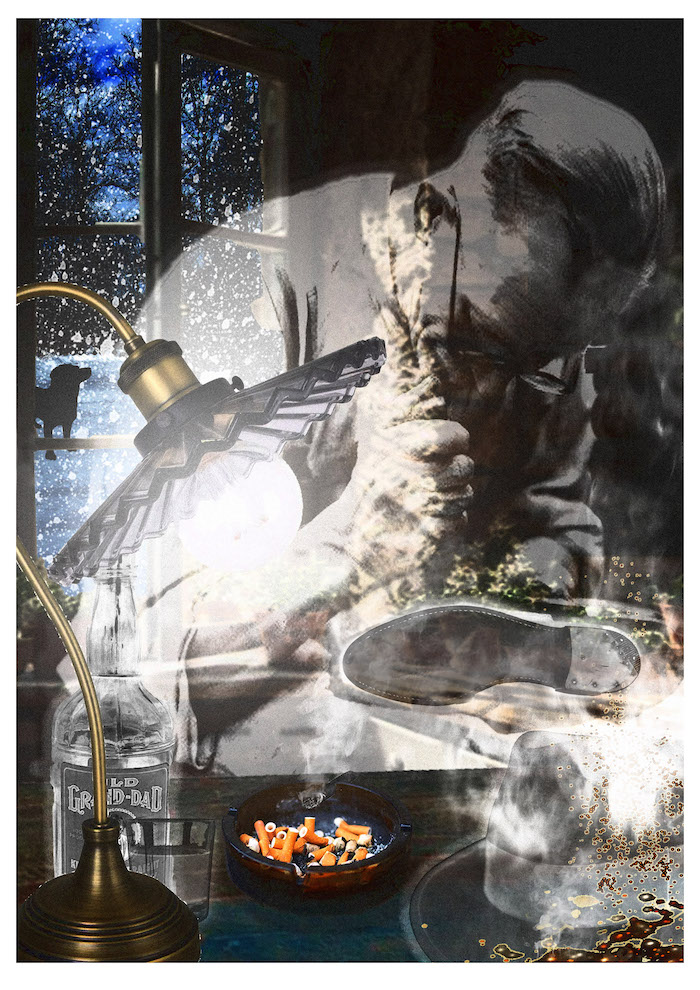

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, Fall 2023

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY JOSEPH BATHANTI

My dead grandfather was in the house.

He had pried open his tomb at Mount Carmel, paced, hands clasped behind his back, down Cemetery Hill, to Lincoln Avenue, made a right on Meadow Street, doffed his fedora at Our Lady’s—where he’d taken the sacrament of Holy Matrimony, where my mother and her brothers had been baptized, where he had reposed in his closed casket during his Requiem—and paused there at the church an instant before crossing Meadow Street Bridge—from which suicidal East Liberty legends occasionally leapt—over the abyss of Basa La Vallone to our duplex on Saint Marie Street and let himself in through the back door.

In the bathroom, my mother, scrubbed with fury. Dove on the rag again and again until her face, diaphanous in the inquisition of the sputtering, naked bulb, screwed into the wall above the bathroom mirror, gleamed like a skull: suspiciously high cheekbones, exquisite buckeye-brown eyes. A fiery eruptive complexion as a girl—doctored by her gypsy mother with pumice and witch hazel—had left her face porous, punctured. Pregnancy with me had leached calcium—her teeth, silvery shale—yet she desired another baby that refused to root, as if cursed, in her womb.

Her hooked nose. Aquiline. Roman. Those were pretty words for it. Rita can smoke a pack of cigarettes in the shower and never get one wet—the joke her brothers, my sadistic uncles, fell apart laughing over. Piss on them. Piss on everyone. She wasn’t so bad. She could certainly hold her own with those washed-out housewife hags hunching down the avenue with their Giant Eagle shopping bags. She permitted herself an instant to gaze at her likeness. She wished she were prettier—her mother, my grandmother, had been exotically beautiful—but piss on that too. Piss on everything. Pretty is as pretty does, and she didn’t do poor-mouth, wheedling pretty, wouldn’t-say-shit-if-you-had-a-mouthful pretty. She was pretty enough to tell any man on earth he could kiss her ass.

At that moment, as she looked in the mirror, she knew my grandfather was in the house: her father, Federico, Fred the shoemaker, my grandfather immolated when his shop took fire in 1942, when she was nine years old. That son of a bitch, after whom she had named me, her only child, that son of a bitch she imagined she had murdered by somehow causing the fire, even willing it.

