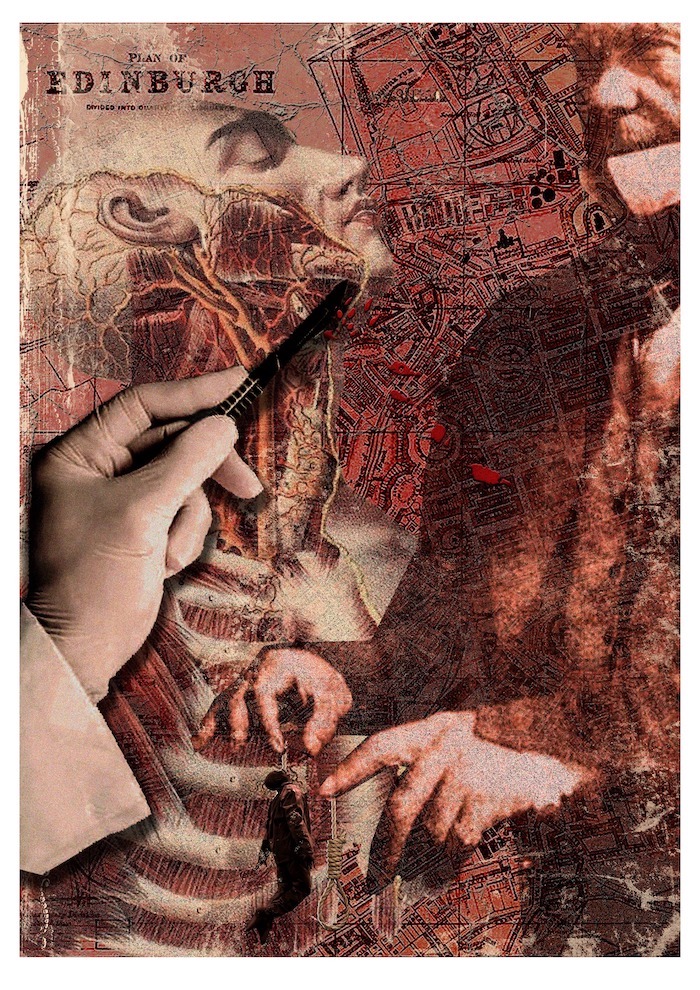

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

WINNER, FALL 2021

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY ROBIN RIOPELLE

I’ll be as honest as I can, which is rich, given the circumstances, but here it is: the very worst thing about this place is the lack of booze. Everything else is shite, of course, but that, that’s a feckin’ tragedy on a whole different order. I’ve been buggered by a village priest, felled by the miasmas of Tanner’s Close, subjected to the ravings of Hare’s harridan on my character and general demesne—but this?

Better to be nameless than drinkless. Ah, but it’ll be the name William Burke they’ll remember, and that’s an eternity of a different, better sort. What will Hare’s terrifying virago, Maggie, get? Forgotten within a year, mark me. And me own sweet Nell—well, her name’s already drifted away, floss on the wind. Hare himself? A little longer, perhaps, useless fucking gusset skid. A little longer for the masses to gowp, to gossip.

But nowt as long as me. I’d drink to that, if there was drink to be had.

Davy Ferguson thinks Knox is a vulture, a creepy Lowland vulture, and the night welcomes such as him. Too cheap for nowt but twa’penny candles and Knox had not lit one ‘til Davy pointed out that they needed to see the money to count the money. Seven pounds and cheap at twice the price, in Davy’s limited opinion. There was the matter of the condition of the corpse. Surely it ought to be intact, given there was money involved. Though what cares Knox if there’s five fingers and toes, a head? What matters that to the slavering students?

So be it, Davy Ferguson thinks this night, like he has for all the others. He also thinks the price will be going up, and soon. Supply and demand. They are well-versed in economics, here in Edinburgh, almost as much as in the medical arts.

What had he supposed, Davy, coming here to study the bloody business? That Edinburgh would be better than Glesgie? Summers was always too short, the Gorbels tenements too ripe. He did not want his father’s job, did not want to wrest rent coin from the destitute. His mother had said go, and backed it up with the money she’d gotten from Aunt Nan, bless her soul. His father, name second on the door in gilt letters, separated from fame and fortune by an ampersand and alphabetical convention, had not looked up from his housing factor’s desk, mind always on the leger and the bottle in the drawer.

