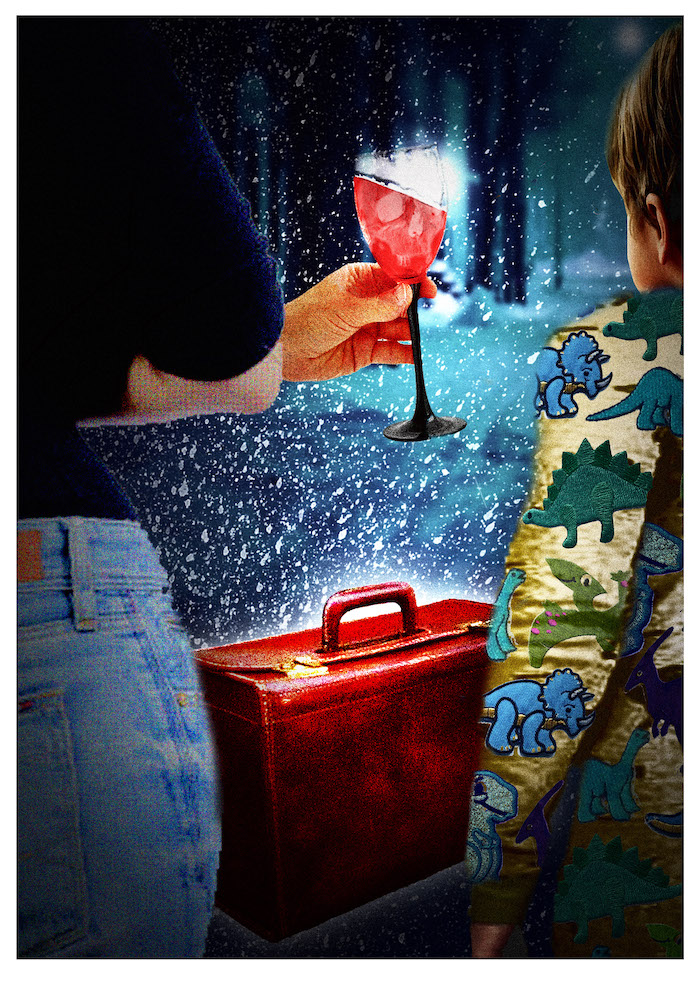

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, Spring 2023

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY RUTH SCHEMMEL

“Hey there, I’m not here to sell you anything. . . .”

The salesman sticks a foot in the door before Abby can close it. Why, she thinks, did I open the door in the first place?

“You like security, am I right? You like to know there’s an alarm system in your house, to protect the little ones. Am I right?”

“I don’t have little ones,” Abby says. “I’m the babysitter?”

“But that’s exactly why you do need an alarm system!”

“That doesn’t make sense,” she says. “Are you listening to yourself? I can’t buy anything for this house.”

“You know what?” says the salesman. “I don’t think you qualify for this sale, anyway. I’ll have to check with my office. But maybe? I’ll have to see.”

“Great,” she says. “Fine. I don’t care. Because I’m not buying anything from you.”

“Just say yes,” he says. “To anything.” His eyes implore her, pouches beneath them the color of bruise. He reminds her of her father before the end, his small electronics store failing, bankruptcy imminent, still putting on the false smile, trying to believe. Tears flood her eyes. But it isn’t her father, of course, not quite. His face is rubbery, slack, somehow inexact. She smells his desperation: fresh underarm sweat in unwashed clothes. He looms in the doorway, his shoes—scuffed wing-tipped oxfords, brown and white, once-beautiful shoes of a bygone era—hanging half over the threshold. He can’t come in, she notices. Maybe he can’t.

“No,” she says.

“Do you like blue skies? Do you like rainbows?”

“No.”

“Do you like apricots? Is today Thursday?”

“No.”

“It is, though. You know it is!”

“No.”

“Do you want me to go? Do you want me to leave you?”

“Yes!”

“Thank you!” His words are a gasp, a chuff of air. That’s all he is now: air. For a shimmery moment she can see through him, see through his saggy cheeks to the clumps of white snow falling behind, lit by streetlamps, plopping onto the asphalt and disappearing. And then, as a swell of wet cold air washes over her, he’s gone. Across the street a neighbor man slams the door of a pickup. Soft light pools from his open garage. He’s hoisting a box of tools from the cab when he looks up, catches her eye. He’s the sort of specimen she’s learned to be wary of. A husband and father. A family man.