How the memory construes memory has never been determined, and my mother, since 1942, nine years old, had settled on a rendition—perhaps true, perhaps not—of what might have happened that afternoon on Station Street. It became her world, the cruel world. It sat upon her: a planet of grief and regret, revoltingly sentimental, authored so exquisitely that she had forgotten what had really happened—as we all must, in our fictions, to forge ahead in daily toil. Thus she simply did not know how to stop blaming herself for her father’s death, and for every calamity that transpired in her orbit.

She swept into a knot her crown kinky, dyed blonde hair—taut black roots clutching her scalp—and tied it off with a claw-clip, whipped out a Chesterfield, lit it with her Zippo and puffed it held between her lips, as she caked Pond’s over her faccia brutta. The bulb fizzed, then expired with a flash, leaving a stench of fried wire and rubber. Bulbs were always blowing. The plumbing was the same, patched and taped, the fetid reek of rust, bealing antique fixtures. The landlord was an animale.

She stepped into the hall, where a nightlight burned, and stood between the two bedrooms. My dad snored unmercifully, something that typically infuriated my mother—she frequently threatened to murder him over it—but that night it oddly comforted her. In the glow of the light into the opened room, she made out his draped body, wrist-watched arm dangling over the edge of the bed. Then, like the refrain of her life, came the keen of a freighter loaded with coal, heaving through the crossing, a half-mile off, on Penn Avenue. The furnace kicked in and our entire duplex shuddered.

She buttoned the top button of her white flannel nightgown, stepped to my open bedroom door, and listened prayerfully for my breath. In green flannel pajamas, I lay uncovered, on my back, ankles crossed, arms spraddled, palms up, mouth open. My mother tiptoed in, spun a flame from the Zippo—the sudden odor of Butane—and held it above me. My eyelids fluttered. I moaned. She doused the flame, pulled the bedclothes to my chin, and bent a kiss to my forehead. I had been asleep, dreaming of my grandfather, down in the kitchen. But I woke the moment my mother stepped into the room. A thrumming urgency, near danger, habitually accompanied her; her lips against my forehead crackled with electricity.

She fastened my bedroom door behind her, then the door to her and my father’s bedroom, and walked barefoot down the stairs to the first floor, assaulted by the stench of char and smoldering, leather, and slightly sweet, turned earth. I smelled it too. I lay there another moment, then followed her downstairs and remained, in the dark, on the landing that split our dining room and living room.

At the kitchen table, in the halation of a gold cobbler’s lamp, slouched my grandfather: cobbler’s apron over a white shirt and necktie, head bent, strands of white hair, escaped from pomade, fallen over his brow, the bottle of Old Granddad from under the sink next to a half-filled glass. A skinny black De Nobili simmered in the astray with a dozen of my parents’ stubbed butts, my mother’s bloody with lipstick. His fedora smoked on the table. He sweated. The air about him sizzled.

On his left hand, he wore a metal palm thimble. With a rosewood knife and lethal copper cobbler needle and thread, he repaired the high white patent-leather go-go boots my mother had left at the door when she’d come home, with my father, from the slush and filth, in the early hours, that same morning, from her job as a hostess at The Suicide King. Between his lips spiked half a dozen brass clinching nails.

At my grandfather’s knee sat our lost dog, Fred—a year wandered gone—named after my grandfather, as was I. My mother, as overcome at the sight of Fred as of her father, moved instantly toward the dog. But he cowered and sidled against my grandfather. Clearly hurt, a little pissed, she withdrew a step, and determined not to cry. Since he’d disappeared, Fred had aged seven, as dogs must, in a lone year. Grifting back to the streets, he’d grown a second-hand ratty thrift coat, and gone gray at his muzzle. He’d been in fights. He looked worse than he had the nocturnal snow-blind morning my parents discovered him outside Foxx’s Grille, put him up front with them in the Impala, drove home and woke me with the crazy proclamation that we had a new dog, and his name was Fred.

He’d been about two years old then, fourteen in dog years. About what you’d expect of an abandoned, starved, scared fourteen-year-old left to the streets of East Liberty in 1968. Pack mutt. Low self-esteem. But not without honor. He needed a bath, a doctor, a bed, good food, and my mother’s pathological adoration, which Fred returned with equal pathology. He slept in my parents’ bed, which my father tolerated and tried to keep his mouth shut about. Fred had been my companion and confidante. I spent evenings, long nights, with him as we waited for my parents to finally arrive home from their restaurant and bar jobs at the top of Baum Boulevard. I had been fourteen too.

