepare yer way there. Remember yer holy laughter, madame. By this ya can see yer child.”

* * *

The girl’s father, the royal and divine emperor of all, resided, like Death, in a distant land, a vast day’s journey from the cave at the core of the earth. The goddess sojourned there once, eons past, hijacked like her daughter, but toward light rather than darkness. Either is terrifying to those who live between. The emperor’s long-ago kiss put the goddess, too, in a dream, though she saw all and forgets nothing, their beating hearts, his burning touch, her fiery astonishing rejoinder. Their beauty in conjunction.

Months after, the girl-child emerged, breaking anew her mother’s body, no pleasure this time, instead a painful joy. The waters broke, the goddess roared and shouted as the child burst forth. Flowers sprang into bloom everywhere, the earth’s delicate extravagant congratulations.

The goddess remembers how to go, the way up is much like the way down. Shining, she brushes past the emperor’s guardians and attendants; they fall away, making obeisance as they recognize her. She smiles and curtseys to the emperor’s jealous wife (at least Death is a bachelor). She stops to salute her kin. Love is one, Light another, Change, the emperor’s messenger and magician, another still. She jests with him and makes him laugh. Her mirth and her bright brow cause Change to buckle on his fast shoes. He understands why she came.

He knows before the emperor does that the emperor will grant her wish. Above as well as below, laughter is the music of enchantment, an enchantment that so easily ensnares the emperor, lonely on an unquiet throne beside that powerful sour wife. Change throws on his cape, preparing to descend and deliver the emperor’s command to the dark world beneath the world between.

* * *

You know the rest. If you’ve eaten a tangy fall apple or quaffed the rough red from that gurgling jug in your saddle-bag, if you’ve grabbed a hot fistful of fresh bread or let ripe goat-cheese melt on your tongue and release its perfume, you know what happened next and how the tale turned out: change and growth, decay and return.

If not, you poor soul, here’s the news: the girl returned to her mother’s place for six sweet months each year. The world came back to life, and to death: they’re married and inseparable. Here’s the non-news: the humans learned nothing, but the gods looked after them anyway.

Yet, as you must have noticed, my yarn stints one answer. Against the rules of church and state, my tale avers that Death, like us, can be tempted. That life wants to yield. That earth, too, is mortal. That the ever-returning harvest could fail us. That all this unfolds as it must, that every tangled tale, including mine, reveals a larger plan and power speaking through it.

We could say that the Fates meddled, sending a minor but obstreperous goddess, life-giving and unthreatening, to nudge the harvest back to work. That during the goddess’s mourning, because people dared strike no sparks in their tindery groves and fields, neither sacrifice nor incense delighted Those Above. That the stench of carrion, spoiled crops, and corpses wafted upward, rather than the perfume of roast meats, sage, and myrrh that keeps the gods in temper and distracts them from involvement in human affairs.

That three heads are better than one, even among the divine. The Fates had a larger plan, one that eased the harvest goddess’s burden. Even before her daughter’s abduction, she was overworked. She ruled, which meant managed, the two fertile seasons. Hers to oversee, beset by weather, pests, laziness, territorial disputes, bad seed, bad farmers, bad plans, the world’s spring planting and fall reaping.

The Fates invented two more seasons. One, to follow sprouting spring, called summer, days of languid burgeoning, of heat and light, desire and abundance. One more to close gathered fall, called winter, a cool and fallow time of incubation and repose. The harvest goddess wouldn’t welcome this plan. But she would welcome her daughter.

The girl, six pomegranate seeds and one ghostly lover to the bad (leaving aside the issue of subterranean congress with her uncle), herself immured underground so like a seed, would answer the Fates’ summons, rise to rule the new seasons, pleasing her mother but maintaining her own ménage with ardor and rigor.

I told you what happened, as promised. Warmed by your fire, full-bellied with your food, and loquacious from your wine, I told you how and when and who, and one thing more. Rather than disdaining this lone wanderer, your generous good-fellowship subsumed me, the stranger, into your tribe. Tempted me, with my high, lonely knowledge, to unriddle what I never can, to judge as I never may.

Now must I take my leave. Now must you take your own turn in the space I leave open. Explain for what cause each tale unfolds the buried. For what cause love and death, dark and light, drought and famine, flood and surfeit, move you. For what cause life itself enters and spins your own tales thiswise and not otherwise, weaving and embroidering the words into your hearts until the cups fall from your hands, the fire sinks, and you tumble into dreams.

___________________________________________________________

D

Deirdra McAfee’s fiction has appeared in

Shenandoah,

Tupelo Quarterly,

The Georgia Review,

Willow Springs,

The Diagram, and others. She co-edited and contributed to the literary anthology,

Lock & Load: Armed Fiction (University of New Mexico Press, 2017).