WINNER, Spring 2022

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY TREANOR WOOTEN BARING

The Natchez cotillion spring dance drags on well after two. While Katherine and her friends chat in the kitchen, Jack joins the other hapless dates slumped in chairs against the wall. The young men now openly take drags of whiskey from silver flasks. The hired help cleans up around them.

In the parking lot, Katherine and Jack kiss hungrily by his Chevrolet Bel Air, drawing whistles from the others. On the ride back to Wetherbye Plantation, Katherine falls asleep, her head on Jack’s shoulder, her silver barrette digging into her scalp.

He slows down at the entrance to her family home and turns across the oncoming lane, the headlights beaming onto the lawn. The change in speed awakens her. She reaches across the dashboard to switch the car lights off. Blackness swallows them.

“Whoa,” he says, braking.

“Let’s not wake up Mama and Daddy,” Katherine says. His eyes adjust and the full moon bounces helpfully off the two white brick sentinel posts, drawing him through the gate and down the winding gravel driveway. Wetherbye Plantation is not as grand as most of the other antebellum mansions in this part of Mississippi; it had originally, for instance, only supported a handful of slaves. “Servants,” the family called them. A holly hedge has long since replaced the “servants” quarters. The slave burial grounds are overgrown with kudzu.

Jack cuts the engine and the car continues rolling silently past the towering oak tree on the right, the pecan on the left. Long, low tentacles of Spanish moss brush the hood. The mansion looms into view like a Hollywood set piece. Eventually, the Chevrolet glides to a standstill dead even with the front steps. Two glaring sconces light the house’s main entrance, a gratuitous expanse of columns surrounding an open porch.

“Let’s go around the back,” Katherine suggests.

They get out of the car and gently shut the doors so as not to make a sound. She takes off her pumps and tosses them, rather recklessly, up onto the porch where they land sprawled apart. Jack grips Katherine’s wrist with one hand and draws her waist to him with the other.

“Come with me!” She pulls him beyond the boxwoods toward the rear of the house. His shoes crunch on the gravel, drawing an alarmed look from her. He slows like he’s walking through a minefield. She darts across the gravel, every pebble stinging her stocking feet until she reaches the grass. It feels cool and damp beneath her toes; spring has reached the air but not the earth. Jack catches up with her and they take off running past the living room windows, hands locked together. Then they stoop, still hand in hand, creeping under the windows of her parents’ bedroom. They only straighten up beyond the dining room window, bending low again by the kitchen where a single burning bulb on the stove might expose them. They cannot stop laughing.

Finally, they reach the pool patio. The back of the house is deserted. The moon jiggles in the pool water and the pump hums indifferently. The patio smells of chlorine and moss. Back in October, Big James folded and neatly stacked the lounge chairs and nobody has asked him to set them out yet for summer.

“We could be the only people alive in the whole world,” Katherine says, her voice full of wonder. Jack smiles at this—a tad condescendingly, she thinks. Perhaps it was a childish thing to say.

Jack kneels down and skims his fingers over the pool’s surface. The water is icy. A tight mist is beginning to rise from the lawn.

Katherine makes her way to the bank of French doors that line the plantation house’s former ballroom and reaches for a doorknob. It turns in her hand, but she lets it go. Jack stands to admire her.

“You are beautiful,” he says, as if he had doubted it before.

Her curls tickle her bare shoulders, and she senses that her dress must be glowing white in the moonlight. Just as it should be. She wants to call out: I am a goddess to be worshipped. Bring me your sacrifices. But she’s wary of his look, the one that makes her feel so much younger. She reaches down underneath her petticoat to unsnap her garter, and rolls the stocking to her ankles and then off her foot.

“What are you doing?” Jack asks.

“I’m wet,” she answers as she pulls the other stocking off, letting it fall to the ground. Then, although they are dry, she slips off her elbow-high satin gloves and lets them fall to the ground as well. She gives a little frisson as the air meets the pale skin on her arms for the first time in hours.

“Are you cold?” He slips off his jacket and holds it out behind her. She slides her shoulders under it. He yanks the corner of his bowtie until the knot falls apart. If he kisses her now, her lipstick will smear onto him. She rubs the back of her hand over her lips, bright red smudging her knuckles like a freshly bleeding cut. They find themselves laughing again, giddy, still a little drunk. He presses his lips on hers until her mouth falls open and she is backed up against the siding. After a moment, he releases her, coming up for air. He is poised to make the next move, but something holds him back. An unanswered question. She rests her hands on his shoulders and lifts herself on tippy toes, tilting her head back with abandon, her neck begging to be kissed. He obliges, his hand on her bare skin underneath the folds of her petticoat.