My mother blamed herself not just for the death of her father, but also for the loss of her dog. One night, after a brilliantly destructive episode of The Travis and Rita Show—she had wanted to hurt my father and me; but, more than anyone, herself—she had pigheadedly, belligerently, insisted on taking Fred for a walk at dusk in a vicious snowstorm. She’d suffered a steep hard fall, was knocked witless, and lost her grip on Fred’s leash. We never found him, despite a long, lavishly operatic search in a blizzard.

My mother collapsed at the table across from my grandfather, her dead cigarette still between her fingers.

“Papa,” she uttered.

Federico did not look up at the sound of his daughter’s voice. He placed his tools on the table, stared down at Fred, and petted him. The dog gazed deeply into my grandfather’s eyes, as he had, when he lived with us, so devotedly into my mother’s eyes. As he had gazed into my eyes. He had been in love with my mother, and now he refused to look at her.

There was kindness in my grandfather—evident in the way he did not look up and petted Fred—perhaps too sheepish, as the dead are often when they appear. But the kindness was buried, deep as a dead child, reserved for a dog. My grandfather had borne too much in steerage across the Atlantic from Napoli: hunger, nothing but his satchel of tools, no language in either tongue. Mute. Burning. Then decades of rusted, lock-jawed silence: suit of smoke, pillar of fire, a stony hill in Mount Carmel under a crucifix with his name chiseled into it: Federico Antonio Schiaretta. The dog loved my grandfather, as he had once loved my mother. The way Fred looked at Federico. The way this dog, lost forever, punished my mother.

My grandfather took up his knife and pared a sliver of sole from the shiny boot, drove in the nails, single strikes, set down hammer and knife, and picked up the De Nobili. Its flame puckered and bled. He inhaled, then filled the room with smoke.

“Did I start the fire? Is it my fault?”

My grandfather looked up at my mother, as if about to answer, to reveal what had really happened— because the dead are no longer required to lie. Was my mother, Rita Schiaretta Sweeney, somehow complicit in burning her father at the stake? Had it been merely an accident? The dead, however, when in congress with the living, by writ and lore, are denied rejoinder—the code of silence my grandfather dared not violate. The dead may converse only with birds. So perhaps my grandfather had divulged to a bird on Omega Street—an Italian bird for certain—the true story, chapter and verse, the spliced rickety 18 millimeter of that day in 1942 when his shoemaker shop burned down and killed him. It was in my grandfather’s power to do this: confide the true story to a bird.

My grandfather’s face had not smiled in memory. Surely the dead smile, but my grandfather had forgotten how to arrange his face appropriately. Yet he remembered a smile in a child’s drawing. It could have been Rita’s, his Carita’s—my mother’s name means story—an exquisite orange smile, a colossal slice of cantaloupe. There at the table, that night in our kitchen on Saint Marie Street, my mother peered so imploringly at him. He tried to smile, but his jaw had been chained and padlocked for years and years. Instead, he trembled; smoke rose from him. A sign? Perhaps it meant: No, you are not responsible for the fire, for my death. Was it reassurance in his unblinking perfectly round dark mahogany eyes? Was it something else? Perhaps an indictment: Voi. Carita.

Like reading a Ouija Board, my mother determined that the befuddled grimace on my grandfather’s brilliantly tragic face, along with the melodramatic smoke shrouding the kitchen, exonerated her. My grandfather was old. He was dead. He too craved exoneration. Even the dead, wandering earth, seek absolution from the living. It was time to forgive. Or was it the hour of vendetta? A bird in East Liberty swooped through the sky with the true story.

My grandfather then stood, removed his apron, took up his fedora of embers, placed it on his head, and ground his De Nobili into the ashtray. He drained the glass of Old Granddad, gathered his tools and the lamp, placed them in his canvas satchel with the apron, and stepped into his black overcoat.

My mother stood. Silver tears streamed each cheek and fell upon the table, but she didn’t make a sound. My grandfather handed the repaired boots to her, and with Fred behind him, walked out the back door into the alley.

I had remained on the landing in the dark after following my mother downstairs. The dining room was between us, but I had a clear view into the kitchen. All that’s written here is accurate. My grandfather did indeed appear in our kitchen and recobble my mother’s boots—which have not deteriorated in all these years, despite the untenable treks my mother takes in them—and Fred, our forever lost dog, inexplicably had accompanied him. My mother questioned her father about the fire. All this is true.

