WINNER, Fall 2018

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

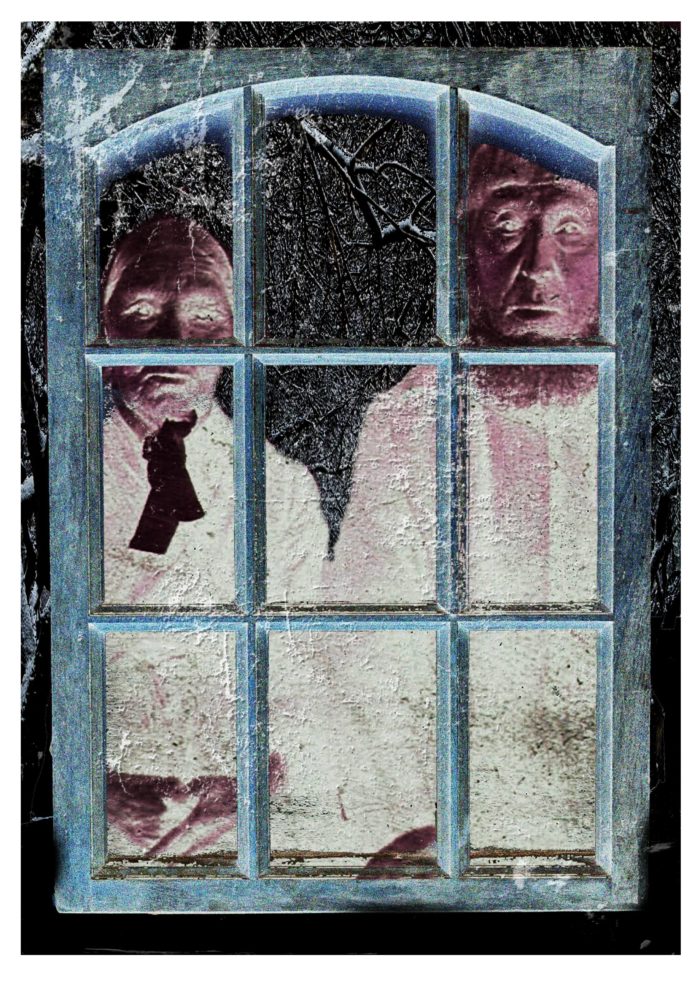

Illustration by Andy Paciorek and Edward Sheriff Curtis

Illustration by Andy Paciorek and Edward Sheriff Curtis

BY DAVID WISEMAN

NOW

“Hey Dorothy, come take a look at this.”

He is up the ladder, a litter of splintered siding and cracked cedar shingles spread on the ground beneath him. He calls to her whenever he finds anything that could be of the slightest interest, no matter how trivial. She wants the history of the place so he’s determined to bring every nail and cut mark to her attention.

“Coming.”

She indulges him because he’s so willing and enthusiastic, such a hard worker and, perhaps most importantly, requires little pay. She has put half her modest savings into buying the property, and now the other half is under pressure from the spiralling cost of renovations.

The house has been empty and unloved for nearly twenty years. Another winter, two at the most, would likely have pushed it too far: a roof leaks for just so long before something gives way and this one’s been leaking for a while. But along with as-is-where-is comes land, some of it gently sloping down to the lake and most of it kept cleared by the deer. It comes with a barn in better shape than the house and a half-mile drive through the woods, her woods now, up from the road into town. Along with as-is-where-is come dreams of back to nature and living off the land, of breathing new life into the old ways.

“Look here,” he calls down to her. “You wanted the extra window, here it is.”

“Where?” she asks, squinting up at where he’s pointing under the eaves.

“Someone had the same idea, but it’s boarded up. Look.” He outlines one side of the window frame marked by the edges of boards nailed onto it. “There’s a frame under there. Same the other side. You’ll see when I get these off.”

“What about inside?”

“Under the panels, it’ll be the same, bound to be.”

He is right. After he measures and marks the bedroom wall – fifties mail-order roses with birds of paradise – he cuts out the section. There is the window, boarded up inside as solidly as it was outside. He levers out each complaining nail, making a neat pile of the boards. A tar paper lining crumbles to fragments as he touches it.

“Dorothy,” he calls down the stairs, “Here’s that window.”

