HONORABLE MENTION, Fall 2020

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

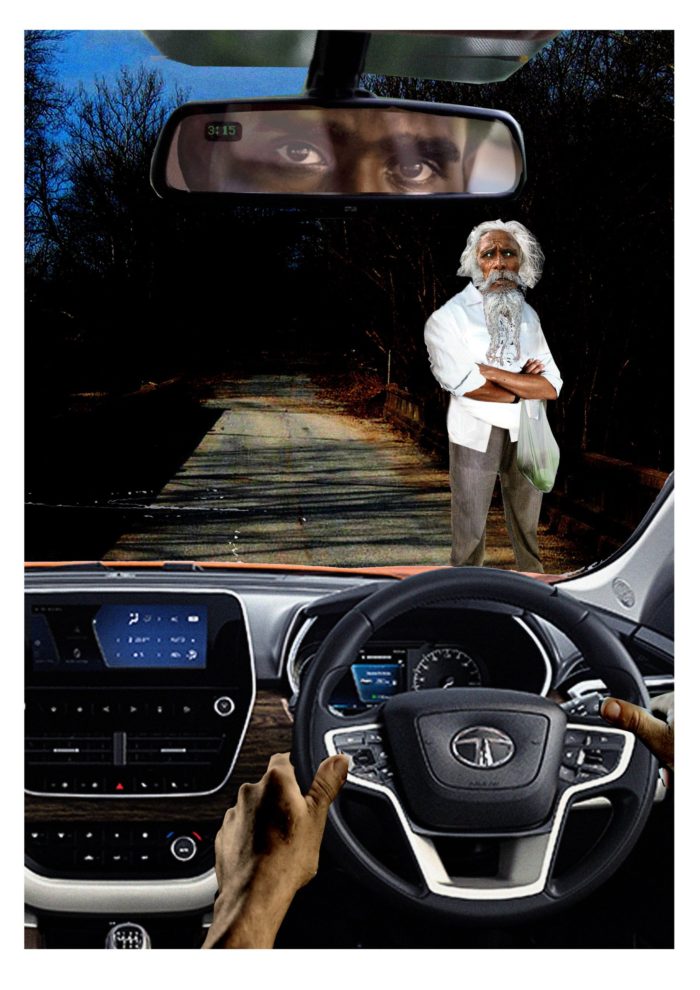

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY KARTHIK KOTRESH

Swaroop Gowder should have listened to his girlfriend’s advice and taken a bus. But he had recently bought a new car and a seven-hour trip to Mangalore on National Highway 48 was too much of an adventure to pass up. Besides, he was meeting her parents for the first time and he wanted to use every opportunity to impress them, starting with his car.

It was quarter to twelve in the night and the city of fish curry and ice cream was still at least four hours away. Swaroop felt an urgent need to piss and decided to take a break. He swerved off the highway and stopped near a small tea shop. It was nothing different from the rest of the shops found on the sides of highways throughout India. You may not always find proper food when you are on a road trip, but you are never too far from a tiny, box-like shop that sells milky tea and cigarettes. Swaroop switched the engine off and stepped out of the car. The silence hit him instantly, followed by the cold, wet chill of the night. He rubbed his hands, zipped up his leather jacket, and walked toward the shop. A middle-aged man in a brown sweater was working his single-flame gas stove.

Swaroop placed an order for a tea and looked around. There were a few houses nearby that looked comfortably asleep, a few street lights here and there, and a paddy field at the far right of the shop. Right behind the shop was a piece of land overgrown with weeds and grass. He hurried to the back of the shop to do his business.

The shop owner gave him a glass of tea when he returned.

Swaroop took the glass. “Ondu King Lights,” he said.

