Literary Ghosts: The Importance Of Hamlet’s Ghost

European playwrights and poets have incorporated ghosts into their work at least since the time of Homer. But until the time of Shakespeare, most literary ghosts had two things in common: 1) They were generally served up as “light fare” whose main function was to pleasantly frighten or otherwise entertain the audience rather than to deepen the audience’s understanding of the human mind and imagination, and 2) They were meant to be taken literally as ghosts; in other words, the audience was given no reason to think that the ghost was anything more or less than the actual shade of a departed person.

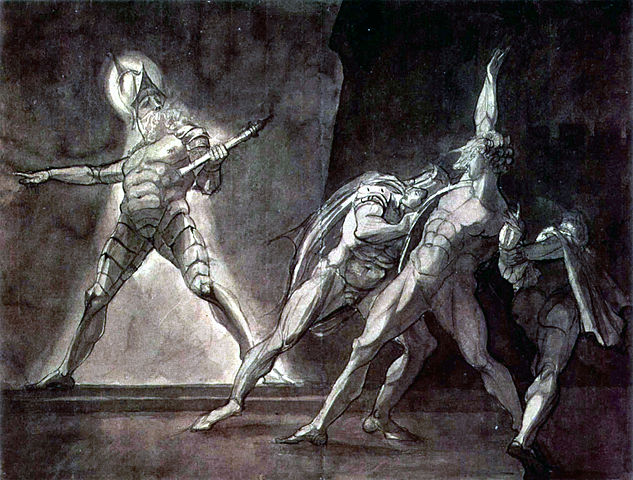

Then came Shakespeare, who along with his other astonishing innovations was one of the first Western writers to offer the possibility of a psychological ghost as opposed to a literal one. In Hamlet, most notably, Shakespeare leaves open the possibility that the armored ghost of Hamlet’s father may at least in part be the product of Hamlet’s own mind—specifically, a manifestation of his guilt at his failure to take action against his father’s murderer.

In fact, Hamlet may be the first ghost story in any language in which a spirit is intentionally deployed to reflect the inner state of the character it has come to haunt.

A later Shakespearean wraith with a psychological provenance appears in Macbeth. The Macbeth ghost is that of Banquo, a contender for the Scottish throne whom the eponymous protagonist, Macbeth, has caused to be murdered. When, during a feast immediately following Banquo’s death, Banquo’s ghost appears to Macbeth—and only to Macbeth—it is readily apparent to the audience that the apparition may merely be a figment of Macbeth’s guilty and anxious imagination.

Ghosts also play a minor role in Shakespeare’s early play, Richard III. On the eve of the evil Richard’s final battle a number of people he has murdered show up to berate and taunt him. And in Act IV of Julius Caesar, written close to the time Shakespeare penned Hamlet, the ghost of Julius Caesar appears to Brutus, one of his murderers, and may—as with the ghosts in Richard III—represent the living character’s dread concerning the possible outcome of an upcoming battle.

In Shakespeare’s wake, psychological ghosts began making occasional appearances in the stories, novels, and plays of other writers. However, most authors continued employing ghosts for thrills and entertainment. It wasn’t until the 1899 publication of Henry James’ short novel, The Turn of the Screw, that the psychological ghost story truly entered its Golden Age.