Without warning, there is a burst of sound beside them, low, close by their ankles. The distinctive crack of glass shattering. They jump apart. Katherine sees it first, a jagged hole in the lowest pane of the French door, irregular, misshapen, the size of a child’s fist.

“What the . . .”

‘What the hell was that?” Jack asks, annoyed, finishing Katherine’s query because he is privileged to curse without judgment. No such license is granted to debutantes. He catches sight of the damage to the windowpane. “Almighty . . .”

“Ssshhh,” Katherine says, reaching for him, but finding him already gone. He’s poolside again, looking out to the stand of pecan trees in the distant backyard, the last row of civilization before the ground falls sharply to a creek and then up again to weedy hills on the other side. Nothing, no movement, no trace of any creature, just a fluttery and soundless breeze. He turns back to Katherine.

“What the hell?” he says again, less petulantly. “There’s no one there.”

Katherine opens the French door slowly, its base skating the broken glass. No rock, no stick, no object of any kind is visible, only shards of window glass spread into a pattern that looks remarkably like an S.

“I can’t go inside here,” she tells Jack, who is still across the patio. She curls up her toes and shivers. She’s colder than she has the right to be on such a warm April night. Jack comes to her, unbuttoning the collar of his shirt. He reaches around her for the flask of bourbon in his jacket breast pocket. He offers her a drink before he too takes a long gulp.

“Something must’ve blown into it,” he says. “An acorn or something.”

She points inside. “Doesn’t that look like a letter to you?”

“It’s just a coincidence.” But even he, seeing that she is frightened, her mood changed, and believing it his duty to reassure her, doesn’t sound convinced. “We need to get you inside,” he says, using the royal “we” in that paternal way of southern aristocrats, even twenty-three year olds, when talking to anyone not like themselves.

“I’ll get my shoes,” she says, taking off in another run, his jacket flying off her. He picks it up and follows her, more judiciously, catching up only because she waits for him. They reverse their pattern of dips and dashes to reach the front entrance, shaken.

Her shoes are no longer where she had tossed them.

“I’ll find them tomorrow,” she says, her shoulders lifting in a gesture somewhere between a shrug and a shiver.

They take turns downing more bourbon, the last the flask has to offer.

He bends to kiss her, this time with the decided air of a civil good night, a genteel ending rather than the start of something more animal.

“Do you love me?” she asks because some unwritten script tells her to. The answer is of little interest to her.

“Of course I do,” Jack answers gallantly, and they laugh again for the first time since the glass shattered.

‘Well, you know how I feel about you,” she says, suddenly feeling wicked. Something about the glass breaking has slashed open her heart to an unwelcome scrutiny of her exact feelings, and it has come to her that what she feels is want more than love. The desire to feel his skin on hers, to give herself over to his male physicality, is stronger than any sentimental attachment. She reaches up to remove her silver barrette and shakes her curls loose. The barrette pin pierces her palm.

“You know how I feel about you,” she repeats. She suspects, and hopes, he doesn’t really. He’s so sure of himself. She, on the other hand, is veering off script, and dancing on a knife-edge between pleasure and panic.

“When will I see you again?” he asks over his shoulder as he makes his way toward his Bel Air. “When will you answer my question?”

“Come tomorrow,” she says in a stage whisper. “Come tomorrow for Sunday dinner. I’ll let Daddy know, and I’ll get Tam to make extra biscuits.”

The last thing he says before he gets back into his car is cryptic: “Be careful.” Maybe he does understand the stirrings the broken window aroused in her. Maybe he is warning her about something in his own nature that is equally uncontainable. Or maybe there isn’t a hidden meaning in his advice. It doesn’t matter to her. Nothing matters now except that his hands reached a place that no one else is allowed to touch.

“I’ve already been too careful,” she says, twirling to face the door so that her skirt swings out as though she’s dancing the twist.