The shop owner gave him the cigarette and pointed toward a plastic lighter that was tied to a gunny thread suspended from a hook in the lift-up door of the shop. Swaroop muttered a thanks and lit his cigarette, facing the highway. He took a sip of his tea, took a puff, and closed his eyes for a second. God, how he missed all this. Going on road trips, surviving on tea and cigarettes and roadside dhaba food. He hadn’t been out of Bangalore in over a year; he had sacrificed a lot so that he could earn, save, and buy an SUV. But no matter. He would utilize his paid leaves more often from now on and travel more. He would take Aparna to Goa in his car soon. It was mid-November now, so maybe for the New Year’s, maybe they could go to—

“Mast caaru. Esht kotte?”

Swaroop swivelled around with a start. Two old men were sitting on the wooden bench in front of the shop with glasses of steaming hot tea in their hands. When did they come, Swaroop wondered as he approached them. Both wore monkey caps and looked a little over sixty. They had green shawls around their shoulders, a symbol of the farmers’ organization in the State of Karnataka. Only this time, they weren’t wearing them to project the strength of farmers as they often did in rallies and functions, but to protect themselves from the cutting cold of the night.

The brazen way one of them had commented on his car and asked its price made Swaroop smile.

“It is good, isn’t it?” he said, glancing at his orange Tata Harrier. Surely, his prospective in-laws would be impressed with him. A 27-year-old marketing executive with a big car could certainly take care of their daughter.

He turned to the men. “Thanks, taatha.”

One of the men, the one wearing a blue monkey cap, repeated the question.

“How much?”

The old man wasn’t going to let it go. “About fifteen lakh rupees,” Swaroop said.

The other old man, the one wearing a white monkey cap, smiled at Swaroop. “My son has a Mahindra. A black one.”

Swaroop sipped his tea, smoked his cigarette, and revelled in the Kannada he was hearing from the old men. Dialect changed every six kilometres in Karnataka and it fascinated him every time he got a chance to observe it. He hadn’t had a chance to meet new people and observe new things lately. He felt as though his feet had rotted from not having travelled outside the Silicon City for so long.

“Where are you going?” blue monkey cap asked.

“Mangalore,” Swaroop said.

“It’s not Mangalore,” the old man said with a crooked smile. “It’s Mangalooru. All you youngsters try to Englishify everything.”

Swaroop spat his tea, laughing. “Correct, taatha,” he said, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. “It’s Mangalooru. And I’m from Bengalooru, not Bangalore.”

The old men, Swaroop’s temporary grandfathers, laughed with him.

Swaroop took the money out of his wallet and handed it to the shop owner. The shop owner stuck out his thumb and made a drinking gesture.

Of course they were drunk, Swaroop thought. He smiled, wished the old men a good night, and turned to leave.

“Wait a second,” white monkey cap said.

The old man eyed the shop owner and the blue monkey cap next to him.

“Leave him alone, Lingu,” the shop owner cried. “I know what you are going to say.”

The old man slapped the air around him, turned to Swaroop. “Look, today’s No Moon Day and you are travelling to Mangalooru in your private vehicle. Alone.”

A jet of cold breeze hit them. Swaroop shivered, but the old man was rock steady, drunk or not.

The old man leaned forward, lowered his voice almost to a whisper. “After you pass a small town, Kalladka, you will come to a bridge with a river flowing under it. It’s an old tar road bridge about a hundred meters in length. When you get there, just drive. There could be someone on the bridge. Do not look at that bolimaga, do not lock your eyes with his, do not stop your car. Eyes on the road and drive. Get away from the bridge as soon as possible.”

The seriousness with which the old man said it made Swaroop uneasy. Was the man on the bridge his friend, his partner of some sort? Was someone waiting to rob him?

The night was getting chillier by the minute. It had become unusually silent as well. No vehicles drove past them on the highway. A moment later a luxurious breeze came whooshing by and broke the silky silence. The old man was still looking at Swaroop intently. Swaroop avoided his gaze and turned to the tea shop owner, caught his eye, and turned away.