The sort of specimen who’s taken everything she’s ever had.

Correction: the sort of specimen who was the rocky outcropping to her storm-tossed sea vessel. The sort of specimen she once smashed herself against, ruining everything for everyone forever.

Not that her particular specimen, her particular rocky outcropping, would look at her now.

She closes the door.

Phil Philbrick, ten, standing in the living room behind Abby in his dinosaur pajamas, scowls at her with suspicion.

“What are you doing?” he says.

“Just looking at the snow. It’s snowing. Did you see?”

“Who was that man? Why are you crying?”

Who was that man? The question haunts her all the next day. Your neighbor, she’d told the kid, thinking he’d meant the brawny blue-collar beauty with the toolbox across the street. No, he’d said. I’ve never seen him before. That’s when she realized the kid—Phil Philbrick—saw her salesman. She’d figured they were figments, the twenty or so traveling salesmen who’ve been dropping by during her babysitting gigs, some seedy, some sexy, all desperate, trying to sell her things she doesn’t want for a house she’ll never own. They were just productions, she’d thought, of her own brain, which she herself damaged and chemically abused. This was just another part of the living hell she’s cooked up for herself, her own self-loathing personified and embodied, encased, momentarily, in flesh.

But Phil Philbrick seeing the salesman changes the equation. It means there was actually a salesman there for him to see. For a moment there was.

Could it have been an actual ghost?

Then she thinks: of course! Of course she’s screwed up her life enough to drag an embarrassing string of loser ghosts around. Of course she, Abby Glickman, is the one living mortal who’s managed to gash the ghostly veil, upheld, she can only assume, for millennia. Till now! The whiff of her failure must be pungent enough to waft through the afterlife. Why her ghosts aren’t alcoholic drug addicts who’ve slept with the wrong people, failed fired schoolteachers who’ve addled their brains and ruined their teeth, lost their families, alienated friends—ghosts, in short, more like herself—is anyone’s guess. Let it be salesmen. Huzzah!

It’s in this spirit—the spirit of huzzah—that she flings the door open the next night, in the home of Laura Kosishche, deep in a Benadryl-assisted sleep.

“Two words,” says the salesman, a younger, hotter version of the dude from the day before. He lifts up two hands as if placing the words on a marquee. “Solar panels.”

“One word,” says Abby Glickman. “No way.”

“Well, that’s two words,” the salesman says with a sexy chuckle.

“You can count. What else can you do?”

She hears the innuendo in her voice. She starts to smile and, catching herself, closes her lips. She’s flirting, she realizes. With a ghost.

Well, this is a new low, her bossy inner voice begins. We’re this starved for the male gaze that we’ll take it from a wraith? A possibly malevolent, possibly soul-stealing scrap of a being, obviously unhappy or why would he be here?, unable to maintain a fleshly presence for more than a few moments? Pret-ty hard-up, Abby Glickman.

Oh, but this boy’s blue eyes! Otherwordly they are. Transporting. I’ll take care of you, his eyes promise. I’ll keep you safe. You’re all that I desire. He takes off his hat. “May I,” he says, sliding next to her in the doorway, “come in?”

She starts to feel—in his blue gaze—lovely.

You can do whatever you want, you handsome stranger, she could say.

And why not? a voice she hasn’t heard before in her head reasons. It’s not like he’s real. Doesn’t it feel nice to be desired? Best act fast, before he winks away!

She finds herself smiling, an open-lipped smile. Then, remembering her unrepaired teeth, she closes her lips.

Tenderness comes into his gaze. Pain on her behalf, for her lost looks, lost youth, lost chances? He touches her face, tucks a strand of hair behind her ear. “Can I hold you? Just for a moment?”

He draws her into his arms. His lips find her lips.

She feels a wrenching tug from the bottom of her abdomen, like the pulling up of a stitch. Her body shudders with pleasure.

Not pleasure, exactly, she thinks. He’s . . . drinking me!

She shoves him back against the door frame. “Get out!”

