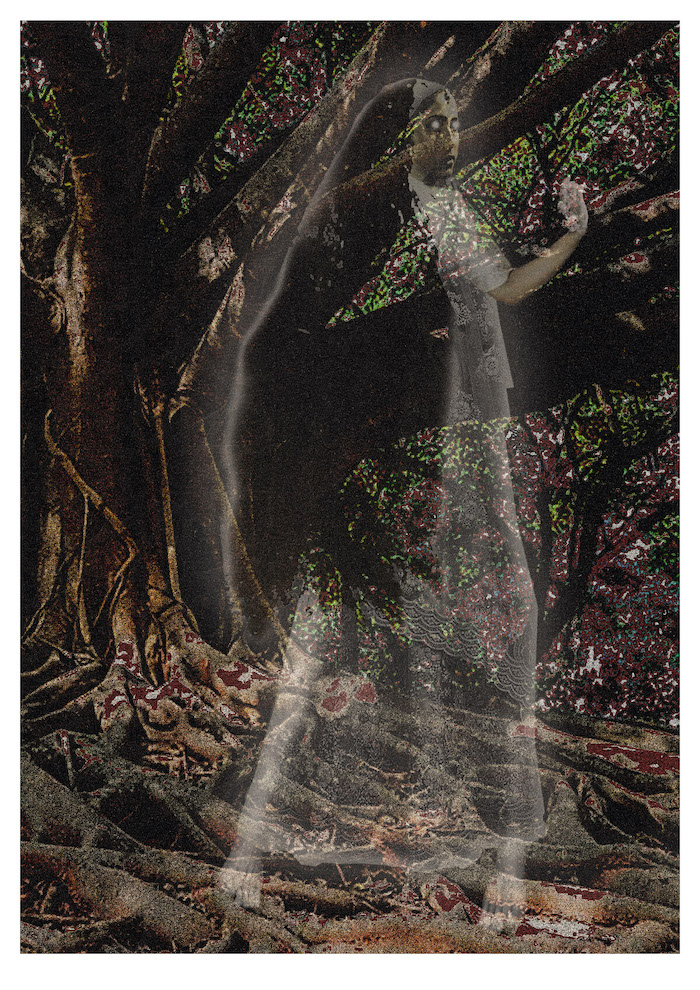

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, Fall 2022

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY IQBAL HUSSAIN

Our mother shadowed our childhoods with tales of bhoot, djinns, paris, nagas, rakshasas and other assorted ghosts and ghouls. Born in a village in the mountains, surrounded by forests, lakes, and whispered words, her beliefs ran deep. She performed every action with an appeasement to one supernatural entity or another.

In her dying days, she read the Quran from sunrise to sundown, entreating Allah to save her from the faceless presence in her room she believed had come for her. She slept facing Mecca, ready to be called to Jannath should her maker summon her in the night.

“Arifa, where are you?” she whispered. I came forwards and leant down, taking her hands in my own. She smelt of snuff, sweat, and something else: the carrion whiff of death. I held my breath. She coughed several times, her weakened body shaking. Blotting her mouth with the end of my dupatta, I tried not to see the red specks blooming on the border.

“Beware . . .” she began, before being beset by another bout of coughing. She lay contorted in pain on the low-slung bed, a broken bird on the rope frame. “Beware of women . . . whose feet . . . point . . . backwards.”

I tried not to flinch. I pressed her hand, entreating her to say something more meaningful. But the effort of talking had exhausted her. She breathed heavily, her eyes rolling in her head.

Suddenly, she looked over my shoulder and gasped. She clutched her taweez—the amulet around her neck. “Ya Allah, show me mercy!”

Those were the very last words she uttered.

She sank back, her eyes wide open, hands twisted into claws and a trail of blood exiting her mouth along with her soul.

My bones crack as I stretch and get up.

Outside, it is humid and the crickets chirp loud enough to wake the dead. I step into the night. The air is still and shimmers with the electric blue of the jacaranda trees that line the paths, the spectral hue of their flowers visible even in the dark.

I have become used to being awake in the early hours. Sleep eludes me; solitude befits me. Beholden to no-one and nothing, I am mistress of my own fate.

I often thought of her final warning. Superstition was so much a part of her that, strange as the words were, they provided comfort in later years—especially after the darkness descended.

