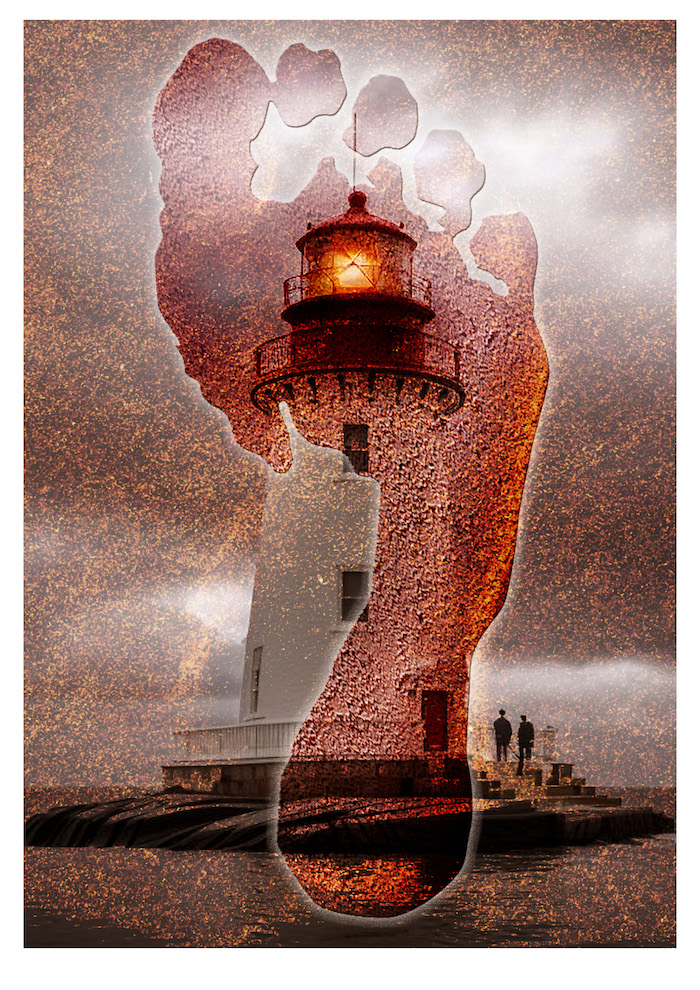

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, Fall 2024

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY CAITLIN A. QUINN

On the stretch of beach below the lighthouse, there had been a footprint. The outline of a bare left foot in the sand, not much larger than Anna’s hand. She had seen it that morning, before the sun was up, but when she crossed the beach later to get to the dock, where Ciarán waited in his boat, it was gone.

“There’s a storm coming,” Ciarán said, pointing to the swells of darkness gathering to the west.

“Good thing this island’s got a lighthouse.”

Anna knew she shouldn’t give cheek, but the old boatman’s condescension was tiresome, starting from the first moment she’d met him, when he had ferried her to this remote, rocky isle, so she could take over the lighthouse’s caretaking duties. She remembered the look of challenge in his rheumy eyes when he had asked, “What does a woman want with a place like this? Wandering on a rock, bound to a light, with the nearest soul miles across to the east, and nothing on the other side but the western reaches?”

How long ago had that been? Weeks? Months? It was hard to keep track of time here, one day seeping, thick as treacle, into the next.

And there was the other question he had asked that first day, as he started the boat’s engine, readying to leave—the same question he asked every time he came: “Are you ready to go back?”

Her answer was always “no.” She didn’t want to be anywhere but here, where the lighthouse’s bright gold beacon comforted, granting respite from nightmares in which different lights of another color bore down upon her: the cold burn of the ambulance’s blue flashers and the numbing shroud they cast over Dublin’s wet streets.

She’d spent five years behind that ambulance steering wheel. Racing to heart attacks in Drumcondra. Dodging taxis to reach stabbing victims in Parnell Square. As she drove, she imagined the wheel was Death’s arms pinioned by her tense fingers. That her foot crushed Death’s windpipe underneath the gas pedal. Until the night Death had taken revenge, casting itself first in the form of the pint her boyfriend, Barry, had ordered for her in the pub an hour before she was due on shift, and second in the Audi’s careening sleekness.

The footprint. It had been there on the beach that morning. Anna was sure of it.

“Could there be anyone else on the island besides me?”

Ciarán shook his head. “I’m the only one can navigate these waters, and I’ve brought none here but you.”

“But could they have swum out from the mainland?”

“Anyone going into that water wouldn’t make it twenty feet before it finished them.” Ciarán scratched at grey chin stubble. Anna noted that his usual morose temperament seemed tinged with impatience today. He glanced up at the dark clouds hanging over the western sky then gave Anna a look she didn’t like. Different from his usual deprecating frown. This one smacked of pity. “The storm will be bad.” Then: “Are you ready to go back?”

Something in his voice unnerved Anna, and she felt her defenses loosen, like a spool of fishing line unwinding. “I’m all right here.”

The old boatman shrugged. “I’m off then.”

After Ciarán left, Anna returned to the beach, to where she had seen the footprint. She searched again, but no trace of it remained. The inside of her mouth felt chalky, and it was hard to swallow. She stared at the darkening sky. As she watched, a bolt of lightning, its edges flashing blue, sparked inside a storm cloud.

She found another footprint. This one in the mud outside the light-keeper’s cottage. Anna saw it when she went outside in the gloaming to turn her face up to the lighthouse lantern’s soothing glow.

