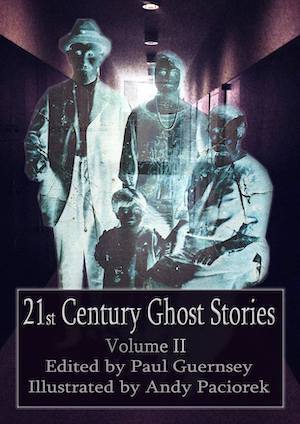

Clytemnestra’s Ghost Is On The Left. This Period Illustration May Look Tame—But Legend Says A Female Audience Member Died Of Fright At The Play’s Premiere.

Before 458 BC, Literary Ghosts Played Minor Parts

Elsewhere on this site, we’ve discussed ghosts who played “walk-on” roles in Homer’s epic Greek poems, the Illiad and The Odyssey. We also mentioned the one significant—though very brief—ghost story in the Old Testament.

It wasn’t until about four centuries after Homer that Aeschylus, the ancient Greek playwright known as “the father of tragedy,” gave us one of the first fictional works in which a ghost took a central dramatic role. The work is called The Eumenides, and it is the final play in a trilogy collectively known as the Oresteia, all of which deal with the murder and its aftermath of King Agamemnon by his wife, Clytemnestra, in the wake of the Trojan War.

The Euemenides is plotted a bit like a contemporary soap opera—an extraordinarily dark and twisted one—so bear with us here:

At the start of The Eumenides, Clytemnestra is dead, having been murdered during the preceding play by her son, Orestes, out of vengeance for her own slaying of his father, Agamemnon—whom she killed to avenge Agamemnon’s sacrifice to the gods of their daughter, Iphigenia. In the Temple of Apollo, the ghost of Clytemnestra appears before the three deeply sleeping Furies—hideous and terrifying goddesses of retribution—in order to loudly demand that they wake up to pursue and punish Orestes (H.W. Smyth translation):

. . . [H]e has escaped and is gone, like a fawn; lightly indeed, from the middle of snares, he has rushed away mocking at you. Hear me, since I plead for my life, awake to consciousness, goddesses of the underworld! For in a dream I, [Clytemnestra], now invoke you. [To which the sleeping Furies respond with a horrifying chorus of whining and moaning.]

. . . Whine, if you will! But the man is gone, fled far away. For he has friends that are not like mine!

FURIES’ CHORUS [122] (whine) [The Chorus continues to whine.]

GHOST OF CLYTEMNESTRA [122] You are too drowsy and do not pity my suffering. Orestes, the murderer of me, his mother, is gone!

CHORUS [124] (moan) [The Chorus begins to moan.]

GHOST OF CLYTEMNESTRA [124] You moan, you drowse—will you not get up at once? Is it your destiny to do anything other than cause harm?

CHORUS [126] (moan) [The Chorus continues to moan.]

GHOST OF CLYTEMNESTRA [127] Sleep and toil, effective conspirators, have destroyed the force of the dreadful dragoness.

CHORUS [129] [With whining redoubled and intensified.] Catch him! Catch him! Catch him! Catch him! Look sharp!

GHOST OF CLYTEMNESTRA [131] In a dream you are hunting your prey, and are barking like a dog that never leaves off its keenness for the work. What are you doing? Get up; do not let fatigue overpower you, and do not ignore my misery because you have been softened by sleep. Sting your heart with merited reproaches; for reproach becomes a spur to the right-minded. Send after him a gust of bloody breath, shrivel him with the vapor, the fire from your guts, follow him, wither him with fresh pursuit!

At this, the Furies then do rouse themselves to chase down and punish Orestes (depicted below by an artist during the 1800s). According to ancient legend, the scene in Apollo’s temple, with all its shouting, whining, and moaning, was so terrifying that a woman at the play’s premiere fell over dead from fright. (One imagines that the very next night, every teenager in the Athens of 458 BC was lined up outside of the theater in order to purchase a ticket.)

In The Eumenides Aeschylus pioneers two traditional uses of ghosts in in all subsequent literature: 1) As a catalyst for action by demanding vengeance on the part of the living, and 2) To produce pleasurable, perhaps cathartic, feelings of fear in the audience.

It is clear that the ancient Greeks enjoyed a good scare as much as anyone.