However, I am not sure what that declension in my grandfather’s face meant, that miniscule, nearly imperceptible, tic. Perhaps it was merely hesitation. Perhaps, he had short-circuited. Hence the smoke. My mother’s back had been to me. I’m certain she did not know I was there. My grandfather, elegiacally illuminated by the cobbler’s lamp, and I faced each other—his countenance, as he worked, stoically fixed, like a marble bust. It betrayed nothing, but stone. The moments he raised his face from the needle, he raked me with his not unkind eyes. I wanted to go to him. I had been with him before. I wanted to kneel in front of Fred and pet him.

Fred never acknowledged me. I haven’t wanted to say it, but he must have been dead too. He could neither bark nor whimper, nor accept the love of the living. He was my grandfather’s dog now; there’s comfort there. The two Freds. I was used to my grandfather’s death, twelve years before my birth. I am born into the fable of the fire. I knew him only as the mute ghost of an old, well-dressed Italian man with a face of locked stone. But little Fred, the dog? He’d been innocent and had died somewhere along the way—in that year for us, seven for him, since he had been our good boy and slept with my parents—in whatever fashion young dogs of the street lose their precious lives. He had been our good boy.

That’s when I cried, quietly, so my mother wouldn’t hear me—when it hit me that Fred was dead. From the kitchen, my grandfather watched me cry. I watched him watch me—the back of my mother’s head, that big black claw clip sliced across her wiry, tangled yellow hair, in the foreground. He was powerless to come to me. My grandfather stood, the repaired boots in his hands. Then my mother stood and he handed her the boots across the table—whatever the bargain. It did not strike me as absolution. He and Fred then walked out of the kitchen. The smell, the smoke, remained. The De Nobili smoldered. Fred did not look back.

Maybe this is the account I confessed to my mother as she and I sat at the kitchen table after my grandfather had departed. We had been visited by my mother’s dead father, not for the first time, and it was impossible to deny it. I made tea and toast. My mother poured Old Granddad in her tea. She spread marmalade on her buttered toast and dipped it into the tea.

I fetched my grandfather’s De Nobili from the ashtray. I had never smoked before, but I put it to my lips and pulled. It yet had fire.

“Don’t smoke those, Fritzy. They’re too strong, too bitter. Those bitter old Italian people.”

It was too strong, too bitter, a mouthful of slag—my incinerated cobbler grandfather: that frantic shock of white hair, white shirt, necktie, the white Carrera marble of his stubbled locked jaw, the spectacles as he mended. It tasted of my prehistory; it boded of my future. I stabbed it out. Son of a bitch.

My mother lit a Chesterfield and pushed the pack across the table. Without the cobbler’s lamp, the kitchen was dark, yet light enough to see the beautiful packet: Chesterfield in magnificent ornate font, quilled in the scriptorium. It was the most beautiful thing in the kitchen. It fetched the moon looking down on the alley.

“Don’t tell your father,” she said.

My father had never seen my grandfather, dead or alive, but he knew all about the fire—East Liberty lore—and, I’d heard it said, he knew what had really happened.

“Son of a bitch couldn’t spare a word, not a goddam syllable, when he was on earth. Now he’s dead and forbidden to speak. Jesus Christ.” She laughed a tetched Bette Davis laugh. “Do you think the dog’s dead?” she asked.

This was the kind of question my mother typically posed to my father—a test really—because there could only be one answer, and it had to dovetail seamlessly into whatever story to save herself she had already cooked up. You had to say what she desired, period, and it was so easy to trip the wire and behead yourself. The feat of appeasing Rita required, most dramatically, the ability to read her mind. She resented anyone who could not read her mind. My father could not read minds, nor could I, but he was the canniest person I’d ever known when it came to sizing up people, and he never lied, not even to my mother. His thunderous snores, but a few feet above my head, on the other side of the ceiling, comforted me.

My father would have fashioned a way of telling my mother Fred was indeed dead that absolved her. Wise and tender, and she would have listened—reached across the table for his hand. They’d smoke cigarettes and drink VO because out of my father’s mouth had come the very words, in the exact order, pitch and heft, to the syllable, that my mother craved. Her beautiful brown eyes. His beautiful blue. So very happy in the kitchen.