In her bedroom, she strips off her debutante costume: the ridiculous layers of white satin and tulle, the crinoline tutu petticoat, a slimmer nylon slip in a color between pink and tan the catalogue calls “flesh,” and, lastly, the pointy brassiere that lifts and confines her breasts into dual pyramids. Now, almost naked, when she unsnaps the bands of her garter, Katherine remembers her hose and gloves. Still lying in a puddle on the side porch.

She pulls on a set of pajamas, then tells herself if Jack saw these he really would think I am just a little girl. She places all her battle-wear on hangers which she hooks over her closet door for March to launder and iron.

The former ballroom of the plantation house now serves as a recreation room, a brand new television set at one end, a pool table at the other, various plaid couches and leather armchairs stationed in between. Katherine doesn’t dare turn the lights on. She tiptoes in the direction of the French door with the broken window. A low band of clouds obscures the moonlight, but she feels and smells outside air making its way into the room. The tyranny of the shattered glass stops her from crossing the threshold to retrieve her gloves and stockings.

Katherine doesn’t even know where the broom is kept. She guesses in the kitchen utility closet. Opening it for the first time in her life feels like an act of stealth. Indeed, waiting for her, like backstage props, are a straw hand-brush and tin dustpan.

As she sweeps up the glass, she notices an inky dark liquid seeping onto the dustpan. The more she sweeps, the more the liquid oozes up the brush bristles. Is it raining in? The pool’s surface is as smooth as a mirror. The patio itself is dry. She dips her fingertips into the liquid. It feels warm, slick, and smells faintly sweet. Wisps of clouds cross the sky, fast moving now. The moon reappears. She holds her hand nearer the window just as the moonlight intensifies. The liquid appears maroon, then crimson, and finally, scarlet.

She finishes sweeping up the glass and scurries back to the kitchen to discard it. The light above the oven confirms the unmistakable color dripping from the dustpan. Dark blood covers her fingers, soaks the tea towel she has grabbed, and snakes toward her elbow. She quickly throws the glass and the tea towel away and hides the broom and dustpan far in the recesses of the closet. She runs water over her skin until the blood has washed completely away, leaving the porcelain sink deceptively white.

Katherine races back breathlessly to the French door, flings it open and hunches down to retrieve her gloves and stockings. She doesn’t notice that the deep stain on the floor has disappeared. She’s too stunned by what she sees outside. Laid neatly together, heels and toes aligned, are her shoes, the pink satin pumps she carelessly tossed aside earlier.

It’s almost five before Katherine gets in bed, both exhausted and exhilarated. She has no hope of getting more sleep. Once, she hears footsteps creak on the stairs, and for a moment she has an indecent hope that Jack is sneaking up to her as filled with wayward thoughts as she is. Her room, even with twelve-foot ceilings, feels sultry. March opened the windows and closed the louvered shutters at dusk, but the breeze has not penetrated the bed curtains. She kneels on the satin quilt and slides the side velvet drapes to one corner of the bedposts. Instantly, a pleasant coolness wafts over her, smelling delicately of lilac blossoms. The room is a pre-dawn grey.

Katherine moves to the foot of the bed and yanks that cloth open. She gasps. There, unmoving but wide-eyed, stands a girl, probably not more than ten years old. She’s dressed in a rough burlap dress a shade of brown lighter than her skin. She backs up from Katherine timidly. She must be a child of Tam’s. Katherine doesn’t even know how many children Tam has.

The girl must have merely wandered into the house, curious. With this thought, the presence of the girl seems neither frightening nor strange to Katherine. Instead, she wants more than anything to touch her. The girl retreats from Katherine’s outstretched hand, her skinny legs quivering.

“What are you doing in my room?” Katherine asks with a natural authority. She scrambles out of bed. It occurs to Katherine that the child has not guilelessly wandered into the room. She is the one who broke the windowpane, stole and then returned Katherine’s shoes. Her name undoubtedly begins with an S. Katherine is at once angry and disconcerted. The girl is cornered, and Katherine clutches her arm, intending to pull her from the wall with a vulgar violence. The girl’s terrified eyes meet hers. She appears unable to speak, her mouth gaping, her throat caught, and a wave of pity sweeps over Katherine.

Katherine runs her fingers along the hem of the girl’s dress. It’s expertly hand sewn in evenly spaced stitches. She is very real, this child, even without a voice. The girl wriggles out of Katherine’s grasp.

