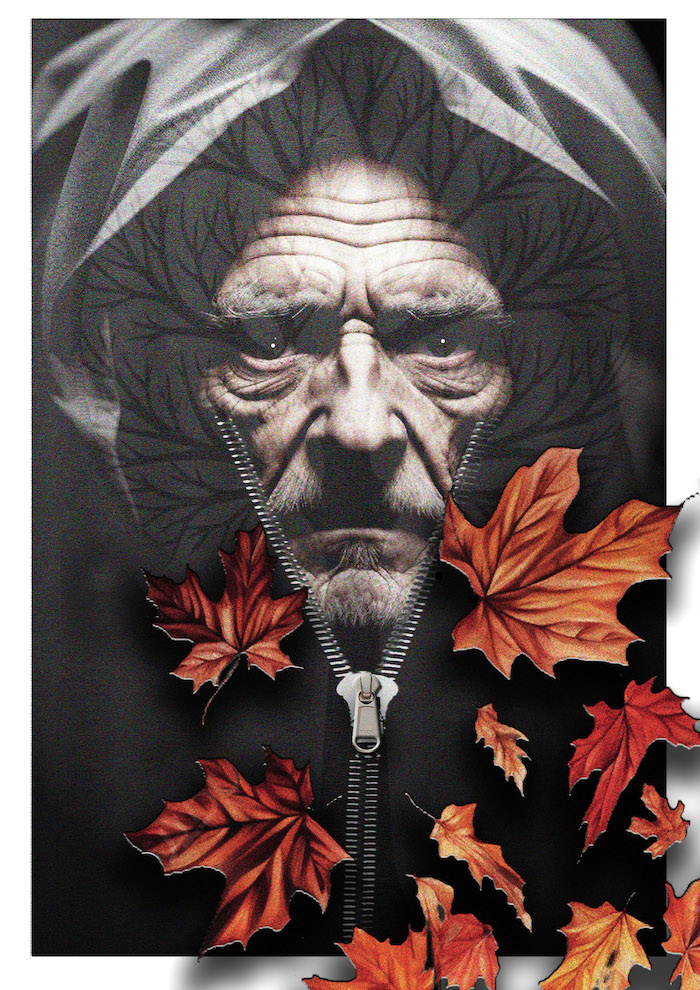

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

WINNER, Spring 2024

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY TIMOTHY ZIEGENHAGEN

The first time I saw the dead man I was going to visit my girlfriend in the hospital. She’d just had a major bleed from an esophageal varice, and I was trying to find her room, making my way through a maze of corridors. It was the kind of hospital where you could get really lost, where hallways turned into loading docks, and the public bathroom was always four left turns, then two water fountains past X-ray. On high alert, I slipped by a hospital room, only half-looking but seeing, you know. The door was only partly open, which limited my view, and I could only see the face of a skinny man on a bed, a long face like the prow of a ship, and then it was zipped up—chin, nose, then hairline—into a body bag. He had probably been about my age, three head colds past forty.

When I got to my girlfriend’s room, she was still down in X-ray, so I sat down on the folding chair opposite the mirror and watched myself think about the dead man. Nurses really ought to keep doors closed at all times in a dead room. Nobody should hear the fly buzz or see stray horny yellow toenails sticking out from underneath a bedsheet. I’d become a part of something, seen something I wasn’t supposed to see, like the faces of the victims in those photographs taken by the Khmer Rouge moments before they executed their prisoners.

The shadows grew long in the hospital room, and finally the transport specialist wheeled my girlfriend into the room. She smiled like I had brought her an armful of flowers, but I had only brought the transdermal nicotine patches she’d texted me to bring. “You’re looking all right,” I told her. “No more smoking,” she said. “I mean it this time.”

Within five or six weeks, my girlfriend found a higher purpose, lost drinking, and then lost me. When we broke up, she told me that she had taken up curling, threw stones in Wausau now. She might as well have told me that she’d taken up pine-cone eating like Euell Gibbons. “Why curling?” I asked her, packing up my overnight bag.