She stops her painting and runs up the stairs.

“That’s fantastic, and still got the original glass. It’s a perfect match to the other one. Sunrise over the lake, sunset through the orchard. Why would anyone want to board that up? I’m going to clean it right now.”

He’s wiped the dust and cobwebs off the outside, now she carefully does the same inside. One pane is cracked and even when she’s finished, a grey film darkens the view.

“I’m going to like this room, Nathan,” she says. She sees fresh white paint, the brass-ended bed, her books on a shelf by a seat under the window, her collection of blue glass catching early light glittering off the lake.

At the beginning of September Dorothy moves into her home. She’s been using it, room by room as the work is done, but sleeping in her caravan parked in the barn. Nathan still comes, but he has a friend who needs work done before the summer is over, so he’s down to a couple of days a week. The roof and new siding are done, essential plumbing completed, a new panel and wiring installed and she has three almost-finished rooms to live in. She’ll keep going at smaller tasks through the winter, but the next big things, a new wood stove, windows, must wait for spring and a replenished bank account.

“By the back door’ll be best, easy to get at. There’ll not be too much snow tucked in that corner,” he says when she asks about getting the wood stacked. “But get as much as you can inside, you can use the old parlour for this year, then we’ll get you a decent woodshed.”

Something else to spend on.

She’s had enough of cleaning and painting and she’s promised herself a few days to enjoy her home before the summer’s gone. Most of all she’s keen to try her window seat for more than a few minutes without jumping up to answer Nathan’s call to see a horseshoe or an old bottle he’s found.

She’s cleaned the glass more than once, but it’s still grey with age. She sits and looks across the old orchard, plenty green enough but with little fruit. The trees long ago ran out of steam, sprawling unkempt with boughs broken or leaning down to the ground. In a few years it might be different, she might bring a few back from the brink.

Through the branches she catches a hint of movement, a dark figure moving slowly. At first she thinks it must be Nathan taking a break from stacking the wood, then in alarm she thinks of bears. Maybe at apple-harvest time the orchard has been their regular haunt for generations. She runs downstairs to get a better look and warn Nathan.

Together they listen and look but there is no sign of bear or any other creature. Nathan thanks her and tells her to be careful. That night she studies a booklet from the local history society which has maps of the district at different times since it was first settled by Europeans. The first mention of her property is 1888. Next to the black dot denoting the house is the name Wm. Baxter.

On her third day of rest Dorothy rises early, prompted by the dawn light streaming through her lake-view window. It catches her blue bottles exactly as she had hoped. She plans to walk across the meadow to the water’s edge where she’ll sit and absorb the wonderful tranquility of this place. Her place, she reminds herself with a smile. She glances out of the orchard window, checking for animals as much as anything, and is surprised to see a woman, hands on hips, standing with her back to the house. The figure is indistinct and Dorothy reaches automatically to clear the glass with a wipe, but the grime is ingrained and the ripples subtly distort the view. Dorothy’s delighted to see her first real visitor, even if it is a little early in the day. A curious neighbour no doubt, come to offer a welcome. Are there Amish nearby? The woman’s long dark skirt, white apron and cap suggest a sect of some kind.

When Dorothy steps outside she can see nobody; there’s no car on the drive, no neighbour bearing a welcoming pie. She calls out as she walks round the house to be sure, and ventures a little way into the orchard before disturbing a porcupine. She retreats slowly to the house. Perhaps the woman had been waiting a while and got fed up. Dorothy takes coffee to the lake shore but cannot settle for more than a few minutes.

By the end of the month Nathan has finished all Dorothy has asked him to do. He’ll be back in the spring for renovation season and he’s agreed to plough out the drive once the snow sets in. She’ll have no need to call, he’ll just come and do it, not that there’s much phone signal near the house. She should get her own plough, but not before she gets a new stove, he tells her.

Nathan has been invaluable, a godsend she says, and good company despite his excitement at every scratch of history he’s uncovered. Dorothy invites him for supper as a thank-you for his work and is slightly surprised when he quickly accepts. He’s twenty years her junior and she’d imagined he’d have better things to do.