The young girl begins to shake uncontrollably, and as more light enters the room from the rising sun, Katherine sees that there are tears streaking down her face. Katherine raises her palm to wipe them off but the girl cringes. “I’ll take you home,” she says firmly, rising to fetch her robe, although she has no idea where the girl might live. She’s not even sure where Tam lives. When she turns back to the corner, the child is gone. Katherine quickly reaches the door, but it’s still bolted. She lets out a small scream, covering her mouth with her palm.

She was dreaming, of course, she thinks, climbing back into bed. It has all been a dream, the broken glass, the blood, and the girl. Perhaps even Jack is a figment of her imagination. Perhaps it would be better if he were.

She sleeps hard after that, in a bright room, the curtains of her bed open. The sound of March closing the window sash wakes her up.

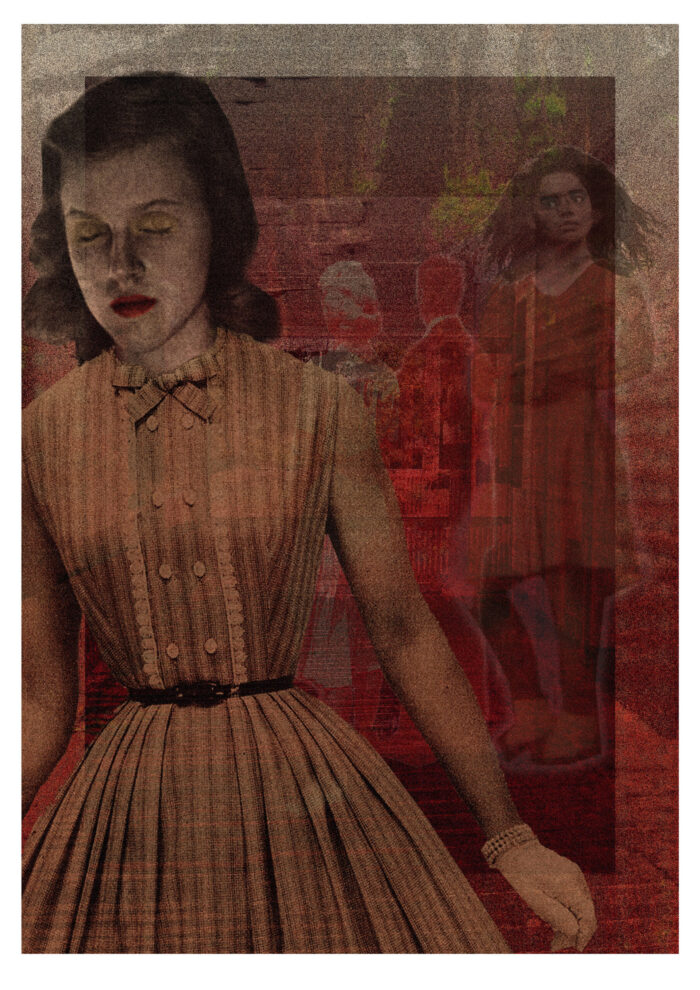

“It’s Palm Sunday, Miss Katherine,” March says. “Your mama will never forgive me if you’re not ready on time.” She leaves the room as soon as Katherine jumps out of bed, closing the door to the upstairs hallway quietly. She has laid Katherine’s peach Sunday dress out on the velvet chaise lounge, the skirt neatly fanned out, perfectly pressed. A double-wrapped tan belt constricts the waist. Tan pumps sit on the floor. White will have to wait until Easter. Katherine hurries to armor herself in a brassiere and slip and then buttons her dress over them.

One look in the mirror tells Katherine it was a mistake not to put curlers in her hair overnight. Her hair looks wild. She brushes the curls out, punishing her hair, and wraps it into a quick chignon. Then, she pins on the peach felt cap that matches her dress. How artificial she looks compared to last night’s visitor.

Sitting at her vanity, she paints a bright orange lipstick on with a tiny lip brush. The lipstick lays cakey and dry on her lips. Her mother calls up to her from the base of the curling staircase. She has missed breakfast. It’s time to go to church.

Her parents have already gone to the car by the time she emerges from her room. She bounds down the stairs, carrying gloves and a tan leather pocketbook in her right hand and gripping the banister with her left. The wood feels slightly damp. But it isn’t until she goes to put on her gloves outside that she notices her left palm is covered in blood. Again. Like some damn Lady Macbeth. Big James holds the rear door of her father’s Cadillac open for her. She clenches her fist and climbs in. The blood wipes off her left palm with her cotton handkerchief easily enough.