But things could backfire. My father might say precisely what she most loathed hearing, and she shoves the table over. Literally. My mother’s most imaginative performances occurred in the kitchen—at the kitchen table, where I sat smoking with her. Fred was a goner. How could I tell her this?

In the thrall of Rita Sweeney, neither first nor last time, I pinched a Chesterfield from the packet. My mother pried open the hood of the Zippo, fired it up, and lit my first cigarette.

“Fred’s not dead, Mom.” I exhaled my inaugural sentence of smoke.

“I don’t think so either.”

I had to catch a city bus for school in the morning. It was 4:00, the hour when most depart the earth, the hour most babies are born. The transmigration of souls.

I smoked a cigarette with my mother, then I said, “I have to go to school pretty soon.”

“I’m glad it’s you and not me,” she said.

We walked back upstairs to her bedroom. My father, seemingly untroubled by the past, roared peacefully, happily.

“Fritzy,” my mother said. She stood a foot from me. Stunned. In the sway of her father, planning the campaign to find lost Fred, the dog. Glorious in the nightlight, an emissary from elsewhere, her hair a froth of ragged light. “I want you to forget about tonight. Don’t ever think about it again. Promise me. Promise your mother.”

“I promise, Mom,” I said.

She kissed me. “I’m sorry about school tomorrow.”

She opened the door to the bedroom. My father was a jacked-up Malibu in a Negley Run drag race.

“Jesus Christ, Travis,” said my mother, loud enough. “You could wake the dead.”

My father came to, took us in with shock, then back under, revving it up.

“Good night,” I said.

“Wait until I’m in bed, Fritzy.”

She put on her sleep mask, then got into bed with my father.

In succeeding years, my mother would tell the story that a robin approached her one bright spring Sunday, not long after my grandfather’s visit. She’d risen early afternoon, following a long night at the King, then a couple hours with my dad at a speakeasy in East Liberty, the Perry Social Club. She had walked into the backyard in a robe, to smoke a Chesterfield, and this very Italian robin recounted the true story with which her father—whose sole confidantes were birds—had entrusted it. The bird’s story exonerated her. A tale no more outlandish than having her immolated cobbler father return from the dead to fix her go-go boots—which I happen to know is the unflinching truth. I swear to God.

I crossed the hall to my bed. Home room at Saint Sebastian’s in three and a half hours.

Joseph Bathanti is the former North Carolina Poet Laureate (2012-14) and recipient of the North Carolina Award in Literature, the state’s highest civilian honor. He is the author of 20 books. His latest volume of poetry, Light at the Seam, from LSU Press, won the 2022 Roanoke Chowan Prize, awarded annually by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association for best book of poetry in a given year, as well as the 2023 Brockman-Campbell Award, given annually by the North Carolina Poetry Society, for the best book of poetry published by a North Carolina poet in the previous year. The Act of Contrition & Other Stories, winner of the Eastover Prize for Fiction, from Eastover Press, was published in July of 2023. His novella, The Stranger, is forthcoming in 2024 from Regal House Press. Bathanti is McFarlane Family Distinguished Professor of Interdisciplinary Education at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. He served as the 2016 Charles George VA Medical Center Writer-in-Residence in Asheville, NC, and is the co-founder of the Medical Center’s Creative Writing Program. Bahtanti’s flash fiction piece, “Jesus,” won the Summer 2022 Screw Turn Flash Fiction Competition. Author photo: David Silver.

Joseph Bathanti is the former North Carolina Poet Laureate (2012-14) and recipient of the North Carolina Award in Literature, the state’s highest civilian honor. He is the author of 20 books. His latest volume of poetry, Light at the Seam, from LSU Press, won the 2022 Roanoke Chowan Prize, awarded annually by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association for best book of poetry in a given year, as well as the 2023 Brockman-Campbell Award, given annually by the North Carolina Poetry Society, for the best book of poetry published by a North Carolina poet in the previous year. The Act of Contrition & Other Stories, winner of the Eastover Prize for Fiction, from Eastover Press, was published in July of 2023. His novella, The Stranger, is forthcoming in 2024 from Regal House Press. Bathanti is McFarlane Family Distinguished Professor of Interdisciplinary Education at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. He served as the 2016 Charles George VA Medical Center Writer-in-Residence in Asheville, NC, and is the co-founder of the Medical Center’s Creative Writing Program. Bahtanti’s flash fiction piece, “Jesus,” won the Summer 2022 Screw Turn Flash Fiction Competition. Author photo: David Silver.