After eating they walk together round the house, taking in all the improvements he’s made and talking of those still to come. The newly exposed window is the only real change, everything else has been replace and repair. Next year, or the year after, she’ll get him to take it out and put in a modern unit.

“It’ll be a shame to lose that old glass,” he says. “We’ll keep that, someone will want it. Same with all the old windows.” When Dorothy looks sceptical he adds, “You’d be surprised, there’s always someone wants old windows.”

“I had a visitor, did I tell you?” she asks him. “A woman, dressed like the Amish, she was standing right where we are now, gazing up through the orchard.”

“Yeah? Who was that? There’s no Amish round here.”

“She didn’t stay. When I came down she’d gone.”

Back inside, Dorothy’s keen to show him her bedroom, especially as it’s flooded with the last of the evening sun. It’s his turn to look sceptical.

“Nathan! It’s all right, I promise I’ll be gentle with you,” she smiles and leads the way up the narrow stairs.

“You’ve done it nice. We’ll get these windows out next year, easy, no mess.”

She is drawn to the orchard window and looks down, squinting into the sunset. The long-skirted woman is back, but not alone. A man is standing beside her. Together, they are staring up at Dorothy. He is bearded, shirt-sleeved, and holding a broad-brimmed hat in his hand.

“She’s back,” Dorothy says softly. “The Amish woman.”

Nathan steps close behind her, peering over her shoulder.

“I don’t know ’em, they’re not from around here.”

“I’ll go down,” she says, then suddenly uneasy, “Come with me?”

She follows him down. As they pass by the parlour window they see no one waiting outside and when they open the door the yard is empty. Just as Dorothy did previously, they circle the house, carefully scan the meadow and peer through the orchard.

“Come on!” Nathan yells and jumps into his pickup. He spins it round and they hurtle down the drive. They haven’t gone far before they know they won’t find anybody but he drives the length of it. It’s a straight stretch where the drive comes out but there’s nothing moving, no plume of dust hanging along the dirt road. Carefully he drives back to the house. The woods are closing in now the sun is down. Peer as they might, they won’t see anything.

“What happened?” Dorothy says. “What did we see?”

They tell each other what they saw although really they didn’t see much and when they think about it they agree it was no more than a glimpse, a few seconds, five at most. It’s impossible to be sure what they saw.

Even so.

“You’ll be all right?” he asks, knowing in a minute or two he’ll be back down the drive and away from the place.

“Yes,” she answers confidently. And she is confident; she feels no threat, only deep puzzlement. “I’ll be fine. Thanks for everything Nathan.”

“I’ll come by in a few days.”

She waves as his truck is swallowed by the darkening trees. In a few seconds she is alone in the gloom. A breeze gets up. There are spits of rain in the air by the time she gets indoors. It won’t be long before she’ll need to get a fire going.

A few days pass without Dorothy seeing anybody, no visitors of any kind, Amish or otherwise. She wonders if she is avoiding looking through the orchard window. Even as she thinks it, she catches herself glancing away. Ridiculous, she decides, she’ll bring her morning coffee back upstairs and sit by the window and see what there is to be seen.

She’s hardly taken the first sip before a movement catches her eye. When she looks there is no movement, but the two figures have returned. The man is lying face up, the woman is crouched beside him. Near his feet is a ladder, broad at one end, tapering narrow at the other. They are a tableau. Dorothy studies them as best she can through the distorting glass, determined to know more about them than the few seconds of previous encounters. There is little to be learned. The woman has a bonnet over her fair hair, a dark green dress hides her figure from neck to ankle. The man she stoops over scarcely has anything more to show: dark clothes and heavy lace-up boots, working boots. One leg is splayed out awkwardly. He has a full head of black hair and although the woman obscures her view, Dorothy recognises the black beard.

She waits a few seconds, then more, testing how long the vision—she is sure it is a vision—will remain. Slowly she shifts from side to side, changing the angle of view by a few inches at a time. The couple remain in sight. A sudden squall of rain spatters the window. As it runs off Dorothy’s visitors have dissolved with the water.

She rushes down. If they’re real there will be marks on the soft ground, there will be a trace of the man’s outline, drier where he covered the earth. No marks, no dry patch, no rain. She looks up at her window. Her red coffee mug is where she left it on the sill. She could call out, search for traces, but no one would answer; she’d find nothing, of that she’s sure.