On the car ride home, she takes off her gloves. Her hand looks clean.

“Daddy,” she begins, “I asked Jack to dinner today.” She picks up her palm frond cross with a bare hand and the pin pricks her thumb. Her mother turns to her. “If that’s all right with you, Mama,” she says, smiling. Behaving like she’s expected to.

“Oh, I’m so glad,” her mother says.

Don’t add, “He’s such a nice boy,” Katherine thinks. I don’t want him to be a nice boy, and I’m pretty sure he isn’t one.

“If you want my opinion, young lady,” her father interjects from what seems to Katherine like a great hollow distance, “You couldn’t do better. I’m very proud of you.” Then after a careful pause, he adds, “You’re a good girl, Katherine.”

“Oh, thank you, Daddy,” Katherine says sweetly, but the words sound to her like someone else has spoken them.

When they get home, the first thing she does is make her way to the ballroom. Big James is there on his knees, placing a pane of glass in the French door, filling the gap.

The banister is dry. The stain on her handkerchief has turned the color of milk chocolate.

Jack arrives right on time, a few minutes after noon, to find Katherine sitting on the light green settee in the formal living room, her gloves on her lap, and her pocketbook beside her. There’s no room for him to sit next to her, so he kneels on one knee and takes her hand.

“Did you get any sleep last night?” Jack asks, his thumb rubbing her fingers, stirring something deeper in Katherine.

“Did you?” she asks in return. Her mother is just now descending the staircase, coming upon a scene she is bound to misunderstand. She makes a quick apology and retreats through the dining room to the kitchen. Katherine has forgotten to tell Tam to set an extra place.

“Not a wink,” Jack laughs. “I couldn’t stop thinking about you. When will you answer my question?”

“Oh, Jack, let’s go into town tonight. I want to hear music, good music, not that boring stuff they play at cotillion. Take me out, will you?”

Someone is on the porch. Katherine has only barely seen a shadow move by the window. It can’t be Big James; he’s either in the ballroom or changing into his white jacket and gloves to serve at table. She jumps up to look out. Jack rises and puts his arm around her shoulder. With his other hand, he plays with the pearl button at her breastbone.

“You can’t put me off forever, you know,” he says lightly, his breath hot on her neck, his fingers on her collar bone.

Katherine doesn’t turn to face him. She’s too busy watching the man on the porch, and how oddly he’s dressed, in rough cloth, brown and dirty, his feet shoeless and cracked. She starts to remark on this to Jack, whose eyes have followed hers. But she stops herself: Don’t say everything that pops into your head or he’ll think you’re crazy. Maybe she is. The man outside approaches the window, his eyes blank. He’s too bold, this man, to come right up to the window like that. But the window frame itself begins to break up, deep cracks expand across the plaster wall before her eyes. She turns away, afraid. Still, Jack says nothing. When Katherine turns to look outside again, the porch is empty, and the wall looks normal.

Behind Jack and Katherine, her father gives a small cough. Jack hurries to shake his hand. In the dining room, March is setting an extra place.

“Thank you, March, that’s mighty kind of you,” Jack says jovially.

“It’s nice to see you, Mr. Jack,” March answers. Her real name is Marcia, but the family has called her March since Katherine’s brother coined the name as a toddler. Katherine doesn’t even know Tam’s real name.

Big James carves the Sunday roast, places each person’s plate on the tablecloth in front of them, and stands with his back against the wall.

“Did you get the window fixed?” Katherine’s father asks him.

“Yes, sir, good as new.”

Katherine and Jack exchange a glance that she is sure her mother has noticed. They bend their heads as her father recites the blessing. On her china plate, blood seeps from the sliced beef to the flowered edge, turning the rice an unappetizing pink. Under the table, Jack reaches for her hand. She lets him hold it, briefly. Her mother smiles.

That evening, Jack drives her to a club in town. They dance energetically, and after the first few songs, Katherine confesses she’s tired. He leads her to their table near the dance floor and orders two more bourbon and cokes. As they sit down, a girl who looks like she’s a year or two younger than Katherine approaches their table. Her presence is startling. She should be back on her own side of town. She doesn’t belong on theirs.