“Listen, boy,” the shop owner said. “Don’t mind him. He tells that to everyone he comes across this time of the night. Ignore him and go on now. Safe journey.”

Swaroop nodded, then turned to the old man in front of him and forced a laugh. “So what happens if I look at him?”

The old man smiled. “Safe journey, child,” he said.

Swaroop rubbed his hands, made a fist, blew air into it, and walked back to his car.

He opened the door and just before he got in, he heard the men laughing. He turned around. The three men seemed engrossed in whatever they were discussing. Maybe they were laughing at him. They had played a prank on him. They had played good cop, creepy cop on him, and were now laughing about it.

Stupid grandpas. He shook his head, smiling, and got in the car. The lush leather around him and the warmth of the vehicle were comforting. He turned the key in the ignition, shifted gear with a flourish, and drove.

When he hit the highway again, Swaroop turned up the volume of the car stereo. Linkin Park’s “In the End” came blasting through the speakers. Singing along, he popped the car into the fifth gear and floored the accelerator pedal. He could feel the power of his car. At a hundred kilometres per hour, it was barely idling. Oblivious to the world outside the comfort of his car, he gazed ahead, scoffing at speed limits, and drove on. Music, an open road, the speed of his new car . . . he didn’t want his journey to end.

He decided not to make any more pit stops until he reached Mangalore. Or Mangalooru. He thought about the two old men and laughed. It wasn’t uncommon for people in and around Mangalore to believe in legends like that. The place was famous for ghost stories. Aparna herself had told him plenty of them. One of those involved an old woman acting strangely and telling people things about themselves that not even their closest friends would have known. Apparently, some bhoota had taken over her soul and began revealing people’s secrets to prove to them they weren’t beyond a bhoota’s grip. People were expected to worship it by performing a ritual involving dancing, singing, and sacrificial offerings on a particular day—and if they didn’t, they would suffer greatly. Swaroop had laughed hard at that and Aparna had joined in. But people believed in those things. In southern Karnataka, worshiping both devil and deities went hand in hand.

Whatever else such stories were, they made for interesting talk while having a drink. Preferably around a campfire . . . Speaking of which, Coorg would be a great idea to go to in winters. Book a Homestay in the jungle, build a campfire, drink, and trade stories. Maybe he could call Anurag and Preethi to join Aparna and him for the trip.

It was nearly three o’clock in the morning. He pulled over and checked Google Maps on the dashboard screen. He was somewhere near Kalladka. Mangalore was about an hour and a half away. He drove for another kilometre and slowed down when he spotted some lights in the distance spilling onto the road. A dhaba. The thought of having matar paneer and butter naan was tempting. But when he drove closer, he found the place too filthy even by regular roadside dhaba standards. The last thing he wanted was to go to Aparna’s house with a stomach infection.

His cruise on a never-ending stretch of highway came to an end when Google Maps guided him to take a right from a junction. He cringed and turned into a pothole-filled, narrow road cutting through a forest. He lowered the window, looked out, and let the cold breeze in. The smell of trees was pleasant enough, but the wheels of his car stirred a cloud of dust that itched his nose. He sneezed a few times and raised the window.

The car jounced along the muddy road, crunching weeds and stones, and just when the uneven road cleared and gave way to a much nicer, wider road, Swaroop spotted a bridge up ahead. He slowed down, switched off the stereo, and lowered the window again. He could hear the faint sound of water flowing nearby. The river under the bridge.

Swaroop reached the beginning of the bridge and brought the car to neutral. The car growled against the silent night. The whistle of the breeze mixing with the gentle burble of the river was music to his ears—but the uncompromising blackness of the night was so overpowering it was almost claustrophobic.

Swaroop put his hand on the gear handle and was about to pop it into first when he saw something on the bridge about thirty meters ahead. He reached below the steering wheel and turned the knob that switched the headlight to high beam.