A couple of days later Nathan drops in. “You seen those folks again?” he asks.

Dorothy is tempted to say no. He’s probably told a few people already and she has no wish to become the crazy woman in the old Baxter house. She doesn’t want people nudging each other when she goes into town for groceries. But Nathan has shared one of the visions with her.

“Hmm, yes, on and off. Just glimpses, you know,” she says vaguely.

He nods.

“I thought I’d do some research on the house, who’s lived here, just to see if there’s anything. Maybe you could ask around a little?” she says, then adds quickly, “If you like.”

He doesn’t commit one way or the other.

“You had the stove goin’ yet?”

“No, but soon.”

In a few minutes he is gone, duty done, uneasy to be there.

For a few days Dorothy tries a new tactic. She spends as much time as she can sitting at the orchard window, to see how often there is a vision, to see what else she can learn of the man and the woman. Only once does she see anything. The man is standing looking up at the window, soundlessly shouting and waving his arms as if to attract her attention. It is night, or dusk, and his features are illuminated by a flickering light from a candle or lantern, although she can see neither. The woman is by his side, kneeling, head down, as if she is a supplicant at the altar rail. It is the first time she has seen real movement in either of them. The movement makes her uncomfortable. While they appeared as a still-life they were a strange anomaly, but moving, that’s different. If they could move they could go anywhere.

A few days later, having seen nothing more and not wishing to see more, Dorothy hangs a length of black velvet across the window. The nights are drawing in, she will miss no golden sunsets across the orchard, and besides, she prefers her privacy, whether from the eyes of curious coyotes or bearded visions.

The following morning she’s just dressed when she hears a truck and the familiar beep-beep announcing Nathan’s arrival. She draws back the velvet and recoils in terror. For an instant the bearded man is right there, like a great bird spread against the window, his mouth open in a cry, his eyes wide in horror. She falls backwards dragging the velvet from it’s pinning. It covers her like a dark shroud. She thrashes and screams until she frees herself.

“Dorothy? Are you all right? Shall I come up? Dorothy?” Nathan is calling up the stairs.

She tries to compose herself but is still breathless and shaky as she goes down to him.

“You look . . . here, sit . . . can I . . . ” his voice trails off.

“He was at the window,” she says stiffly. “You were there, out there, did you see . . . ?”

He shakes his head.

“Standing in the yard, that’s okay. At the window, like that, that’s not okay.”

They are silent for a while, then Dorothy collects herself. Some colour returns to her face and her breathing settles.

“Hello Nathan, good morning. How are you today?”

“I’m okay. There’s snow on the way, tonight maybe. Might not be much. Anyway, I thought you should know.”

“Thanks.”

In the late afternoon Dorothy enters her bedroom and looks cautiously at an angle through the orchard window. She sees her yard, the orchard, the fading light, nothing more. She gathers up the velvet and tacks it firmly in place, this time with no easy option of pulling it aside.

In the evening she eats by her roaring stove, the house filling with the smells of burning wood. It’s an evening to sit with a bottle of wine and enjoy being snug in her home. A night to sleep soundly in blue flannel pyjamas as the first flakes of winter drift down, spitting steam off the red-hot chimney.

THEN

“Better than I thought it’d be,” he calls down to her.

She is taking the little sacks of apples as he passes them down and carefully packing them in the wooden boxes she has on the dolly. It is their first proper harvest, six years since they put the trees in. They’ve added to them each year, carefully grafting a dozen or so each spring. In another six years they’ll need help to get the crop in. For now they’re happy their venture is thriving.

“It’s wonderful, William. And there’s hay in the barn and food on the table. We are blessed.”

She is thinking of more than the food. She has a secret, a happy secret that she has yet to share with her husband. Seven years of marriage and finally they’ll have a baby to show for it. She’s hugged the knowledge to herself, at first so she could be sure, then waiting for the right time.

They are tired from another day’s labour when they sink into their bed. The last of the light is still in the sky as they lie together and watch through the square of window as the stars come out. It is her moment.

“William,” she says softly, “in spring there’ll be another mouth to feed, God willing.”

He sits up on his elbow, leaning over her. “Amy, you’re sure?”

“Yes.”