Not the first of his family to study, but the first to leave the grey city. Medicine, not economics. Wasn’t science grand?

So now, having met these lads, voices corrupt with the broad and the sharp of Ulster, Davy having passed through the lodging house kept by one of their wives (they called them wives, but Davy would be boiled in oil if they’d ever heard the banns or whatever it was that Catholics did to marry), and come out the other side to the university lodgings, now Davy was their acquaintance, their middle man, their go-to in a sordid exchange.

They caged bodies in this city’s graveyard. A balance between piety and commerce, always.

Davy: a mutton-fat candle stinking in his hand, at the service entrance of Knox’s premises along Surgeon’s Square. Knox: safe in the operating theatre, awaiting next morning’s dissection. The Irish lads: reeking of whisky, silly, grasping.

This night, the dead woman, to Davy’s dismay, looked exactly like his Aunt Nan. She might have been the twelfth, or the thirteenth, he’d tell the courts later. She looked peaceful, almost, except for the bloody spittle on her blue lips. Might have died in her sleep. Might have, but hadn’t.

The first fella, he’d given us no trouble. Other than being deceased, I mean. Hare’d been in a state, whipped up by Maggie’s caterwauling. Oh, what to do, what to do. He’d come to me, a’ course. I’d kept an eye on his ugly mug, lean and hard like a piece of dried meat, a dog beaten once too often, bite you as soon as look at you. Oor kind useful enough for the army on the Continent, dying when required, needed for the dirty dangerous work of canal-digging when the fighting was over. We’d bonded, you could say. Two Irish souls what found each other in the shitty narrow Edinburgh wynds.

Then Maggie with her lodging house. She’d had her hooks in Hare, married him right quick after the first mister croaked. My Nell hadn’t liked her one bit, but that’s women for you. Sized each other up and found each wanting in some critical aspect that was akin to a state secret.

Maggie was all business when she wasn’t haranguing us. This Donald, well, he’d died abed, owing. All swoll up, weighed a fair tonne, so he did. Not good for business, Maggie had whispered, a banshee on the wind. Not good for business, my arse. November, the new students in, famous as fuck, that school. A need for education, and the materials to do it proper. A body owing, debt not erased by death. I could sell the clothes, Maggie had muttered.

No ambition, that woman.

We can do better n’ that, Hare suggested, recalling aloud the beginning of the autumn, and the students, all scrubbed, ready to start, ready to learn. It was a fucking match made in heaven right from the jump.

We’d ordered a coffin, filled it and sealed it with the coffin maker right there. Then un-everything’d it back at the house, stuffed Donald under his own bed. Filled the box with tanner’s bark, he’d weighed a horse, had Donald. Buried that.

As fer Donald, well, he paid his debt. We were given seven pounds, two months wages, at least. Considering what the students paid, it seemed fair. Donald was a windfall, you see. A lucky break, pennies from heaven. The wee lad who’d answered the door to our knock, he’d given us pause, though. We’d be glad to see you again, he’d said. Blame him if you need someone to blame.

They’d come back in the new year, long after all the coal and bread of Hogmanay. They told Davy the man had died of fever, no kin. The man, a miller by trade and Joseph by name, Davy now knew (everyone knew), had no kin indeed. Joseph had told the missus of the lodging house, so he had, said Burke, the bigger one, the smarter one, all smiles and dark dancing eyes, smell of whisky a perfume, a calling card, like Davy’s father at his factor’s desk.

It could have been fever, Davy supposed. Knox had said fair game, and Davy had given over, ten pounds this time.

The fever’d spread, Maggie had said, that thin, viperous voice, fishwife sharp. You’d be doing us all a favour. And the kind of fever that fills the lungs with fluid, that you notice when the lips turn blue. Could be fever. Could be a big man sitting on your chest while a lighter man pushed a pillow over your face. Either, depending on your point of view.

Thing is, Knox didn’t care, and we didn’t care. Not with Joseph, who was practically dying anyway. As was that peddler from Cheshire. A contagious pair, them. The whole neighbourhood could have been away with the murderous vapours from either of those two poxy pricks. We were doing our civic duty.

But the Hares’ lodging house was no place to fall sick, if you ask me.