The girl stands over them, unable to speak for herself. Jack doesn’t look at her at all. Katherine shivers, thinking, this girl is like the others, a figment of my imagination. She reaches out and grasps the girl’s arm tightly, and is on the verge of telling her to get out of there when she thinks better of it. She could be talking to thin air. The girl looks at her in pity before returning her gaze to Jack, her eyes filled with reproach. Jack still doesn’t look up. Katherine excuses herself and heads to the powder room, glancing back several times to see if Jack has spoken to, or even acknowledged the other girl. He never does. The girl is gone when Katherine gets back to the table. She asks as dispassionately as she can, “Who was that girl?”

“What girl?”

“I thought that girl over there looked like she knew you,” she says, tilting her head to the sole female in the room sitting alone, even if only temporarily.

“Never,” Jack says. He leans in and kisses her. She feels the familiar rush of blood through her veins whenever his skin meets hers.

“I want to get out of here,” she tells him.

He stands and lifts his jacket from the back of his chair. “I’ll take you home.”

“No,” Katherine says firmly. “Take me where you’ve taken the others. . . .” Like that girl, she doesn’t say out loud. “You must have somewhere you go.”

“I don’t know what you mean.” His face has turned pink.

“It’s okay, I don’t mind. Just take me there now.”

His expression takes on a shocked look she believes is feigned. He’s pleased, in spite of what is expected of him by everyone but Katherine.

“I couldn’t,” he says, a little too slyly. “Not unless you answer my question, that is.”

“This is my answer,” she says.

“Is it yes, then?” he presses.

She can’t lie outright, so she nods her head, a physical not verbal lie.

“The hunting cabin,” he says. His family owns a cabin on the riverside between Natchez and Vicksburg, about a half hour away, but she has never been there. So that’s where he took the girl who stood at their table. What happened to her? “Are you sure?” he asks, like a little boy who has just been offered chocolate.

“What do you think I am?” she asks in that same voice that has become foreign to her, but that speaks the words Jack expects to hear.

“Your parents . . . it’s already late. . . .”

“They won’t care, once we tell them our news,” she says, beginning to fear that the stranger who speaks for her will have her way in the end, and that she, the real Katherine, will fade away inside the girl she was not that long ago, obedient and blind.

“I love you,” he says, and she feels compelled to say it back to him.

Neither of them speaks the entire drive north. It has grown pitch black, the hills and the woods rushing past them. At the cabin, he reaches into his pocket and pulls out a tiny box. He takes her hand and slides the diamond ring on it. Good girls don’t fuck without a ring.

Afterwards, while he showers her blood off, and she lies on a towel, the girl from the club appears at the foot of the iron bed. Katherine sits up. “Why are you here?” But the girl cannot speak. Her belly is slightly swollen; blood covers her dress and runs down her legs. “I think I know what happened to you.” The room is empty again.

Jack, stepping out of the shower with a towel wrapped around his waist, begins to fade away, literally to disappear, as if he is the apparition. The walls of the cabin turn blood-red before they, too, melt away and leave Katherine staring at a universe of stars, nothing holding her down except the sound of her own breathing. She squeezes her eyes shut and intently listens for the noises Jack makes as he enters the room, the rustle of his clothes as he gets dressed, and his footsteps on the wood floor. “We need to get you home,” his voice says.

He holds her tight and long at the front steps to Wetherbye Plantation. He didn’t turn the car lights out or cut the engine in the driveway tonight.

“I don’t want to spend another minute without you in my arms,” he declares, lifting her hand and twiddling with the ring. He had held the ring out to her when he asked her to marry him last Friday, his first night home on Easter break from Ole Miss. But she hadn’t put it on then. She had put him off cleverly, he thought. He didn’t bring it up again until the early morning hours after the Natchez cotillion, after the French door window was broken. And even then, he was lighthearted about it. He came to Sunday dinner in full expectation of an affirmative answer. But she was acting strangely, staring out the window as if seeing something he could not, as if she had knowledge that he did not. It was only then that he began to doubt her. Her behavior at the club scared him. How could she know about the others? How did she know about the girl standing at their table? The girl had a name. Sometimes he whispered it to himself alone in the dark. Angela. She had appeared to him before, seeming so real, so flesh and blood. But she couldn’t have been.

That fucking abortionist. He killed her, not me, he thought. He had willed his eyes to unsee her and tucked his shame neatly away where he hoped it couldn’t hurt him.