He is overjoyed and falls on her, kissing her face and stroking her hair. Blessed, she had said, and surely they are.

“We’re ready.”

In the morning he insists that she take time off from the orchard, to save her strength he says. She wants to please him so she agrees. She’ll find plenty to do in the house. He works in the orchard, picking and packing a little more fruit, then scything grass and repairing the deer fence. All the while he keeps a lookout for her and sees her at the bedroom window, her bonnet off and her hair hanging loose. He waves but she is head down, reading her Bible most likely. He said to take a day’s rest and she is. There’ll be a long road ahead and he’s happy to see her settled and quiet. A baby! He can’t quite believe it.

When she calls him for his lunch he’s at the kitchen table in no time. They sit together with a loaf still warm from the oven. They’re still smiling at the prospect of a family.

“Good to see you resting up this morning, Amy,” he says. “I don’t know how you found time to bake.”

“How d’you mean? I’ve been in the kitchen all morning, although true enough, I sat a couple of times.”

“I thought you were up in the room. By the window, reading.”

It doesn’t matter, they don’t argue, they rarely do, and not today of all days. The light plays tricks and it is the season for mists to roll up from the lake in slow rising spirals. A few mornings later he thinks of that again as he’s in the yard and looks up, attracted by a glittering blue thrown up on the ceiling of their bedroom. The fractured light reminds him of a kaleidoscope, less regular but fantastic in its variations. It seems a shadow passes across the projection and he calls his wife. He expects her at the window but she comes from the kitchen.

“William?”

“Look,” he says, pointing, “look at the light.”

“Off the lake,” she says.

“I’m sure, but the colour, so blue. And look there, a shadow moving.”

She considers for a moment.

“The horses are down at the water.”

A week passes, a happy week, an abundant week as the community celebrates a good harvest and joyfully shares William and Amy’s news of a baby. The summer lingers in warm days and calm nights. They have their wood cut and stacked, the barn is full, the chickens are laying.

On a Tuesday after supper William walks out down to the lake and looks back at his house, a darkening shape against the brilliant evening sky. Somewhere inside Amy is attending to the last chores of the day. He meanders across the meadow, all the sounds and scents of the land enfolding him, until he hears her calling, sudden and urgent. He quickens his pace as she calls again, then he breaks into a run.

He finds her at the bottom of the orchard, shouting for him, thinking he’s up there. When she turns he sees the fear on her face and she seizes him fiercely.

“William, there’s people in the house!”

“People? Who?”

“In our room, look.”

A woman’s figure is framed in the window, silhouetted by bright light. Behind her, another’s movement casts shadows.

He stands, gaping, astonished, torn between comforting his wife and investigating the intruders. “Wait here,” he says after a few moments. “I’ll see what this is.”

But she holds him tightly. “No,” she insists.

Abruptly, the light they see in the room is extinguished. In its place the window reflects a dim imitation of the deepening sunset.

“Come, we’ll go in together,” he says.

Their house feels as it should. They light a lamp and climb the narrow stairs. He’s tempted to call out but knows it would unsettle her. Their room is as they left it, no bright light, no figures or presences. As he sets the lamp on the nightstand, she imagines how she looks now exactly as the intruder had looked to them as they stood in the yard. For a fearful moment she wonders if time has twisted and she’s seen herself.

“Another trick of the light?” he asks, half to his wife, half to himself.

“What else?” she says a little shakily.

“We built this place, every stick of it, my father and brothers, we know there’s nothing here. And good new wood, nothing used went into it. There’s no spirits in this house.”

She wants to ask him if it can be herself she’s seen. Instead, she picks up her Bible from beside the bed with trembling fingers.

“The Good Book has been here all along. We’ve come to no harm.” In a moment of sudden concern she puts a hand to her belly but feels nothing is amiss. “We’ve come to no harm,” she repeats.

The episode hangs over them as a cloud, although they feel no immediate threat and are uncertain of what they really saw. They don’t mention it to anyone and they don’t mention it to each other. Amy doesn’t include it in her prayers, either. As days pass the event becomes less real, something that might have happened to someone else. Each day without a new sighting pushes the intruders further away.