Leaning against the concrete balustrade of the bridge stood the silhouette of a man. Swaroop had heard about miscreants throwing eggs on the windshields of oncoming cars in the night, compelling drivers to turn on the sprinklers and the wipers. That was a classic mistake, because egg yolk and water didn’t mix well and would leave a thick smudge on the windshield, blurring the view completely. Drivers would then have to slow down or stop their vehicles, making it easier for the miscreants to rob them or kill them or both. The method was so simple yet so powerful.

Swaroop switched the engine off and sat in silence. The headlights were still silhouetting the unmoving man on the bridge. Swaroop had no doubt the man was going to try to stop him. But the man didn’t move, didn’t turn his head and look in Swaroop’s direction. He just stood there, staring straight ahead, as if he was having a hard time deciding whether to cross the road and go to the other side of the bridge. Maybe he was—

A sudden rush of cold wind hit Swaroop through the window. He shivered, rubbed the fresh goose bumps on his arms. The wind gusted once again, the leaves in the trees rustled, the river under the bridge gurgled. He checked the time. Three-fifteen. He’d better drive, he thought. He would handle the man if he tried something. Keeping his eyes on the man, Swaroop reached under the steering wheel to turn the ignition key. He held the key between his thumb and forefinger and had almost given it a twist when . . .

. . . the bridge pulled the air around him like a vacuum cleaner sucking dust. The air went whoop before everything outside became still. There was no gurgling of the river flowing, no rustling of the leaves. No sound close at hand or in the far-off distance. Even his breath seemed to die the moment it left his mouth. He felt like prey under the eye of a predator. He felt the air getting hot. Strangely, the car’s dashboard showed the temperature as thirteen degrees Celsius.

He turned the key. The car growled back to life. He revved up the engine, dimmed and dipped the headlight. The man didn’t respond. He just stood there without moving. Swaroop put the car in gear and drove.

On the bridge it became incredibly cold. So cold he started shivering uncontrollably, and feeling as though he were having an epileptic fit. He raised the window.

The man was close by. Swaroop honked once, twice. The man didn’t turn, didn’t move. He was like a figure in an eerie painting, frozen in the colour of shadows, frozen in someone’s imagination. He was staring ahead at the vast expanse of black paint that was the river. Swaroop drove closer, and in the headlights could now see him clearly. He was in khaki pants, his white shirt untucked, and sleeves folded till his elbows. He held a plastic bag in his left hand and his right hand held his left arm at the elbow crease. A round belly ballooned his shirt and his pants stopped short at the ankles. He had a good amount of hair on his head and an overgrown, shabby beard.

Swaroop had one last thought to drive away, but the curiosity that had been building up inside him had already burst and there was no changing his mind. The old man at the dhaba had warned him not to look the man in the eye. But the more you tell your mind not to do something the more it wants to do it. Besides, the man looked depressed and perhaps suicidal, looked as if he were ready to jump into the river. Maybe he needed help.

He drove closer. The man continued to stare ahead, unperturbed by the bright lights of the approaching car.

Swaroop stopped beside him, lowered the window again, and turned to face him. The freezing cold was merciless. A million icy prickles instantly formed on his arms and neck.

The man’s expression didn’t change; he didn’t blink. He didn’t look at Swaroop. He didn’t change the awkward pose of his arms. Swaroop was so close to him he could have reached out and touched him. He looked no older than thirty, could even be Swaroop’s age. Swaroop put his hand out the window and snapped his fingers.

The man’s eyes were blank, dead, no sense of awareness of any sort.

“Hello?” Swaroop said. “Are you all right?”

At the sound of Swaroop’s words, the man finally, slowly, swivelled his head to face him. After a moment his pupils turned a glowing, pulsating green which intensified momentarily before emitting a sudden searing flash and going dull again. Swaroop felt as if someone had lit a match and flicked it into his face. He drew his hand back, rubbed his eyes. What was that? He mopped tears with the back of his hand.