The salt seller arrived in a tea trunk, and it was impossible, even for Knox, Davy supposed, to pretend that she had conveniently fallen ill with no kin to claim her. Knox was a doctor, as though that mattered, when even a fresh-minted student like Davy could tell. As soon as the lid was off in the narrow corridor leading from the back door to the surgical theatre, Davy smelt cheap whisky and street filth. Oh, well done, Knox hovered at his elbow, his one seeing eye alight (how you could properly dissect a body only having one working eye was a mystery to Davy; Knox said he’d been blinded at Waterloo, but the scuttlebutt said childhood smallpox). So fresh. Well done, lads.

They were not lads, not any of them, Davy decided then and there.

Knowing what people want is half the battle, you see, and in this neighbourhood not so much a battle as a scrap of trouble soon overcome by the barest of wits. Because all anyone wants is oblivion. Something to wipe away the torment of lost babies, or an unforgiving landlord, or a living made redundant through mill and cattle and clearance.

We gave them that, the oblivion. It was the least we could do. Oh, I discovered a vocation for that part, the glug of gold poured into their mug, the fire in the hearth of Hare’s front room steaming us a’through that winter. Too icy to go home, if they lived elsewhere. Just another b’fore bed, if they were destined for the rooms upstairs.

There was that time at my place, the place I shared with Nell. Two ladies, Mary and Janet, found at Canongate, so my digs was closer. I’ll tell you straight: I fancied Janet, and her friend was already staggering. Oh Bill, Janet the looker said, not staggering, sure, but not far off, Oh Bill. I thought with enough whisky the one would go down while I chatted up the other. Happy, they was.

I hadn’t precisely forgotten about Nell. I’d just not remembered her. It can happen, dark cold night, courage in the glass, a lovely thing like Janet with her big eyes and her not-awful teeth hid behind lips that lifted often, like bare toes poking out from beneath a too-short skirt. What was I to do?

Nell arrived home raving, and I suppose, in hindsight, I’d perhaps deserved it. A glass from my hand across the room to her brow barely dented her beratements, I’m sorry to say (I did love her, once, Nell). Janet cried how was I to know he’s a wife and scampered. Nell soon after, but back quick with the Hares. No flies on Nell. Nevertheless, we locked our ladies out the room and did our evil to that slumped mess, Mary Paterson. I had a tea chest at the handy, once emptied of moth-chewed blankets. The women pounded at the door, the racket covering any noise Mary’s boots rattling against the floorboards may have made.

By my estimation, it’s the only time the missuses agreed on anything.

Knox marvelled that the body was still warm. He packed her in whisky for three months before dissecting her, standing room only.

Oh, I confess, they all start to bleed into the other, if you’ll pardon the expression. The auld woman, and her daughter what followed, looking for her. Effie, who’d once helped me collect leather scraps for my cobbling. That young lass too drunk to stand. A passing constable actually helped get her to Hare’s door. We had a laugh about that, after.

But as long as someone was cleaning vermin from the streets, what did they care? The students were taught, the coppers made their rounds, the tavern sold their whisky. Maggie flogged their clothes, and kept the skirts of some. We’d fight between us, especially if there were clothes or money or drink to be divided. Maggie was right tight-fisted when it came to any of it.

The only time Davy saw anything other than feckless charm on the face of the bluff one—the other was always a scything shark, restless and blank-eyed—was the time they brought the herring barrel instead of the tea chest. They’d needed bigger, Hare explained. Burke grunted, jiggling it onto the cracked tile flooring immediately inside the Surgeon’s Square door. Knox had sprung for a lantern now, for Davy to better to inspect the goods.

Open it, Knox muttered, and Burke, the big ‘un, the once most likely to share the craic, hesitated. You can keep the barrel, he said, as though he was throwing in something for free. Nevertheless, it was opened, and Davy turned away.

A grandma and a wee boy, both blue on the lips, the boy curled like an eel into the curve of his granny’s embrace. Burke’s face was still, pale in the gleaming lamplight. It was past midnight, fully dark, now well into spring. The streets slick with rain, the smell of coal wafted in with the stench of drink.

No, I’ll not talk of it. Enough was said during the trial. But how could we leave him, once his granny was done for?

The horse knew. Refused to pull the cart further than Grassmarket. We’d had to hire a man with a handcart, and that was expensive come midnight, let me tell you. Knox’s boy with the light, trembling, the expression on his face, god damn him.