Surprise flashes on his face. Anger.

For a second she feels her lips wrenched back crudely, as if by an invisible dental assistant, exposing her gums and ruined teeth. Her hands fly to her cheeks. She can’t control it, can’t stop the ghastly grin.

“You have such a beautiful smile,” he says.

“uck ooo,” she says liplessly. She grabs him with both hands, shoves him off the stoop. “Oo ucking agh-hole!”

“You—” His face twists with bitterness. Before he can finish he’s disappeared.

She pats the life back into her numbed cheeks.

Lessons learned.

“So you were a teacher?” Phil Philbrick asks her. A week has passed. A week without work. She’d feared this was it—her clients had picked up on her desperation. Maybe the ghosts had blown it for her. Neighbors might have seen things, made calls. But then Phil Philbrick’s mother had texted—and just in time, with February rent so nearly due.

“A lifetime ago.”

“Why’d you quit?”

An image flashes in her mind: herself, lying under her desk in her free period, weeping. That was toward the end, as it was all falling apart. Her marriage, her job. I couldn’t do it anymore, she could say to the boy. I couldn’t pretend to have anything to give.

I prefer this, she’s always said before, when asked. I love babysitting. Visiting kids at their homes. . . . But Phil Philbrick has seen her ghost. Phil Philbrick knows she’s being haunted and hasn’t told his mother. She owes Phil Philbrick some version of the truth.

Or maybe it’s the glass of wine she’s poured herself that makes it easier to be honest. Wine because why not? She’s a babysitter, not a brain surgeon. A person’s got to still her nerves somehow.

“I lost the job. I made mistakes.”

“What kind of mistakes?”

She shakes her head.

“Is that why you’re being haunted?”

He’d sat himself down in a heap on the carpet, his bare feet knobby and raw. He’s a long, homely boy, too smart and sensitive by far. Too sweet. Too old to be wearing dinosaur pajamas, as he is again this night. He’ll suffer terribly through adolescence, she thinks.

Maybe he’ll become like her.

Maybe he’ll suffer from anxiety, alienate people, obsess about them, use them like drugs. Use sex. Maybe he’ll start a family and wreck it, he’ll succumb to destruction in any of its tempting forms. Maybe a needle or a pill. And he’ll fall. He’ll fall so far and so hard that his old ordinary life will seem like a heaven he’s lost, an Eden.

God, how he’ll wish himself back.

“I don’t think I’m haunted anymore,” she says.

She believes it. The secret is not to want. Anything. That’s the lesson she’s been absorbing, the lesson that’s finally sunk in. As long as she wants nothing, cares for and about nothing, nothing in the world can touch her. That’s all the salesmen can do: make her think she wants something. I defy you, she wills the ghosts silently in her heart, to find anything that can tempt me.

Just then there’s a knock on the door.

“Go to bed, Philip.”

“I want to watch.”

“Bed.” She waits until he’s safely in his room to open the door.

“What a beautiful evening! What luck to find you home,” says the salesperson, in a striking, smoke-ravaged voice. It’s a woman this time, a good ten years older than Abby. Maybe twenty. There’s a jarring disconnect between her eyes and the rest of her face. Her eyes are those of an accident victim, possibly a murder: wide open, shocked and staring. It’s like they’ve seen—are seeing—horror. Yet her features are calm, her face neatly made up. A smile splits her face, ear to ear. Her hair falls in a dyed black shag to her chin.

It throws her. Abby is prepared for the broken old men with sad eyes. She’s prepared for hungry sharks and their flattery. She’ll never believe their lies again! But a woman is something else again. Who in her life has ever hurt her like women?

“May I come in?” the woman says. “It’s cold out here. Brrr.” She doesn’t wait: she just enters.

Well, that was a mistake, Abby thinks. How did I let that happen?

Tell her to leave, her inner voice urges.

“I won’t be buying anything,” she hears herself say. “I don’t live here, you know.”

Leave. Leave. Tell her to leave.

“Would you like some tea for the road?”

“Tea?” The woman looks pointedly at Abby’s wine glass. “If by ‘tea’ you mean ‘wine,’ then hell, yes.”