“The broom calms me,” she said, “and the sheet put things into perspective.” She didn’t say it, but I was just another stone being tapped out of the house. I learned a lesson that day: You can’t compete with curling.

So, she started her new life, and I settled back into my old one. Occasionally I would think back to the hospital, remember the nose getting zipped into the body bag and wonder why I’d seen that. I wondered if I’d said yes to something without saying yes.

I was a car salesman, and I moved through my days selling Ford trucks to accountants and trying to stick college kids with used cars that had transmission problems or phantom stall issues. Most nights after work I would drive to Ponderosa, or The Longhorn, or Denny’s and read the newspaper, picking it up and shaking it out like maybe I could throw all of the bad news onto the restaurant’s worn carpeting. I’d go to Sir Orfeo’s and have two or three Old Fashioneds, listening to whatever Rat Pack crap they played to make customers think JFK was going to come back from the dead and buy everyone in the place a fancy drink.

Then I saw the dead man again. It was at Hap Montelle’s funeral, a few months after the incident at the hospital. Hap had worked at the Ford dealership with me, and he sold the cars while I sat behind a closed door approving the deals. He wasn’t married and didn’t have many friends, so the place was crawling with co-workers, vendors, and the odd mechanic. I made extra sure to sign the guest register and scrawled some condolences; it felt like I was adding my name to a drawing at the grocery store.

Two visitations were going on at once that night, and another dead man rested in the adjacent viewing room, with a whole different set of mourners than the ones Hap had. He looked just like the guy I’d seen zippered up in the hospital—oversized caterpillar eyebrows, the prowlike face. These other mourners seemed stunned by their loss. There were pocket-sized obituaries printed on grey paper that said that their dead man’s name was Jim Timber. In life, the obituary said, Jim had loved metal detecting and numismatics, and he was locally famous for finding a 1903 $5 gold liberty coin worth more than $10,000. He had been a loving husband and father. The expression on his face had been adjusted from the hospital—he looked serene, not as hollow or as wan as before, but it was the same man, or his twin brother.

“He’s gone,” said a woman who might have been his wife.

An ancient priest was holding her hand. “I remember him as an altar boy. He was always chewing on Junior Mints.”

“How could he just leave me like that?” the woman asked.

“It was not his choice,” the priest told her, leaving the second part of that sentence wisely unsaid.

I left unsettled, but things went on as before: I sold cars, ate forty-dollar steaks, and drank my cocktails. I checked Match.com and saw that a woman from Carbondale, Illinois had winked at me. I didn’t wink back. Love suddenly seemed like too much work, so I deleted my profile and watched Turner Classic Movies. They had colorized Casablanca, and Rick Blaine had peach-colored skin, like he had been livened up with rouge from an embalming table. I would sit on my couch at night and flip through one website after another on my phone. I always ended up at the Kelley Blue Book website. You can learn a lot about the world based on the price of particular used cars. When a customer came for a new car, I never offered them book value in a trade. I never even admitted there was a book. Every trade ever made went back to the first time somebody exchanged a cowrie shell for a sliver of dried jerky. Crows were the best traders ever. You fed them all winter long and they gave you a shiny bottle cap for it. The lesson in all this: Learn from the crows.

The next time I saw the dead man—Jim Timber, I remembered—I was sitting on a folding chair watching the Wisconsin River flow south. The city park dated from the WPA era and had a stone building with dressing rooms and concessions for the city swimming beach. Timber was wearing swim trunks, and it was strange to see him alive and walking, his pale legs and skinny chest so vulnerable in the July sun. He stretched and flexed and walked down to the beach, then dove into the river. I watched him catch a current that dragged him away from the beach. A voice said that I should go in after him, save him—he seemed to have a propensity for dying, after all—but then Timber looked like a strong swimmer, and maybe he was unsinkable, like his name. Ten minutes later, I was surprised to see him return to shore and rise from the lake, pale and shimmering like the moon. Timber laughed at something a kid on an innertube told him.

