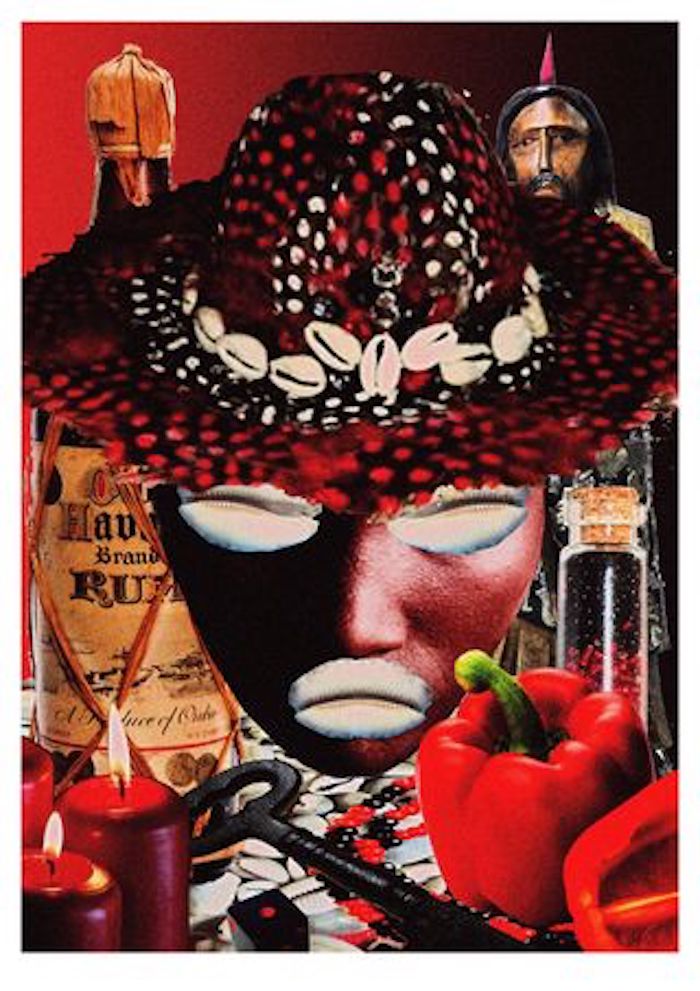

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, SUMMER 2021

THE GHOST STORY SUPERNATURAL FICTION AWARD

BY VIOLET AUGUSTINE

I didn’t notice until I saw her half naked in the yard. It was right after dawn and barely light enough to see, but she was over by that tree, pouring libations in the grass. I watched her from inside the glass. Coño, se había puesto flaca. She always had those hips, but now they were two scythes poking out the top of her slip, and her tits, just fabric where there used to be flesh.

She wasn’t always crazy. Crazy in love, maybe. When things were good, we could hear them all the way from their room, even with the doors closed, like they were right next to us. It never bothered us; she made sure I always had my pastelito de guayaba, Yemaya her blue irises and coconut, and Chango his red wine. They fucked everywhere: on the couch, the kitchen counter, on the chairs, the back stairs and in the grass. It didn’t stay that way for long. Or maybe it was long, I’m not so good at keeping time. As El Dueño De Los Caminos I always knew what was going to happen, but anyone with two eyes could see it when the frijoles got cold.

That was the first dinner she made as his wife: frijoles negros con yucca y plátano frito, the house full with the smell of bell pepper and onion, cumin and garlic and lime. Plátanos were his favorite, the green ones, crunchy and salted, double fried. He wasn’t much for sweets. She served him first, fixing his plate and taking it to the living room. He ate in front of the television, an old boxing match blaring, while she fixed herself a plate and covered it in foil. She waited patiently and as soon as he was done they’d fuck. She’d eat after he was asleep, alone and in peace, when the television screen was as black as her beans.

During the day she sewed comforters at the factory for seven dollars an hour, the kinds you’d find staged on a four-poster bed with a matching bedroom set. So her days went like that—sewing, cooking, and fucking—until one day a food truck set up outside the loading dock. She could have taken the stairs, but that wasn’t Teresita, no. Teresita did things her way. She jumped instead. Que tú eres loca, her friends said. When she landed, she felt a sharp pain in her stomach. She said it felt like she was ripping inside. Instead of empanadas for lunch, that day she just had blood. Lots and lots of blood, in the toilet at work, like a veiny chunk of red mango. She got a fever after that, but it was mild, and she treated it with diente de ajo. Her friends told her to go to the doctor. Qué carajo me puede decir un médico, she’d say. And who could argue with that.

It was a couple weeks before she felt well enough to make the frijoles, but they started up again, all over the house. This time something was different: even though her mouth made the sounds, it was like she was far away. He must have noticed too because he started staying out late. Either way, she made his frijoles: lighting the burners at a quarter to seven so they would get hot in time for him to come home. But he didn’t come home. Not that day, or the day after, so the frijoles would sit on the stove, getting colder and colder, until eventually she’d put the pot in the fridge. She’d take it back out the next night, and light the fire, just in case. But she ended up putting it right back in a few hours later. Eventually she stopped taking the pot out at all, and that’s when she started sleeping on the sofa. The beans would sit in the fridge for days until she poured them on the grass in the backyard.