She’d meant the banshee-like churails who haunted abandoned houses, peepal trees, and cemeteries on their backwards-facing feet. The spirits of women who had come to untimely deaths. In rural backwaters, you could be killed for any number of reasons: from being pregnant out of wedlock to taking too long to return from the well. Murdered by their loved ones, these wronged women came back as fearsome churails, seeking revenge.

Growing up, Farzana and I had scoffed at the wild tales.

“Look at me, I’m bewitched!” I’d say to my younger sister, baring my teeth and tilting my head while stalking her through the rooms of our childhood home.

“You’re not doing it right,” she’d retort, rearranging her features into an even more grotesque mask and raking her fingers through her hair. “And you need to walk backwards.”

“Thauba, thauba!” chastised Mother, walking into the room with a twig broom in her hand. “What disgraceful girls I have raised. Forgive them, Allah. They are young and silly, with not an ounce of common sense between them.”

I would remind her I was old enough to be taking my matriculation this year.

Mother continued with her warnings, all the while sweeping dust from one end of the room to the other, her nose and mouth covered with her chadhor. “Your grandfather knew someone who gave a girl a lift in the middle of the night. He found her standing outside an old mansion. In full bridal wear. What do you make of that?”

Farzana and I snorted and exchanged sly glances, but Mother wasn’t to be put off. “As a Muslim brother, he could not leave a sister by herself. So, of course, the good man stopped. Who knew what villains were prowling the streets?”

She froze, lost in thought. Farzana cleared her throat.

Mother came back to life, brushing away a cobweb in the corner of the ceiling. “The moon was out. He should have noticed she cast no shadow.” She shuddered at the thought.

“I’m sure he was too busy noticing other things,” I whispered in Farzana’s ear. She squealed. Mother, her hearing as sharp as a bat’s, slapped me, then, for good measure, Farzana.

“Ya Allah, forgive me for raising such vulgar girls.” She touched her ears, seeking heavenly absolution.

“Why could you not bless me with boys?” She waved her broom in our direction. “The poor man was never able to speak after that. His hair turned as white as flour. He spent the rest of his life playing with the goats.”

This set us off again. Mother shooed us out of the house, threatening to tell our father when he returned from the fields.

My beloved Farzana will be an old woman now.

I hope her marriage served her well. I remember the day Father brought her husband-to-be to the house. A man even older than himself. But he boasted land, several score of oxen, and good standing in the community—that was all that mattered.

I would give my last breath to wrap my arms around my beloved sister once more. We were parted, against our wishes. There was no going back—he made sure of that. We are lost to each other, even without the chasm that separates us.

Grandfather’s friend missed the biggest clue. While churails could hide their pig-like features, wild hair, and black tongues in the form of beautiful women, they could not disguise their feet, which pointed forever backwards. Farzana and I would shiver at this deliciously chilling detail.

There were tales of travellers fleeing from these unearthly creatures upon spotting their footprints in the dust. They would run in the direction opposite to the prints, thinking they were putting distance between themselves and the churail. In reality, they were heading straight into her arms.

I had so many questions. How could their feet be back to front? How could they walk? Why were they so cursed? Did the people they attack deserve their fate?

That understanding would only come with age.

I am the only soul abroad. Bats wheel drunkenly overhead, silhouetted against the full moon.

I catch my reflection in the lake as I pass—the “woman in white,” the groundsmen call me. I have worn a pale salwar kameez for so long I struggle to remember the days when Farzana and I would go to the bazaar dressed in our colourful finery.

A fish jumps, sending ripples across the smooth surface. My face dissolves before slowly reforming in the mirror-like water.

The years have been kind. Those chancing upon me remark on my youthful visage, before they . . . well, just know that I am no longer the girl I once was.

My father became even more distant after our mother’s death. He spent his days working the fields. He furrowed his grief into the soil. He would return home covered from head to toe in red earth, his eyes barely visible, hair matted, body bent over, resembling the very devil himself.

He ate alone, with just the whoosh of the ceiling fan and the scuttling geckos keeping him company. Too tired to talk, he became a man of grunts and gestures.

Farzana and I kept our distance, careful not to ignite his temper. We tiptoed around the rooms and courtyard, shunning words ourselves, communicating with each other in nods and glances.

With our silent, half-lived existences, the house sheltered more than one ghost.

Keeping to the shadows, I negotiate the avenues and streets that are as familiar to me as the alleys of my old village. There have been many new residents since I first came here. I struggle to remember them all.