He disappeared into the concession stand, and I didn’t see him come out again. Maybe I got caught up in the story I was reading and just missed his exit. The Wisconsin River flowed past. Maybe my dead man had gone back into the river—maybe he was tangled in the weeds, drowned, and I’d missed the whole thing. Eventually, I left, and everything seemed to have gone back to normal, with the dead staying dead, like they were supposed to do.

A few months after that I was at work at the car lot, smoking a cigarette in the picnic area just outside my office window. I had been promoted to senior manager. It was late afternoon, and the light seemed to shift as the clouds blocked out the sun in an instant. A storm was coming, so suddenly that it seemed like I’d called it up by myself.

A quick splash of rain hit the vehicles parked on the lot, and I went inside to sit at my desk and wait for loan offers. During a rainstorm no one buys cars, though, so I went online and played some video poker, then checked the price of Bitcoin. My phone buzzed and it was Amber Ordinary, the best salesperson on the lot. She had a prospect sitting in there with her, so I told her to come back into my office.

Amber was 25 and smart. She liked to pin up her hair like Betty Davis and was a changeling with the customers, be anybody they wanted her to be. She could waste all kinds of air talking to them about fishing lures, mid-century modern furniture, the best lighting tracks for your dining room, or who’d just been ripped apart by jawless zombies in The Walking Dead. She came into my office and I could see she was annoyed. “I’ve got a Hoover Dam in there,” she said. That was her name for a customer who couldn’t be budged from an offer. “He wants an Explorer at $2000 below cost.”

“Can’t do it,” I told her. We talked for a few moments about her vacation in Duluth, Minnesota. We stretched things out, so the customer would know we were in serious negotiations. In Duluth, she’d toured a mansion where an old lady had been murdered, watched ships needle through the aerial lift bridge, and bought some pine-accented coasters from a Scandinavian gift shop in Canal Park.

“That guy in the next room has stewed enough,” she said, finally. “I better go see if I can shoehorn Mr. Tough Bargain into some kind of a showroom deal.”

Five minutes later she called me on the phone. “He wants to talk to you or he walks,” Amber said.

I thought, Let him walk, but I always liked a challenge. If I could get the guy to commit to $100 over cost, that would be a victory. Then we would fleece him on the trade in and maybe upsell him on extended warranties, paint sealants, and a toxic coating of fabric protection for the interior upholstery.

Amber brought the customer into my office. There next to my framed high school diploma stood Jim Timber. He looked a little younger than when I’d seen him at the beach, and he was wearing thick mod glasses. My heart skipped a beat, but I had on my poker face, as always.

“Good to see you again,” Timber said to me.

“Have we met?” I asked, hand gripping a pen.

“You know. At the beach,” he said. “Other times. But about that Explorer . . .”

Amber waved him to a seat but he remained standing. I kept a mirror across the room, because I always liked to watch myself when I made a deal. It was a confidence thing—you didn’t back down and take a bad offer when your own reflection was holding you accountable. But my reflection looked scared, ready to buckle and agree to anything. I was scared. Jim Timber terrified me. I just wanted to escape from that room, that mirror, that face. Anyway, how do you bargain with the dead? “You can have the Explorer at cost minus 2k,” I told Timber. “Get it done, Amber.”

She gave me a strange look on the way out the door: It was the first time she’d ever seen me lose.

That night I got home after nine, as always. I had a bag of Steak and Shake hamburgers, which I tossed on the ottoman. I poured myself two fingers of vodka and added a single ice cube and a spritz of lime juice. I was already loose from Sir Orfeo’s. There was nothing on TV, not even bad colorized movies. Outside the rain was still falling, and I could tell it was going to rain all night. I sat there in the living room, drinking the vodka. My cellphone sat on the coffee table in front of me; the screen was black as a beetle, and electricity in the air told me it was going to ring soon. In the window, I looked like a stranger. The glass distorted my body so that my legs looked broken, refracted into a strange angle.