The leaden clouds had reached the island. The air they brought tingled Anna’s forearms, pebbling her flesh. There was a scent—heavy, metallic—as though the sky were breathing through a mouthful of pennies.

“I know you’re there!” she called out. “I see your footprint!”

Anna threw on a yellow rain slicker and walked around the side of the cottage. She started down the steep path to the beach but was stopped by a brilliant flash of lightning that left a jagged blue line imprinted behind her eyes. Her throat felt tight and ached.

The rain came down, unassailable and insistent. It slapped against the hood and shoulders of the slicker and blurred Anna’s vision as though it were a veil of gauze. She’d go back inside the cottage. If someone were out here, they would seek its shelter.

Anna dried her hair and wrapped herself in a blanket. She added wood to the stove and sat down on the couch, listening for any tentative knock on the cottage door, any creak of its hinges.

Flames rose behind the stove’s glass, and Anna sat before them, shivering, unable to get warm. She thought about eating something but couldn’t decide if she were hungry. Had she eaten anything today? Was there even any food in the cottage? She couldn’t recall. The rhythmic, golden crawl of the lighthouse beacon across the cottage floor lulled her to sleep.

When Anna opened her eyes, the beacon’s reaching light was gone, replaced by the brutal gash of steel that had been the Audi. Had she not seen the car in time? Had her reflexes not been quick enough to avoid hitting it?

Through ears still ringing from the crush of glass and metal, she heard Michael, the AP, moan from the passenger seat beside her, his face bloodied.

Anna, groggy, her head aching, stared at the Audi through the ambulance’s broken windscreen. She couldn’t see anyone stirring inside the car.

Then a small boy looked out from its back window.

Anna fought to unbuckle her seatbelt. That’s when she heard the whoosh of flames.

The Audi’s crumpled bonnet was on fire. Smoke filled the car’s interior. The boy pounded on the window.

Frantic, Anna pushed at the ambulance door, but it wouldn’t open. It was only then she realized the vehicle was lying on its side.

She kicked a hole in the windscreen, clawed her way through it, glass-bitten hands slick with blood. Tumbled to the street. Stood. Staggered forward on legs of dead weight.

Anna fell against the Audi’s backseat door, tugged at its handle. The door wouldn’t open. The boy’s face was no longer in the window. Anna pulled harder. The door flew wide.

Smoke billowed out of the car and into Anna’s face, stinging her eyes. She reached blindly inside the backseat for the boy. Her hand fell on something. A foot! She pulled and something came off in her hand. A small running shoe. She threw it away and reached back in. Her fingers closed on fabric. A trouser leg.

Anna dragged the boy from the car, cradled him against her chest as she hurried away. She laid him on the sidewalk. Looked at his blackened, still face. Lifted a lid to reveal an iris of dizzying blue. The blue found along the edge of a lightning bolt.

She felt his throat for a pulse. Nothing. She put her hands on his chest, counted out thirty compressions. Checked his pulse again. Nothing.

Anna put her mouth over his, pushed two breaths of air into his lungs. Put her head to his chest. Heard nothing.

Went back to compressions. Then breaths. Over and over, until Michael, hovering unsteadily above her, his voice ragged, pronounced, “He’s gone.”

Anna cried out.

The boy was still there, but now he was standing in the cottage, alight in the beacon’s glow. His face was streaked with black residue. His eyes were blue stars. His clothes stank of smoke. His left foot was bare.

Anna sat forward on the couch. “I’m sorry,” she said, and started to cry. “I had a drink. That pint, before I—”

“It’s not your fault,” the boy said. “Mam was on her phone, fighting with Da. She didn’t see the light change.”

Something flooded Anna’s chest. She sucked in a breath, tasted smoke and bile in her throat. Every part of her shook.

“You need to go back,” he said.

“To Dublin?”

The boy looked past Anna, out the window, toward the lighthouse.

“It’s fading.”

Anna shook her head, but then she saw it: the beacon’s pulsing gold had dwindled to a sallow yellow. “I don’t understand. I tried so hard.”

“You took pills,” the boy said. “Because you felt bad. About me. But you shouldn’t.” The boy turned his head toward the open door of the cottage behind him. “He’s here to take you back. Though he doesn’t like to go that way.”

The boy’s hand was cold in Anna’s as he led her to the dock, where Ciarán was waiting in his boat, his face hidden beneath the dark hood of a rain slicker. She squinted through the slanting rain at the beacon’s slowing, waning pulse of light.

“I’m ready to go back,” she said.

The old boatman said nothing, just started the motor while the boy untied the mooring lines.

The storm was subsiding, its turbulence having faded to a soft mizzle. Anna felt a warmth in her limbs she had forgotten to miss. And the boy on the dock grew smaller, and the lighthouse beacon behind him became brighter, as the boat made its way out to sea, across the western reaches.

___________________________________________________________

Caitlin A. Quinn’s short fiction has appeared or is upcoming in Electric Spec, Tales To Terrify, Identity Theory, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and Fiction On The Web, among others. She is a member of the Horror Writers Association and lives in Northern California with her partner and two badly behaved Airedale terriers. Website: caitlinaquinnwriter.com.

Caitlin A. Quinn’s short fiction has appeared or is upcoming in Electric Spec, Tales To Terrify, Identity Theory, The Fairy Tale Magazine, and Fiction On The Web, among others. She is a member of the Horror Writers Association and lives in Northern California with her partner and two badly behaved Airedale terriers. Website: caitlinaquinnwriter.com.