I slip through the heavy gate. Nearby, an owl hoots, its call carrying through the air like the cry of a dying man. A lonely rickshaw sputters past, a filmi song escaping from its glassless windows. The scent of jasmine fills my lungs. I fancy I hear my heart beating.

Mother said churails spirited away naughty children. “Once you hear their steps on the floor, well . . .” She left the sentence trailing, the unsaid words making us cease our clamour.

The churail’s screams filled my dreams. Her screeching outside the window heralded her arrival, clawed feet scraping on the marble floors. Many a night I hid under my blanket, trembling, the ropes of the bed creaking with my every panted breath. I grasped the taweez around my neck, sending up kalmahs to Allah to pray for forgiveness.

I fancied I could smell the churail’s sulphurous stench as she loomed over me. Any moment, the blanket would be thrown back and I would find myself staring into those mad, red eyes.

I know now that churails have better things to do than terrorise the innocent.

I approach the house. It glows white in the moonlight, its many towers rising up like bleached bones. Over the years, the lights behind the shutters have gone out, one by one. Tonight, there is darkness.

I expect to feel a rush of emotion upon seeing the house again. But there is nothing. It seems another lifetime since Farzana and I played hide-and-seek in its many rooms.

A white owl sails past, its body trailing a ghostly path through the inky sky.

As the years passed, Father felt increasing pressure to get us married. Neighbours would tell him how we had grown and that they prayed the evil eye would not fall upon us as single women.

The young men in the neighbourhood were also not afraid of making their feelings known. I lost count of the times I stopped the more daring ones from Eve-teasing Farzana.

We were fair game for every thug, gossipmonger, and do-gooder.

“That’s what comes when you dress like exotic birds,” Father would say to us when we complained of another harassment or ill word.

On my nineteenth birthday he told me: “We could still get a decent dowry for you, but we need to marry you off soon. Else the good families will pass on you, thinking you are too old.”

We knew better than to protest. We were no longer children, when we could answer him back and he would laugh at our wilfulness. Our bodies bore the scars of recent arguments. His belt and raised voice featured in our new nightmares as much as any churail.

The front door is unlocked. With so few houses, and even fewer people, there is little reason to fear for one’s safety. The population of the village has dwindled over the years. The young move on and the elderly stay behind, lost in the shadows.

I pass through the once-familiar rooms, the ghungroo around my ankles chinkling gently with each step. Lizards scurry into cracks, like little djinns at the edge of my vision.

“He’s looking at you,” teased Farzana, nudging me in the ribs.

She meant the boy who helped his father run the spice stall in the bazaar. With his straight nose, arched eyebrows and strong cheekbones, he was as handsome as a movie star. He looked out from behind towers of cumin, cayenne, turmeric, and paprika, his skin pale against the vivid reds and yellows. My heart beat like a dhol drum as his green eyes caught mine. All thoughts of what I was meant to be buying left my head.

With Farzana’s help, I stuttered out my order. I watched him scoop various powders and herbs into paper bags, moving rusty weights around until the pan scale balanced.

My fingers trembled as I counted out the paisas and rupees into his hand. He asked if I wanted anything else. I shook my head, blushing.

As he handed me the bags, our fingers touched. It was all I could do not to drop the spices.

He leant forwards and I caught the fresh scent of mint on his breath. “Come again soon, fair one,” he whispered, every word exotic to my ears. “Maybe we could go to the baagh?” I could think of nothing nicer than spending the day in the park with him. He lay his hand on mine, letting it rest there for a few seconds, before his father appeared.

As Farzana and I walked away, I turned around. Hiis gaze followed me through the powdered stacks, his eyes like a pair of new-season cardamoms. A waft of cinnamon stole out into the breeze. Then he vanished as a cart and ox creaked past.

Nothing moves in the garden. Then, I see him, on the bench by the fountain. He is motionless, frail as a skeleton. Tears prick my eyes. Age has caught up with him. He is no longer the giant of my nightmares. He is an old man, the curve of his back matching the handle of the staff he clings on to.

He sits patiently, oblivious to the gnats flying around his head. He gazes into the distance. A life long lived. Alone. Waiting for the end.

Over the weeks and months, I found more and more reasons to visit the spice stall and the boy with the green eyes. Had Father known, he would have locked me up—or worse. A girl’s izzat mattered above all else, no matter what it took to preserve it.

Vijay’s name alone would send his temper spiralling and his belt flailing. Given the purdah behind which we lived, where even Muslim boys were barred, he was unlikely to welcome one who reminded him of the very sins of Partition.

