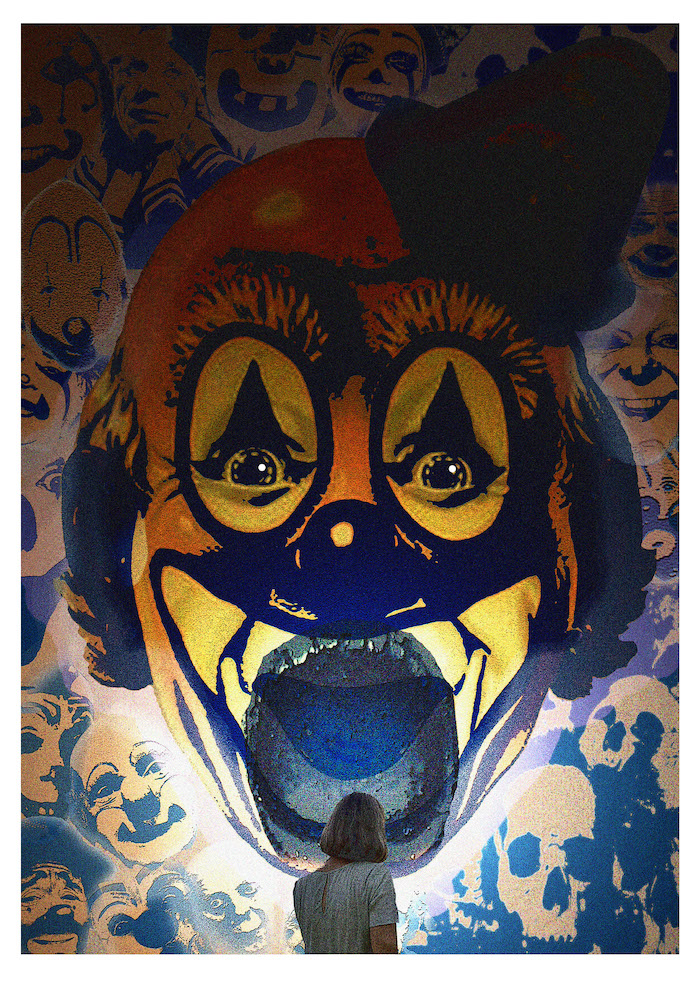

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

WINNER, Spring 2023

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY ANN O’MARA HEYWARD

No one, Maureen reflected ruefully, told you what to expect from aging. Immediately, she corrected her own thought; she was a precise woman with little tolerance for fuzzy thinking. People must have talked about it in her younger, juicier days. But just fully ripened like a strawberry in warm summer sun, you don’t listen.

If you do, you think, never me. I will never be that bitter/dried up/complaining/judgmental. I will age gracefully.

But there’s precious little grace involved. Moving your book to arms’ length to read it, then reading glasses. Just a streak of gray at first, then your brunette days gone, unless you lie with the help of a good colorist. Going for a pelvic exam and finding the speculum now hurts, not just annoys, and being told cheerily, well, things are drying up a bit in there.

Bitterest of all, gradually becoming invisible. As a child, hovering on mysterious edges of adult conversations, she’d thought invisibility would be marvelous. Now, being looked past to the younger, more beautiful, more relevant, was at best a continuing irritation. On bleaker days, it filled her with sadness and made her feel thin and gray, like a ghost.

I’m still here, she wanted to say. Still the woman I was. See me.

She was in line with her sister at the lemonade wagon at the county fair when it happened again. Someone brushed ahead of her in line. A girl in her late teens, barely dressed. The man behind the counter instantly captivated. Hey, she started to protest. Let it go, her sister said, and shrugged.

They bought their lemonades and strolled the midway. Each year they came to the fair together, one ritual that outlasted their childhood, when they had whispered to each other from their twin beds for weeks in anticipation. Each longing whisper naming a pleasure known just once a year. French waffles. Rabbits. Ferris wheel. Cotton candy. Horses. Tilt-a-Whirl. They speculated endlessly about the sideshow tent, which they were never permitted to enter.

Now their fellow fairgoers were the sideshow, Maureen thought. It was fair tradition that each night of fair week was named; the names had evolved with the times. Demolition Derby Night. 4H Night. First Responders’ Night, after 9/11, when police, firemen, and EMTs were admitted free. Once, cruelly, she remarked to her sister that it must be Genetic Disaster night, and for the rest of the evening her sister snorted with guilty laughter every time some new outrageous specimen walked by. It had sparked a game they played at every fair since; they took turns spotting the oddest-looking person they could find and speculating on the object’s back story. By unspoken agreement, the truly genetically afflicted were off-limits; neither of them was intrinsically cruel, but they were pitiless to those who, as her sister put it, did it to themselves.