When he looked up again, the man was staring at him. The hell with this, he thought. Swaroop shook his head, raised the window, rolled past the man, and began to drive. Once he was off the bridge, he checked his watch. Three-fifteen. He remembered checking the time when he had stopped at the beginning of the bridge. It had been three-fifteen then. Although at least ten minutes had passed, the digital clock on the dashboard and his digital wristwatch both showed it was three-fifteen now. Or could it be that he was misremembering?

In any case, just half an hour more and he would reach Mangalore. The thought filled him with both anxiousness and excitement. Don’t worry, Swaroo. I know you can charm my parents. It would go well. He had even learnt some Konkani words to impress them. He was going to behave like a perfect—

He slammed on the brakes. The tires skidded, spitting dust and stones, and the car came dangerously close to hitting the balustrade on the left before coming to a stop.

He was back on the bridge. The man was still there, in the same spot, but now leaning against the balustrade. Swaroop checked the time. Both his watch and the dashboard clock said three-fifteen.

He felt the colour of the never-ending night pouring into him and floating to his head and shrouding everything. He stared ahead at the man on the bridge. The mad son of a bitch was looking toward his car.

Swaroop’s hands were now shaking against the steering wheel. He took them off the wheel, balled them into fists, squeezed his eyes shut, and tried to breathe. Maybe he was just tired and his mind was playing games.

He reversed the car and straightened, and as he did so, he caught a glimpse of a faint sheen of silver dancing on the surface of the water below the bridge. Until now he hadn’t been able to see the river, only hear it. But now the stars seemed to have burnt off the clouds and were shining their light on the senseless world below.

Just when he was about to drive on, a fish leapt from the water, soared above the balustrade, hung in the headlights of the car for a second, and popped back down to the water. The bridge was well over fifteen feet above the surface of the river and a fish no bigger than the palm of his hand had just jumped above the balustrade.

He didn’t want to think, didn’t want to apply logic. He took his foot off the clutch.

Swaroop didn’t slow down as he approached the man—who was now studying Swaroop as if he recognized him. Swaroop sped up and was off the bridge in seconds.

He couldn’t help checking the clock again. Three-fifteen. He banged on the steering wheel. What the hell was going on?

He checked the odometer. That shouldn’t lie, couldn’t lie. He kept watching it as the number on the far right rolled up. Good. He drove for a kilometre and the odometer kept changing, drove for another kilometre, and the odometer didn’t seem to cheat. But when he checked the time again, it was still three-fifteen. To hell with it. He was doing seventy kilometres per hour. He would drive his way right out of this.

But he didn’t. He couldn’t.

He was soon back on the bridge.

He had driven straight and hadn’t taken any turns. There weren’t any turns to take. Yet here he was, again. The man looked as if he were waiting for him. He was no longer leaning against the balustrade. He had come off it and was standing straight and looking alert.

Swaroop had no choice except to drive, so he drove. He kept to his left and didn’t slow down. But as he passed the man, he got the feeling there was something familiar about him.

He thought about Aparna—how much he wanted to hug her, to tell her how much he loved her. Even though Mangalore was only a half-hour’s distance, she now seemed so far away.

Within ten seconds of leaving the bridge again he was doing eighty kilometres per hour, then ninety. The car hit potholes and bumps in the road and took the punishment that no new car should. Swaroop didn’t care. He didn’t slow down, didn’t stop, kept his eyes on the road.

And he came back to the bridge.

The man was facing his approaching car. Swaroop zoomed past him, realizing more firmly that he had seen him somewhere before.

He looked to his left and down at the river. All black again. He looked up at the sky through the windshield. The stars had disappeared. He looked ahead and once more he was at the beginning of the bridge. The time gap between leaving the bridge and coming back had been much shorter this time.

He decided to go past the man without looking at him. He drove as fast as he could—and was once again on the bridge within seconds. Shortly thereafter, he found he couldn’t leave the bridge at all, even for a moment. He was driving on it in a continuous loop like a stuntman in a carnival, passing that strange, staring man every few seconds. Each time he looked at his watch or the dashboard clock, it was three-fifteen.