Farzana and I spent our time looking over our shoulders. Someone might put a word in his ear, saying they’d seen us at the river speaking to this boy or laughing with that one.

“Respectable girls do not mix with unmarried boys!” he thundered, after one such report reached him. “Without her reputation, she is no more than spoiled goods.”

My sister and I spent the night nursing our welts and falling into troubled sleeps.

It is hard to imagine the strong man he once was, ploughing the fields with his oxen for days on end. Now, as his hands tremble against the head of the wooden crook upon which he leans, he would struggle to lift a pen.

I begin to doubt my own memory. I should not be here. This is wrong.

Then he laughs to himself—a mirthless sound—and it comes rushing back.

“Tell me what you’re thinking,” said Vijay, trailing a marigold over my face. My head in his lap, I gazed up, noticing how the dappled sun created a halo around him.

I traced a finger over his hand. “How I never want this to end.”

Even as I said it, I knew how impossible it was. If Father saw me now, he would drag me home. Worried about what the neighbours would say and the shame I had brought upon the family.

Vijay stroked my cheek. “I wait for you each day, hoping you will come and stop by,” he said, his mouth inches from mine. “And, when you do, my mind goes blank and I forget everything. My father tells me off as I get the spices mixed up and drop the money and mislay the weights.”

He lowered himself down on his elbow. “I am away in my own world, soaring among the stars.” His finger traced the outline of my lips. My body quivered at his touch. “I praise the Almighty for bringing you into my life. When you look at me, nothing else matters. You are the Heer to my Ranjha,” he finished, comparing us to the legendary lovers.

I could burst with happiness. He talked just like the actors in the films. He was as dashing as Dilip Kumar or Rajesh Khanna. Even better—he was real. He was sitting with me, rather than with any other girl in the park. I closed my eyes and gave a contented sigh.

I felt his breath on my eyelids. With a touch as delicate as a butterfly landing on a flower, his lips rested on mine. The world stopped. I heard the rustle of the insects in the grass. He smelt of warming spices: cardamoms, nutmeg, cloves, and mace. The curl on his forehead caressed my skin.

A shadow fell across my closed eyelids: Farzana, telling me it was time to go.

My step falters. It has been so long since I have seen him, yet he has the power to unnerve me still. I chide myself for feeling this way.

He looks up, then gasps. The blood drains from his face. “You!”

I walk toward him, concentrating on each step. “Father. I have come.” My voice trembles and I find myself stopping. I am a little girl again. How can he terrify me after all this time and after everything he has done? With some effort, I force myself to continue.

He struggles to rise, wobbling on his walking stick. “No! Ya Allah, this cannot be!”

A grim smile crosses my face. I keep moving in his direction. The grass is overgrown and tickles my sandalled feet. “Do you not recognise me, Father?”

He stumbles backwards, not letting his gaze fall from mine. “No! You are a figment of my imagination. Be gone, Shaitan! Go—I command you!”

I put out my hand. “Touch me, Father.”

By now, he is spluttering, his eyes wide in horror. “You have not aged a year. How can this be? Why . . . how can you be here? Your face still so . . .” He touches his own face, which is riven deep with wrinkles. “Who are you? What are you?”

I don’t know who told Father. But he found out soon enough.

“Who is he?” he said, slamming open the door of the kitchen.

The knife slipped on the onion I was chopping, narrowly missing my fingers.

He came up behind me, his breath on the nape of my neck. An image flashed into my mind of a bullock about to charge. I gripped the knife.

With my heart thudding against my chest, I slowly turned to face him, the knife hidden behind my back. My cheeks were flushed, and not just from the flames of the stove.

“Who is he?” he repeated, louder.

“Who, Father? Why are you home at this hour?” I said, keeping the fear from my voice.

“Bring him round for dinner,” he said.

I opened my mouth in surprise. By the time I managed to get my thoughts in order, he had left the room, not waiting for my answer.

He shuffles away from me, his steps tottery, his grasp on his stick as tenuous as his grasp on his new reality.

I pull back the sleeve of my kameez. “Look! Did you not inflict these on me yourself? Come closer, Father. Take a look. Accept your handiwork.”

I am almost upon him. A breeze picks up and fans my hair around my face. I rub my swollen belly with hands like claws, the nails long and sharp. My mouth opens in a grimace and an unhuman yowl escapes from my very being.

There is nowhere left for him to run. He is pinned against the garden wall. He will face the truth. I will make him pay his due after all these years.