But Katherine, somehow, knew. Katherine. Katherine would be his redemption. If he could just rein her in. Sitting at the club table, watching the couples dance, he sensed that she was slipping away from him. And with her the surety of the future he had mapped out for himself, a continuation of his parents’ lives, even of his grandparents’ lives. The winds of change be damned. When she suggested he take her to the cabin, he agreed in order to gain possession of her. It was done. She was his.

At her doorstep, he releases his grip on her reluctantly, and says, tenderly, “You are mine forever.”

She laughs, just like she did on the dark patio after the dance. Only this time, she hears her own laughter from some far away place, a place Jack can’t go. “We both need sleep,” she says and climbs the steps to the porch. He bows deeply, a gesture that two days ago she would have found charming.

As she mounts the curve of the interior staircase, she catches sight of a pile of clothes by her bedroom door. It’s too dark to make them out exactly, but even so, she thinks they look like the clothes worn by the little girl she saw in her room. As she approaches her door, she sees that it’s the little girl’s body itself, face down on the wood, her arms and legs the only flesh visible. Her skin is deep grey, the color of death. Katherine rushes to her, feeling a powerful and unexpected grief. She scoops her into her arms and cradles her. If only she can warm her up. Her face is bruised, her bones cracked, broken, and her lips swollen and cut. Her hair is matted with dried, dark, old blood. The floorboards below her are soaked with her blood. Katherine’s dress is already saturated, but she doesn’t care.

“Who did this to you?” Katherine cries, not caring if she wakes her parents. She begins to weep, understanding now that this precious child was beaten to death here on the plantation, just like she understood what happened to the other girl from the cabin. Katherine holds the little girl, gently rocking to and fro, until she finally falls asleep herself. When she wakes, late the next morning, her arms are empty. The girl’s body is gone. But the blood on the floor is wet, the stain still growing. Katherine pulls herself up, and turns away from her own room. She slips the ring off her finger and drops it onto the pool of blood.

As she descends the stairs, she sees her parents in the pea green living room, her dad in the biggest armchair, her mother in a small velvet slipper chair beside him. Blood runs down the walls around them. They themselves start to vanish, bone and flesh disintegrating before Katherine’s eyes. In the front hall stands a young man, more real than Jack can ever be. He stands firm, not beckoning, not welcoming, simply being. Blood trickles down the wooden posts and pools along the floor. The walls around him collapse. The ceiling fades from white to red to gone. There is no longer an upstairs, only sky.

Katherine knows what she wants now. Both what she wants to do, and where she wants to do it: anything else, anywhere else.

She walks past the young man and out the front door into the sunlight. A family, beautifully corporeal, has gathered on the porch. A woman, holding the hand of a young child, a white-haired grandfather, a husband, and a teenage daughter. Their eyes follow Katherine as she emerges from the decomposing house. They do not need to be seen by her to exist. For her part, she can no longer unsee them. Behind her, the house becomes ever more immaterial. Katherine looks at the long, winding driveway, the low hanging Spanish moss, the ancient trees that line it, and views it for the first time as an exit, not an entrance. It’s possible to leave. It’s imperative to leave. Behind her the mansion falls to the ground under the weight of understanding. The people next to her have disappeared. She alone has the privilege of departure. They cannot follow her to freedom.

Treanor Wooten Baring is a freelance writer, playwright and poet living in Houston, Texas. She grew up in rural Mississippi and then south Florida. She began her career in the Arts as a producer-director for Mississippi Educational Television, and has continued to write for both the young and the young at heart. Her middle school plays have been performed in the U.S., Canada, Australia, the U.K. and Vietnam. She will insist, to anyone who will listen, that Jane Austen is not about teacups. And that ghost stories tell us as much about the living as about the departed. Although she has always enjoyed reading them, “The Unseen” is her first ghost story.

Treanor Wooten Baring is a freelance writer, playwright and poet living in Houston, Texas. She grew up in rural Mississippi and then south Florida. She began her career in the Arts as a producer-director for Mississippi Educational Television, and has continued to write for both the young and the young at heart. Her middle school plays have been performed in the U.S., Canada, Australia, the U.K. and Vietnam. She will insist, to anyone who will listen, that Jane Austen is not about teacups. And that ghost stories tell us as much about the living as about the departed. Although she has always enjoyed reading them, “The Unseen” is her first ghost story.