And then, you know what that maniac Hare did once we’d got back to the lodgings, Maggie and Nell safe in their beds, inventing ways to spend our money in their sleep? You know what that crazed lunatic did? Shot his horse, right there in the stable. He was fair livid. Maybe it was the bairn, but I doubt it. Hare didn’t give a shite about the boy.

Only an Irishman woulda shot his perfectly healthy horse; A Scot would never have done it. Foreigners, we were, marked by the ease we’d put outrage before profit.

Everybody knew Daft Jamie. Davy always reckoned that’d been a mistake on their part. Crooked legs, that slack mouth, laugh like a crow on a stump. The students passed him if they ventured down into Haymarket, looking for action. Daft Jamie, crying out for pennies, would dance a wee jig if you called for it. Nowt about the gormless bugger was harmful, Davy thought.

They all knew the lad, that was the problem. Edinburgh wasn’t as big as all that.

Knox was sure-handed, flinty. Though he’d more cadavers pickled in barrels, Daft Jamie moved to the head of the surgeon’s line. Without any of his assistants there, Knox—the squint-eyed prick—took off Jamie’s head and feet, presented him like a gutted pale fish in the theatre so all the kids saying Wist, awae wi’ ya, Daft Jamie’s nowt been seen fer days now here’s this, would quiet their voices.

I don’t know why you’d say luck of the Irish, because there’s fuck all lucky about us. Witches night and all, and damned if the woman wasn’t a Docherty. Maybe there’s some on me ma’s side of the family, and maybe there’s not, but that’s what that auld woman thought because that’s what I told her.

Hare and I finished her the usual way. Trouble started when another lodger looked in the room, maybe to find her missing stockings, or maybe to rob us or find us out. Maybe God in all his usual wisdom sent her to put a bow on our sad story. I hardly know. But there she was, Missus Docherty under the bed where no stockings were ever found, and where nobody could say she’d crawled to die.

And then I became famous.

Davy didn’t go to the trial, though he wanted to. Somewhat surprising that it was Burke who’d hang and not Hare. In Davy’s considered and considerable opinion, Hare would give the devil the willies. But the broadsheets said Hare had told the constables everything, and pointed his thin deathly finger at Burke. Who had laughed and raised his brows and made a full confession.

There was the matter of culpability. The two Irishmen had only provided what the market demanded, and didn’t a Scot understand that principle? But Davy knew how it worked, here, where the poor stayed poor or they stayed dead, and the rich sent their sons to school. But Davy would be lying if he said he wasn’t frightened. There was being guilty and then there was guilt.

But Burke, big laughing Burke and his full confession. The wives were blameless, he’d said, and claimed Knox knew not from whence the bodies came.

The authorities said Knox was deficient in principle and heart, and Davy reckoned they were correct on that point, but they didn’t charge him. They didn’t need to. They had a man in their cage, and no-one wanted more questions than could be conveniently answered in a drawing room whisper. The sons in the theatre, knowing. Davy at the door, knowing.

Afterwards, Knox made a fortune on the lecture circuit.

They told me what to say, ‘a course. That was the way of it. Someone had to answer and Hare was the King’s Witness, so that left myself. What good would it have been, throwing Nell and even the awful Maggie to the Scottish wolves? What purpose to killing more Irish on foreign land?

But truth have it, the scaffold called to me. Dearth a’ whisky in the clink, you see.

There in Edinburgh Parliament House to be judged, Christmas Eve, for fucks sake. You’d think they’d all have better things to do. We were judged together, Nell and me. Virago Maggie on the stand with her bairn, hollerin’ to beat the devil. Hare standing, sound of poverty in his vowels and throat clearin’, smirkin’ the whole time: Oh, Burke he’s what did it all. I only helped roll the barrel to the doc.

The little fella with the big eyes and the spots like coughed blood on snow said he’d seen us. That we’d delivered bodies to their stoop. Did not say that every time his hand had shook, easy enough to see when yer holdin’ a feckin’ lamp, light scattering on limewashed walls. Still, he’d recognized Daft Jamie, and he’d seen the granny and bairn, and he’d seen that woman Paterson, the one what couldn’t be fashed to leave wi’ her friend when she shoulda.

I saw it in their eyes. Not thanks, why would I ever expect or want that? Relief. That’s all. They think they’ll get on wi’ their lives, so they do. They think that’s what’s to happen.