He begs for forgiveness. He cries like a baby, the last vestiges of his already fragmented mind collapsing like a wooden bridge in the monsoon floods. His legs buckle and he slides down, staring up, terror written large across his face.

As I bend down, I see myself reflected in his trembling eyes. I do not recognise myself.

Too late, I realised Father never had any intention of welcoming Vijay to the family. It was simply a ruse to get him round. No daughter of his was going to marry an Indian boy.

Before I knew what was happening, there was a splash of liquid, the strike of a match, and the whoosh of kerosene. Vijay tried to stop him, but Father pushed him back. He slammed the door shut and turned the key in the lock. We were trapped inside.

I heard Farzana banging on the door, screaming at Father to let us out. Her cries were soon drowned out by the ferocious crackling of the fire.

Vijay and I cowered in the corner, behind the armoire, clasped in each other’s arms. This wasn’t how it was meant to end, I sobbed into his neck.

The last thing my father sees are my feet, visible under the hem of the lehenga. His screams shatter the night air. But he lives alone and the house is secluded. As his dying pleas fall away unheeded, their sound is replaced by my greedy slurping.

I take my fill. I do not finish until his body is a husk.

The hunger that has gnawed at me for years is finally sated.

The last thing I remembered was my beloved’s kiss on my cheek as his hands stroked my hair. He told me how happy I had made him and how our love would never die.

Then the choking smoke gathered us in its embrace. The flames licked all round and the heat ripped through our lungs. We shook and coughed and cried, and shook no more.

I get up as the cockerels welcome in the new day. Light-headed, it takes me a few moments before I stop swaying. I rest my hand on the trunk of the peepal tree. A breeze rustles its leaves. I let my breathing return to normal, then I wipe my face with my dupatta.

The sky is already turning from indigo to vermillion.

I walk out for the last time—this time of my choosing. I cast not a backward glance at the house nor at the man I am finally able to leave behind. I walk with renewed zeal. My earlier footsteps stand out against the dewy ground, leading me back to where I started. Reflecting on the stories Mother told us all those years ago, I smile: she spoke the truth.

The grounds are still empty. The visitors won’t begin to arrive for another hour. From the lake, a flap of wings as a stork senses my presence and launches into the sky.

The first of the groundsmen cycles in. As he swings the gate shut behind him, the clang of metal makes me pause and turn around. He judders to a halt, throwing up dust clouds. I hurry on into the copse.

He calls after me, but comes no closer. “You! Woman in white! Stop!”

Except the front of my kameez is now stained crimson. A river of red runs from the neck down to the hem, glowing like an ember as the rays of the rising sun travel up my body.

I climb the steps and then descend to my chamber. It is as icy as any grave, but I welcome its cool embrace. I am tired—blissfully, happily, ecstatically tired. I have been awake for such a long time. Every part of me aches. The years have finally caught up with me.

As I repose, I hear a voice in my head.

I cry out: “My darling, I am coming! Your Arifa is coming!”

The earth settles above me. The sun rises. The world turns. I close my eyes.

I have paid my dues. Vengeance was mine.

Before the darkness claims me, I send up a final prayer:

Ya Allah, show me mercy.

Iqbal Hussain lives in London with his partner and his labradoodle. When not writing words, he writes music, and would love to score a musical of Dracula one day. “Look Not Backward” set in rural Pakistan, is based on stories of a ghostly creature called a churail, which his mother used to tell him when he was a child. His ghost story, “The Reluctant Bride,” also set in rural Pakistan, was published in the Mainstream anthology, published by Inkandescent in 2021. Another of his stories will appear in an upcoming anthology by Lancashire Libraries. He won the Gold prize in the Creative Future Writers’ Awards in 2019, and was a recipient of the inaugural London Writers’ Awards in 2018.

Iqbal Hussain lives in London with his partner and his labradoodle. When not writing words, he writes music, and would love to score a musical of Dracula one day. “Look Not Backward” set in rural Pakistan, is based on stories of a ghostly creature called a churail, which his mother used to tell him when he was a child. His ghost story, “The Reluctant Bride,” also set in rural Pakistan, was published in the Mainstream anthology, published by Inkandescent in 2021. Another of his stories will appear in an upcoming anthology by Lancashire Libraries. He won the Gold prize in the Creative Future Writers’ Awards in 2019, and was a recipient of the inaugural London Writers’ Awards in 2018.