Then one night in the small hours before the first streaks of dawn are in the sky, Amy wakes, fearful, sweating. She sits on the bed and tries to shake the demons from her head—not that she knows their form or shape. Their substance has evaporated leaving only a residue of terror.

“Amy, what is it?”

“I don’t know,” she wails, “we must get up, get out.”

He lights the lamp and guides her down the stairs. She is for getting outside as quickly as possible, but he stops her.

“No, it’s cold, here, your coat.”

He puts it round her shoulders before she scuttles out.

The night is silent, black, cool. He holds up the lamp to their white faces, quick breaths hanging in the air between them.

“Better?” he says.

“Yes,” she nods, “Thank you William.”

“Let’s calm ourselves before we go back to our bed. Come, we’ll walk a little, once, twice round the house.”

A noise from somewhere in the orchard takes their attention and they strain to listen for a repeat but none comes. When they turn back to the house the window to their bedroom is alive with raging fire, orange and yellow flames, intense, frightening. What providence has let them escape? Amy falls on her knees to give thanks to her God for deliverance while William stands in wonder.

Why is there no smoke, no crackle of timbers, no sparks leaping high in the air?

He lays the lamp on the ground behind them to be sure of what he’s seeing without the flicker of light in his hand. In the instant of taking his eyes from the window, the fire is gone.

“Amy,” he says gently, laying a hand on his wife’s shoulder. “Your prayers are answered.” She looks up, tears streaming down her face.

“What is this William? Miracles or the Devil himself?”

“Neither, I think. It’ll come clear.” Not that he believes what he says.

“I can’t go back, I’ll be too afraid,” she says.

“No, not tonight. It’ll feel different in the light, it’ll be our home again, you’ll see. This will be no more than a bad dream. Maybe that’s what it is. We’ll make a soft bed in the barn and sleep safe and sound in there. We’ll see what’s to be done in the light of day.”

They sleep, fitfully, for a few hours before the sun is up. William, practical, sensible, reasons that the longer they lie in the hay the more they’ll reflect on why they are there. He leads the way into the house and immediately up to their room. Grasp the nettle, better now than to let the fear take hold again.

It is as he expects: their unmade bed as they left it, the sun glittering off the lake through the mist swirls on the surface. Looking across the orchard they see the work they’ve done, and a section of fence still to be fixed.

“Here’s what might be happening,” he says slowly, sitting on the bed and patting for her to sit beside him.

She looks expectantly at him, urgently hoping his reasoning will banish their troubles.

“When we first saw something, a figure, a shape, shadows moving, we thought it was the light off the lake, reflections, and we were making something out of what was nothing. Maybe that seed has lodged in our heads and now we’re making more of it all. And your nightmare last night, that played right into it. By the time we were outside in the dark we were both ready to believe something was going to show itself. Maybe we just fooled ourselves, frightened ourselves into it. Maybe we were still part asleep.”

She wants to be convinced, for what he says to explain everything. Their room looks right enough, it feels right. Her eyes are taken to the orchard window.

“Look at the glass, William. It’s all smoky.”

He goes to the window and studies the pane. It’s true, there’s a hint of grey about it that he hasn’t noticed before. When he wipes his wet finger across it nothing comes off. He looks at the mark he’s made and then at Amy.

“I don’t suppose that’s made it any better,” he says straight-faced, then grins and pushes her back on the bed so they both laugh and kiss.

“Come on,” he says, “let’s get breakfast and do something with this day. But here’s a promise, Amy. If you see anything more, or I do, then I’ll close up the window. I’ll even close up this room if you like and we’ll make our room over the parlour. I’ll put a window in there and make it so it’s perfect for us. And our family.”

As the nights grow colder and the days grow shorter the forest around them puts on its red and gold fire show. William and Amy pick up their rhythm again, although it’s subtly changing as the weeks pass and their baby grows. With no further events or sightings it’s possible to believe there will never be anything further.

Until the third week of November.

It is late in the day when William returns from closing up the chickens in the barn. The grey gloom is rapidly deepening and he’s looking forward to a warm fire and supper at the kitchen table. As he walks below their bedroom window some extra sense makes him look up. She is there again. There’s no mistaking her for Amy, not this time. She’s dressed in blue pyjamas and is hammering on the window frame, her mouth wide in a scream. Orange smoke billows behind her. He stands back to get a better view, to see if he can’t get a better understanding of this apparition. Then she is gone, leaving only the smoke. A moment later that is also gone, only the black, blind window looking out on their orchard and on him gazing up at it.