She spotted hers this year by the funhouse. A man, early thirties, delivering practiced patter to lure passers-by inside, skin shimmering with colors and designs starting just below his jawline. Dark brown hair with blond streaks, pulled into a ponytail. Eyes tipped up slightly at the corners. He looked right at her, across the slow-moving river of people between them. A deep crease bracketed his smile on one side. One gold earring glittered.

Her sister noticed him too. Jesus, he looks like Satan himself, she said, if Satan spent most of his time in the tattoo parlor. Do you suppose he’s up from Hell to buy some souls? He’s staring at you.

I know, Maureen replied, let’s go. Pulling her eyes away felt like a physical effort; a tug that ended in her groin. They turned toward the Arts and Crafts Hall.

The next night, she returned to the fair alone. Whatever Night the fair people were calling it, she knew it was the Last Night. Sleepless since yesterday, she had been unable to stop thinking about the carny in front of the funhouse. Out of all that crowd, he had seen her. One more look, she thought, that’s all.

She made her way to the funhouse and stood across from it for half an hour. She didn’t see him. She looked at the giant clock on the grandstand; the fair would close in an hour.

Fine, she thought, I’ll buy a ticket. She went to the ticket booth and asked for one, please. A bored woman with harshly dyed black hair and an excess of peacock blue eyeshadow on drooping lids took her money and handed her a ticket. Have fun, honey, she smiled, and, unexpectedly, winked.

Maureen walked up the steel entrance ramp and handed her ticket to the bored teenage boy posted there. She stepped carefully and quickly through the entry, a giant spinning barrel. Then, through an undulating curtain of heavy rubber-coated strips that reminded her absurdly of going through a car wash. Beyond, a room with walls, floor and ceiling covered in images of clowns, glowing fluorescent under UV light, mouths open in laugher or screams; she was not sure which. She climbed through a clown’s open mouth painted on the wall and slid down a chute, landing on a soft mat, in utter blackness. Cautiously, she stood; a strobe began flashing. Whispers, shouting, maniacal laughter, screams. She thought she heard her name.

She could not see an exit on to the next room; she began feeling her way along the wall, arms and hands sliding in eerie, jerky stop motion in the strobe light. She circled the room; she could not find the door. She tried again, slapping her hands hard against the walls, hoping to pop open whatever door was there. Instead, all she accomplished was a hollow, steely banging that added to the din. Of course, she thought, it must be a trap door in the floor. She dropped to her hands and knees and crawled across the room, feeling for a hinge or handle, not caring about crawling through the sticky film left by countless shoes, fighting rising panic and anger. This was ridiculous.

She sat in a corner of the room and tried to control her breathing, knees drawn up to her chest, arms locked around them. Stop it, she told herself. Maybe something’s not working. God only knew how fair rides were put together; there had been that horrible thing in Ohio a few years ago where a ride had broken and sent riders flying twenty feet into the air. Before they landed on concrete. And died.

That did it. She was not going to be trapped here in this idiot funhouse.

She began yelling, trying to attract someone’s attention. After 10 minutes, her throat hurt. She felt tears start. Goddammit, not only did no one see her anymore, apparently no one heard her, either. The strobe light was stitching a migraine into her brain through her eyes; she closed them.

She heard a metallic screech. The carny she’d seen last night was standing above her, his expression amused and concerned at the same time.

He took both her hands and pulled her to her feet. I’m sorry, she said. No, I am, he said. You’re not the first, you won’t be the last. I’ll walk with you the rest of the way through. His hand was warm and dry, the skin rough and callused against hers. He leaned on the wall she had beaten and bruised her hands against, and a door opened. Call me Jamie, he said, Jamie Harris. Maureen, she replied.

It’s not all scary, he said. They faced a hallway lined with a dozen glittering mirrors in elaborate frames. Let me show you something. Gently, he put his hands on her shoulders and turned her toward a mirror. She gasped in wonder. There she was, twenty years earlier.

Jesus, she whispered, I was beautiful. I didn’t even know it then.

Not was, Jamie said, dimly reflected behind her. Are. It’s just as real as anything else you see here.

Outside the exit, finally. Thank you, she said, embarrassed again under the harsh white lights of the midway. Jamie put his hand on her arm. I think you could use a drink, he said. She looked at him for a moment, then nodded. Come on, then, he said.

They walked through the fair gate. They turned away from the cars parked in straggling rows on the grass and toward a fenced enclosure filled with RV’s and trailers. Jamie led her through the maze of the camp. Campfires dotted the night, carnies in conversation around them. Strings of colored lights swooped up and down from trailer awnings. Finally, they stopped at a nondescript van.