He finally decided he had only one option left: get out of the car, grab the man by his neck and ask him to explain what was happening and who he was.

But when he pulled up beside the man, all his anger went out the window and dissolved into the soulless night. The beard on the man was gone, revealing a familiar black mole on the left cheek. He’d had thick, curly hair before. But now his straight black hair was slicked back with a few wisps hanging over his left eye. His eyes were now dark brown instead of hazel, his nose was not aquiline but straight, his jawline square, and his lips thin.

The man didn’t look like Swaroop. He was Swaroop.

Swaroop took his foot off the accelerator pedal. The car sputtered twice and turned off. Swaroop saw himself on that bridge. A morphed picture of Swaroop manifested into a reality. Swaroop with a potbelly. Swaroop with a skinny face and an undisciplined body. Swaroop with a bad dressing sense.

He didn’t want anything more to do with this man. He didn’t want to ask him anything. To hell with answers. He just wanted to drive, even if he had to keep driving on the bridge until the fuel tank dried out. The night had to give way to the morning and someone would definitely come this way, someone had to.

He was about to start the engine again when something drew his attention to the rearview mirror. The road behind him was empty and silent and dark. He looked again, tilted the mirror a little, and stared into it—and then he jumped in his seat.

His eyes were hazel, his eyebrows were of a different shape.

He opened the car door and stumbled out. He was at an arm’s distance from the man. Breathing hard, he looked at himself in front of him. Then, praying silently, he shuffled to the car door, angled the side mirror, and put his face in front of it.

It wasn’t a night to get your prayers answered. This was not a face Swaroop knew. Not his face; not him. It was the face of the man on the bridge as he remembered him from a half hour or god knows how long ago. That hideous beard. He brought a shaking hand to his face, and the touch of that coarse hair sent shudders through his body. He cried out and leapt backward, tripping over his own feet and falling hard on the ground.

The man who had swapped faces with Swaroop glared down at him. Swaroop scooted backward. Then the man’s eyes seemed to soften a bit. Swaroop thought he saw disappointment in those eyes—eyes that were his until a while ago. The man drew a deep breath and turned away. He walked to the car, got in, closed the door.

Swaroop sat up and watched himself at the wheel. Without glancing at Swaroop, the face-swapper turned the key in the ignition, put the car in gear, and drove.

Swaroop stood, walked back a few steps, and leaned against the balustrade. Around him he saw blackness and nothing but blackness. A moment later the faint sound of an approaching vehicle pricked the absolute stillness of the night. Some hope after all. He crossed his arms against the cold and glanced down at his watch. Three-fifteen. Then he tried to turn his head. He couldn’t. After a moment he realized that he could not even move his eyes, or blink, or open his mouth to scream.

Earlier he had ignored the old farmer’s warning, had locked eyes with the man on the bridge, and had lost his face. Now he was in the frozen grip of the bridge, and all he could do was to feel his heart beating, feel the freezing cold of the night on his skin, and listen to the sound of the approaching vehicle. Perhaps, he thought, the driver would stop and help him.

The vehicle was close by, almost at the start of the bridge.

The time on Swaroop Gowder’s digital wristwatch changed. Three-sixteen.

___________________________________________________________

Karthik Kotresh’s publications include “Hunch,” a short story published by Grey Oak Westland Publishers (India) in 2012 as a part of an anthology, Urban Shots: Crossroads. When not writing fiction, he works as a Copywriter for an e-commerce firm in Bangalore, India.

Karthik Kotresh’s publications include “Hunch,” a short story published by Grey Oak Westland Publishers (India) in 2012 as a part of an anthology, Urban Shots: Crossroads. When not writing fiction, he works as a Copywriter for an e-commerce firm in Bangalore, India.