The woman has a shambling lopsided walk, as if her body had been broken apart and hastily reassembled. She’s sitting on the sofa when Abby returns with another wine glass. The staring horror of her eyes contrasts with her too-wide smile. “Thank you. Now that’s a generous pour. To Bacchus!” She holds up her glass.

They drink.

Only then does Abby’s gaze settle on the flat, rectangular leather case propped on the woman’s knees. The woman opens the latch.

“I told you I’m not buying anything.”

“Yes, yes.” The woman waves a gnarled hand, the fingers twisted with age, her nails painted a lovely deep red. “Well, there’s no harm in looking, is there?”

Abby finds she can’t argue with this. There is harm in looking, of course. Ask any addict. But this woman muddles her thinking, slows her tongue. Or maybe that’s the wine. The wine, of course. She’d gone months without it, till now. But it doesn’t matter: there’s nothing in the world she wants.

“Are you real?” Abby blurts at last. The woman seems fully embodied for a ghost. But then they all have been, all of her ghostly salesmen. For a minute, anyway. This woman’s presence seems more solid than the others. She’s also in no hurry. She doesn’t seem to be in danger of winking away, as the others have done.

“Am I real?” She lets out a throaty laugh. “Oh, my dear. What a charming question. You’re a treasure.”

Abby blushes. She feels that she is a treasure. Right now she feels she is. “So what are we looking at here?” she asks, suddenly bashful, eager to direct attention away from herself.

“What are we looking at here? We are looking,” the woman says, “at your heart’s desire.”

What they’re looking at is knives. Kitchen knives. Five of them, a gleaming set, nestled in crushed blue velvet.

“This isn’t my heart’s desire,” Abby says. But she wonders.

“Oh, really?” says the woman, her voice a soft rasp. “Then tell me: what is?”

Peace, Abby thinks. Numbness. An end to pain. She looks up at the woman’s horrified eyes and placid smile, and understands. “You’re a suicide,” she says.

“Now, that’s not polite.”

“I can’t afford these.”

“I think you can.”

“I don’t have money.”

“No,” says the woman. “You don’t.” She smiles her disturbing smile.

“You’re saying I don’t need money.”

“I’m saying you don’t need money,” the woman says, “for this. But there’s a cost.”

Abby stares into the woman’s shocked eyes. Only this—only the woman’s look of frozen horror—stops her from saying the thing she wants to say.

The thing she wants to say is yes.

She feels it again: the tugging from the bottom of her abdomen. The slipping of herself out of herself.

Oh, she thinks. To be free. To be finished.

“You don’t have to keep going,” the woman says, her voice now crooning. “You’ve done what you could. You had a good run. You did! It’s okay to take your foot off the gas.”

“My foot off the . . .”

A sound on the stairs breaks her concentration. Phil Philbrick in his dinosaur pajamas. Phil Philbrick, with the terrible future she’s imagined for him. His lonely adolescence, his descent into addiction.

His possible descent. She shouldn’t get ahead of herself.

If she completes this sale here—if her fingers close around the handle of a knife—will he find her dead body?

No, she’s about to tell the woman, but the woman is busy cutting her own throat. She’s gone before the blood hits the carpet.

I’m not the ghost, she thinks later, after she’s put Phil to bed. She wanders into the kitchen, runs her hands over gleaming appliances. Things she’ll never own. On the refrigerator there’s a photo of Phil’s parents, Bill and Donna. She kisses the image of Phil’s dad. Then, why not? She kisses the image of Donna. She pours herself another glass of wine. She has plenty of love left. She has plenty of love left for the world.

___________________________________________________________

Ruth Schemmel’s work has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, Fiction, New Orleans Review, and North Dakota Quarterly. She has received a Jack Straw Writers Program fellowship. A former Peace Corps volunteer and current community college instructor, she has taught English learners in Ukraine, the Bronx, and the greater Seattle area, where she lives with her family. Author photo: Look Photography, Monica Schippers

Ruth Schemmel’s work has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, Fiction, New Orleans Review, and North Dakota Quarterly. She has received a Jack Straw Writers Program fellowship. A former Peace Corps volunteer and current community college instructor, she has taught English learners in Ukraine, the Bronx, and the greater Seattle area, where she lives with her family. Author photo: Look Photography, Monica Schippers