Jim Timber was after me. I’d seen him zipped into a body bag at the hospital and that was something I wasn’t supposed to see. Had I signed some dotted line just by looking into the wrong doorway? I scrolled my phone to LinkedIn, and there I was, with my laundry list of sales jobs, starting with Radio Shack in 1998. My contacts were the same. There was the thumbnail of my round grinning face with four minutes of stubble. I clicked on the photo to expand the image, make myself bigger, become more of a presence. The enlarged picture scrolled down over the screen of my phone, but it was no longer me anymore: I had lost weight, thrown a tire, grown a prow of a face. Jim Timber stared back at me from my own LinkedIn page. Following a hunch, I typed in my name, and there was Jim Timber’s obituary with my own face beaming back at me.

From the next room, the boards in my kitchen floor groaned. Had someone followed me home? Was Timber sitting at the kitchen table in the dark? I thought again about his face at the hospital, zipped into the body bag. The dead have nothing to do but wait in their black holes, thin filaments of spirit vibrating in time with the emotions or the fears of the living. I wondered if you could get the dead’s attention, somehow, by seeing them at an unexpected moment like I had. Pulling myself off the couch, I was stifled by dread, but there was no one in the kitchen.

A fly buzzed from the TV room. I left the kitchen and went back to the couch, willing myself into the cushions. I turned on the television and flipped channels. Poured myself two more fingers of vodka. I would follow my routines because that’s what a self is: Do this, then do that. You are what you do. The existentialists had taught us that much, at least. On late night TV all the comics were tearing into Madonna because she didn’t look like herself anymore.

Later, sometime after midnight, I went into the bathroom to brush my teeth. When I pulled open the medicine cabinet, I heard the rustle of someone walking down the hallway carpet. I could discern a long thin figure pass into my bedroom in the cabinet mirror door.

I could see the darkened doorway to my bedroom. There was someone lying on the bed. The upper body was shrouded in shadows, but I recognized the socks, the lucky horseshoe pair I’d pulled on early that morning. Had I been glamored? Hynotized? Fear bled out of me.

“I have to be to work early tomorrow,” Jim Timber said, from the shadows. “I’ve got a lot of cars to sell.”

“When you walk into the office tomorrow with that prowlike face, all of my coworkers will know you are an imposter.”

“No. They won’t.”

“My best salesperson, Amber Ordinary—she will know.”

“No. She won’t.”

“You met her! You’re the guy who bought a truck from her yesterday, below cost. She’ll remember you!”

“She won’t know me from Adam.”

My joints were frozen, stripped bolt sockets. I felt like I was being zipped up. My head was swimming, a riptide pulled me down. I shambled across the hall and stood next to the bed, empty now. I slipped like a ghost under the covers and felt myself being drawn away, down deserted hospital hallways, bright with fluorescent lights and empty as a skull. I was somebody else now, maybe. Or just myself, only more so. I was an explorer, no longer afraid at all.

When I woke up, I was in complete darkness, my arms jammed against my chest. I raised my right hand and rapped knuckles against a very low ceiling. I knew what I had to know: I had to wait, not lose my nerve. Somebody else would come along, maybe. As I ran my hand along the surface above me, I felt the build-up of static electricity and recognized the smooth skin of satin over wood. My skin crackled as my fingers brushed the lid of what I knew was a coffin. The static electricity moved along my index finger, a swelling surge of latent fire, then it sparked, and in the flash I saw my fingernails gleam against the image of an embroidered tree in the lining of the coffin—a tress with bare branches, leaves all fallen.

___________________________________________________________

Timothy Ziegenhagen grew up in rural southern Minnesota and attended college at a small university on the prairie. He worked for a time as a bartender in a casino before going on to get a Ph.D. in 19th Century British Literature which, as he explains to his students, is the closest thing you can get to a degree in monsters. He teaches at Northland College, an environmental liberal arts college in Ashland, Wisconsin. He lives within walking distance of Lake Superior and loves observing the great lake’s many moods.

Timothy Ziegenhagen grew up in rural southern Minnesota and attended college at a small university on the prairie. He worked for a time as a bartender in a casino before going on to get a Ph.D. in 19th Century British Literature which, as he explains to his students, is the closest thing you can get to a degree in monsters. He teaches at Northland College, an environmental liberal arts college in Ashland, Wisconsin. He lives within walking distance of Lake Superior and loves observing the great lake’s many moods.