“William? What is it?” she asks the moment he has his boots off.

“Nothing. It were nothing at all,” he lies. She is not deceived.

“That woman? Is she back?”

He nods.

“At the window again? What this time?” She puts the dish she’s holding back on the stove and sits heavily, her arms spread across the table to him.

“Just standing, looking. I don’t feel she means any harm,” he adds, to deflect her from his new lie.

“Oh William,” she cries, reaching for his comforting touch.

“I know what I promised you. Too late now, but I’ll do it in the morning, inside and out. We’ll try that and see how it works for us. I’ll make a proper job of it.”

All night they toss and turn, in and out of sleep, their fears undefined and all the worse for being so.

As soon as it’s light he’s for getting out into the freezing mist to get started but Amy says to wait. “Not before I put something warming inside you.”

While she’s making breakfast he measures the frame, pulls some planks from the wood loft and sets up a trestle to cut them.

Then they sit together and burn their tongues on the porridge, laughing nervously at their foolishness, confident they have the solution to their problem. The view over their orchard is a small sacrifice to make.

He cuts the lengths, eight for each side. “Inside first,” he says. “I’ll move your things.”

“I love you William Baxter.”

He works carefully and cleanly, moving her hairbrush, comb and mirror from the nightstand. To be sure no light penetrates, he tacks tar paper over the window before nailing the boards in place. The fit is perfect; they cover the frame exactly, butting up against the wall. With the early morning light streaming in from over the lake their room seems hardly less bright than before.

In the yard he looks up at the satisfyingly darkened window. He fetches the tallest of his orchard ladders from the barn and checks the hammer and nails in his work belt. He’ll take up one length at a time, there’s no rush.

At the top of the ladder he balances himself before raising the top board into position above his head. It’s going to fit as neatly as those inside. He has one hand on the board and the hammer raised in the other when the tar paper and planks are swept aside as if they are no more than a curtain. The woman is there, right in his face, as horrified as he is. He recoils from the phantom, falling backward, one foot caught under a rung. He twists in his fall, trying to save himself but he lands head first, snapping his neck.

William’s eyes are open when Amy reaches him. She imagines he is no more than bruised and stunned until she cradles his flopping head in her hands. Then she falls on him, kissing his brow and whispering his name. She looks up suddenly, feeling she is being watched, but the window is blank.

David Wiseman lived in the UK for most of his life, but is now a resident of British Columbia, Canada, where he writes and occasionally appears as a background actor in movies. He writes long and short fiction, is an occasional blogger, and enjoys maps, photography, travel, and reading and is also an accomplished genealogist. He tends to write short stories as a relief from writing longer ones. “The reward of finishing comes a lot sooner,” he says. “I write slowly, so my novels take a year or two. With a short story I get the buzz of completion after a couple of weeks. ‘Double Aspect’ is a favourite, a story which revealed itself wonderfully as I wrote it for The Ghost Story in August this year.” David’s novels are currently published by Askance in the UK under his more formal DJ Wiseman name. A Habit of Dying, The Death of Tommy Quick and Other Lies, and The Subtle Thief of Youth will hopefully be followed in 2019 by a fourth, presently in the final stages of editing.

David Wiseman lived in the UK for most of his life, but is now a resident of British Columbia, Canada, where he writes and occasionally appears as a background actor in movies. He writes long and short fiction, is an occasional blogger, and enjoys maps, photography, travel, and reading and is also an accomplished genealogist. He tends to write short stories as a relief from writing longer ones. “The reward of finishing comes a lot sooner,” he says. “I write slowly, so my novels take a year or two. With a short story I get the buzz of completion after a couple of weeks. ‘Double Aspect’ is a favourite, a story which revealed itself wonderfully as I wrote it for The Ghost Story in August this year.” David’s novels are currently published by Askance in the UK under his more formal DJ Wiseman name. A Habit of Dying, The Death of Tommy Quick and Other Lies, and The Subtle Thief of Youth will hopefully be followed in 2019 by a fourth, presently in the final stages of editing.