He eventually did come home, but only while she was at work: she found crumbs on the counter and three stale loaves of bread. He always did that: leave the bag open. But an offering of stale bread might make it rain until the water came in through the door, so she started buying two bags of bread. And the balls on this guy: his basket was full of dirty clothes, the shirts smelling of perfume. She washed and folded the clothes, she was like that, and left them on his bed, but later she said que no aguanto el olor de violetas.

That’s when she started digging. At night, under a full moon, so I could see her out there, she would bury the corpses of cats and then dig them up a few weeks later, boiling what was left. The house would smell so bad she’d spend the whole day with the windows open cleaning with vinegar and lemon. I don’t know where she got the idea, but it wasn’t from me. I never asked for bones. She wrote messages on paper, whispering with her eyes closed. She got skinnier with every note she wrote. She’d pour oil over the paper and then sprinkle them with white powder and set the small bowls in neat rows in his closet.

She stopped cooking altogether. It got to where she only had a cup of coffee in the morning and a mango at night. They fired her at the factory when her cheeks got hollow. Maybe she got slow, or maybe it was the fabric: she’d started sewing us robes in bright colors, embroidered in silver and gold. She went to la bodega every couple days for white flowers, perfume, coconut, and soap. She stayed up all night squeezing jugo de limón. She made us crowns of purple and yellow and others of blue or white. She’d wrap bags of dried frijoles in singed fabric and place them on the door to the attic. After a month she stacked them back in the cabinet. That wasn’t my idea either, pero están jodidos, whoever eats them.

She died on a Tuesday afternoon. The mail carrier, who could see into our room because she never closed the curtains, called 911, telling the operator that she saw a woman stretched out on the floor. Her eyes were open and as clear as the sky over ocean because she kept Yemaya’s blue candles burning. Her husband wasn’t there when they took the body. He told the undertaker to burn her and he didn’t want the ashes. He didn’t call her family on the island and hired his friend’s wife to clean the house. She found bones wrapped in fabric, blood-soaked feathers and little brown spots on the wall. She thought it was devil worship and demanded more pay, and of course he wouldn’t, so she cleaned the sinks and swept the floors but closed the doors and left. It wasn’t even a week before he was moved back in with his puta smelling of what the neighbors called su peste de violeta. Soon the house started to stink. Not of violets, but of rotting flesh. Leaving a nasty message wanting his money back and searching the house for the source of the smell, he eventually found it. Por qué carajo, he yelled, pulling a putrid package of ground meat from the crawl space. Next to it was a pile of rat shit. He bought poison and placed it in bait around the foundation because he didn’t want the rats to die in the walls.

La puta sold what she could of Teresita’s stuff, but she didn’t dare sell us. She shut us up in the room with a few crumbs of bread and no one came in for a long time. All I know is that the day came when the rain didn’t stop, the wind was loud, and the thunder was louder. The windows rattled and I was sure they’d break. I heard the pump in the kitchen and the slap of wet towels. No one could leave the house for days. And that’s when I smelled them: the frijoles negros. Maybe it was the odor of bell pepper, maybe it was the notes she wrote, or the singed fabric, or maybe it was Chango, but she opened the door, dusted us off, and gave us fresh water and lit candles.

Time passed and I didn’t hear the sounds of their love anymore. I heard him call her la vieja. I heard her say ay sí, y cuando te casas conmigo? I heard his mumbles that sounded a little different every time, until it was the sound of breaking glass and then I never heard her ask again. She started spending more time in the room with us, which was fine with me. Que se joda, el come mierda, she’d say. She started up the sewing machine. She had to dust and oil it, but the tips of the needles still glinted. She bought us our bread, refreshed our wine and made the meringue. She even sewed us new robes with the bolts of bright fabric she’d found in the closet.

One day he came home from work demanding dinner. He accused her of neglecting her duties, so that night she soaked Teresita’s frijoles with part of an onion, a clove of garlic and bell pepper. When he came home from work the next day, I’m sure he smelled them before he saw them: the frijoles negros con yucca y plátano frito. He didn’t say a word, just sauntered in the kitchen like a gamecock and plopped the rice, the beans, and slapped yucca and freshly fried plátano onto his plate, sprinkling the salt with his fat fingers. He always did that: salt the food before tasting it. He sat down in front of the television, criticizing her cooking over the sound of the boxing match, demanding a cup of coffee to cut the sweet. When he was done, he clicked off the TV, left his boots where he’d dropped them, and his dirty dishes on the tray.

In the morning his boots were polished. He never said thank you. He never said a word at all. After he was asleep, she’d put the leftover pot in the refrigerator, a half-eaten mango in her hand, and every night and every morning went like this for a few months.

He died on a Wednesday, in his chair, his boots on the floor, his cup of coffee only half drunk, his cheeks hollow in the light of the TV. She told her friends that he had been sick, que no quiso decirle nada because his pride. At the funeral, lying in the casket, his skin darkened, his body dried up and shriveled, his friends commented, coño, se había puesto flaco.

___________________________________________________________

Violet Augustine is a single mom from the Cuban diaspora living in Dallas, Texas and a native practitioner of Santería/Regla de Ocha/Regla de Lukumí. She writes poems, essays, short fiction, songs, and independently produces a podcast. You can read more on her website www.adultpapers.com. “Elegua” is her first published short story.

Violet Augustine is a single mom from the Cuban diaspora living in Dallas, Texas and a native practitioner of Santería/Regla de Ocha/Regla de Lukumí. She writes poems, essays, short fiction, songs, and independently produces a podcast. You can read more on her website www.adultpapers.com. “Elegua” is her first published short story.