It’s not much, but it’s mine, Jamie said, and flashed his lopsided grin. I saw Nomadland, she said. I always wondered what that would be like. They climbed into the back of the van, on the mattress fitted there, and Jamie closed the doors behind them. Uneasy, she sat with her knees pulled up to her chest again. For a moment, her mother was in her head, shouting long-buried warnings to teen-Maureen.

He pulled a bourbon bottle and cups from a corner and poured for each of them. The whiskey burned her throat, still raw from her panicked yelling in the funhouse. He leaned over and kissed her, tasting of whiskey himself. The hell with it, Mom, she thought. I’m more than old enough to make my own choices. And it’s been a long time. Too goddamn long. Since a man had touched her. Loved her. Seen her.

She even welcomed the tearing sensation as he entered her. It hurts, she thought, but it means I’m alive, and I can still do this, and someone still wanted to, with me. Above her, Jamie’s eyes locked on hers, as tears trickled down the sides of her face. Just for a second, she thought his eyes had slits for pupils, like a cat’s. A trick of the light.

Afterward, she lay beside him, sounds of revelry in the camp around them. A woman whooped with laughter; a dog barked. Someone set off a string of firecrackers, little staccato explosions.

Jamie whispered in the darkness. If you had a wish, what would it be?

To be seen, she said. Not just tonight, but always.

Jamie traced his finger across her cheek, the bridge of her nose, and the other cheek, writing a message in the tears still wet on her face. Your wish is granted, he said. She drifted into sleep, head resting on his arm under her neck.

Sunlight on Maureen’s face woke her. Rough grass pricked her neck, her back, her legs, naked against the ground. She felt her front cautiously; she was draped in a sheet. The pain in her head when she opened her eyes was terrible, immense. She closed her eyes again, fighting nausea. When she could risk it, she sat up and looked around her. The carnies’ camp was empty, just stray bits of trash and flattened squares of grass left behind by the trailers. Her clothes and bag were in a sad, deflated heap beside her.

A hundred yards away, she saw her car, a white island in the empty grass lot. She wrapped the sheet around her nakedness, bent and gathered her things, slipped into her shoes, and began walking. She’d put the rest of her clothes on once she reached the privacy of her car.

She remembered nothing after falling asleep next to Jamie.

One step at a time, she told herself, looking at her feet. Just get to the car.

Finally, she reached it. She raised her head and saw a reflection in the driver’s side window. A stranger. Some woman in her thirties, with a mark across her face. Unrecognized.

Her hands flew to her face. Her hair fanned out in its chestnut glory of twenty years ago, reaching nearly to her elbows.

The tattoo ran across one cheekbone, over the bridge of her nose, and onto the other cheekbone. Elaborate script, surrounded by flowers in more colors than she could name. At first, she couldn’t decipher the lettering, then remembered. The window was a mirror.

Look at me

Tosha spotted her first, then caught the eye of her partner JoEllen on the other side of the Fair gate. Just like clockwork, she said, and jerked her head toward the woman approaching from the parking lot. The woman had been a fixture at the Fair for at least a decade, recognized by the folk who picked up a little extra income for a week by sweeping the midway, taking the tickets, working the food wagons, and stamping the hands of those who wanted to go out and come back in. Eccentric but harmless, was the general view. She occasionally needed to be gently escorted out of the gate by one of the off-duty cops working security, when she clutched one too many sleeves, asking for the funhouse and had anyone seen a young man named Jamie. Her distinguishing feature was a facial tattoo just under her eyes. Tosha had collected her entry ticket at least once and had the opportunity to inspect the tattoo at close range. Look at me, it said. As if, Tosha thought, you needed a reminder. You could tell she’d been pretty. It was a damn shame. What some people did to themselves.

___________________________________________________________

Ann O’Mara Heyward is a horror fiction and non-fiction writer in Cleveland, Ohio. She is at work on a non-fiction book of essays about horror film, entitled The Thinking Woman’s Guide to Horror Movies. Her fiction will be dramatized on the NoSleep Podcast later in 2023 (date TBA), and will appear in a forthcoming anthology from Hellbound Books. Two of her stories are also semifinalists for the 2023 Tulip Tree Review “Wild Women” issue.

Ann O’Mara Heyward is a horror fiction and non-fiction writer in Cleveland, Ohio. She is at work on a non-fiction book of essays about horror film, entitled The Thinking Woman’s Guide to Horror Movies. Her fiction will be dramatized on the NoSleep Podcast later in 2023 (date TBA), and will appear in a forthcoming anthology from Hellbound Books. Two of her stories are also semifinalists for the 2023 Tulip Tree Review “Wild Women” issue.