Even through the lies, they didn’t have enough to convict Nell. She tried to see me, they say, and I believe it. Now, no one knows her name. Given the choice, I’m sure it’s a preferred state. Maggie whisked herself back to Belfast, and disappeared into the soot and the shipyards. Lives wi’ whatever she calls a conscience.

I wait here. For Hare. For him, I will wait, always.

Thank Christ, Davy thought, hearing his lawyer’s voice, seeing the paper in shaking hand, the letters crabbed and crooked and so wonderful. A miracle.

“Burke declares docter Knox Never incoureged him Nither taught or incoregd him to murder any person Nither any of his asistents. That Worthy Gentleman mr Fergeson was the only man that ever mentioned any thing about the bodies He inquired where we got that young woman Paterson. Signed William Burke prisoner”

It was enough for Davy to go on. It was enough to stay here in Edinburgh, to never go back to Glasgow, to never see his father’s hand made into a fist. It was enough that once all this had blown over, once some other grisly set of murders elsewhere had commanded the attention of the crowd, eager for sordid details, that he could get on with it. The business of being an adult in a world full of blood.

The details are grim and delightful for the righteous, god-fearing lot of yez, so I shall recite them. Because ya know the law o’ the land. Who yer meat belongs to once yer a ward o’ the state. At least it was not that fuckin’ ghoul Knox which done it. Professor Monro, himself, if you so please. I’m a fucking star, I tell ya.

They sold tickets, had to traipse them through the theatre as Monro took me apart. At one point—and I am not making this up, how could I?—Monro calls for a quill and dips it once, twice, three times, to compose a wee note. “This is written with the blood of Wm Burke, who was hanged at Edinburgh. This blood was taken from his head.”

Would it matter, I wonder, if the blood was from my black heart? From my foot? From my right nut?

Ah, now, you wonder, what else? This is not enough for yez, I can clearly see. So. You can visit me, so you can, at the medical school. There’s a book bound with my tanned skin, though for the life of me I can’t bring myself to read it. No, I am not joking. This is what passes for civilization during these times of science and railroad.

And all of this I can take.

What I wait for is sweeter than this, an elixir made from heaven’s apples, so near to me now.

They put Hare in a carriage bound for the Lowlands south of Glasgow, but he was found out and harried into the local constabulary at Dumfries. Disguised as a woman—oh, the sweet sweet elixir so close!—he was put on the road south. To England. And that must be enough for any Irishman, dead or alive, for their turncoat comrade to be put on that road.

Know that he wasn’t happy. Know that Englishmen looked upon his sorry Irish drunkard’s ravings in the middle of Manchester, or London, or Birmingham, that life passed him by and that he’d die unknown, nameless, a corpse not even worthy of a coroner’s slab. That the only person who would whisper his name with any sort of affection would be me, calling him home.

“The [University of Edinburgh Anatomical Museum] holds human remains prepared for teaching anatomy since the 1700s as well as zoology specimens, phrenology busts and masks, sculptures, artworks and models created to teach anatomy in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The museum is also the location of the skeleton of murderer William Burke who, along with his accomplice William Hare, supplied the anatomy lecturer Dr Robert Knox with bodies for dissection at his anatomy school in Surgeon’s Square in the 1820s. On the 1st floor leading up to the museum there are two Asian elephant skeletons and a jawbone collected from a whale stranded on the beach at Longniddry near Edinburgh in 1869.”

___________________________________________________________

Robin Riopelle possesses an impressive roster of ancestors including Ulster Scots and honest-to-God Lowland Scots, as well as a lovely set of Irish in-laws. In her museum work, she’s written quite a bit about the First World War, designed game apps about Cold War spies, and is currently developing exhibitions about vintage tractors and space photography (though not the same exhibition, of course). Deadroads is her debut horror novel from Night Shade Books. She is working on an alt 18th century dark fantasy about elections. She lives in Ottawa, Canada, with her criminologist husband.

Robin Riopelle possesses an impressive roster of ancestors including Ulster Scots and honest-to-God Lowland Scots, as well as a lovely set of Irish in-laws. In her museum work, she’s written quite a bit about the First World War, designed game apps about Cold War spies, and is currently developing exhibitions about vintage tractors and space photography (though not the same exhibition, of course). Deadroads is her debut horror novel from Night Shade Books. She is working on an alt 18th century dark fantasy about elections. She lives in Ottawa, Canada, with her criminologist husband.