HONORABLE MENTION, SUMMER 2018

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

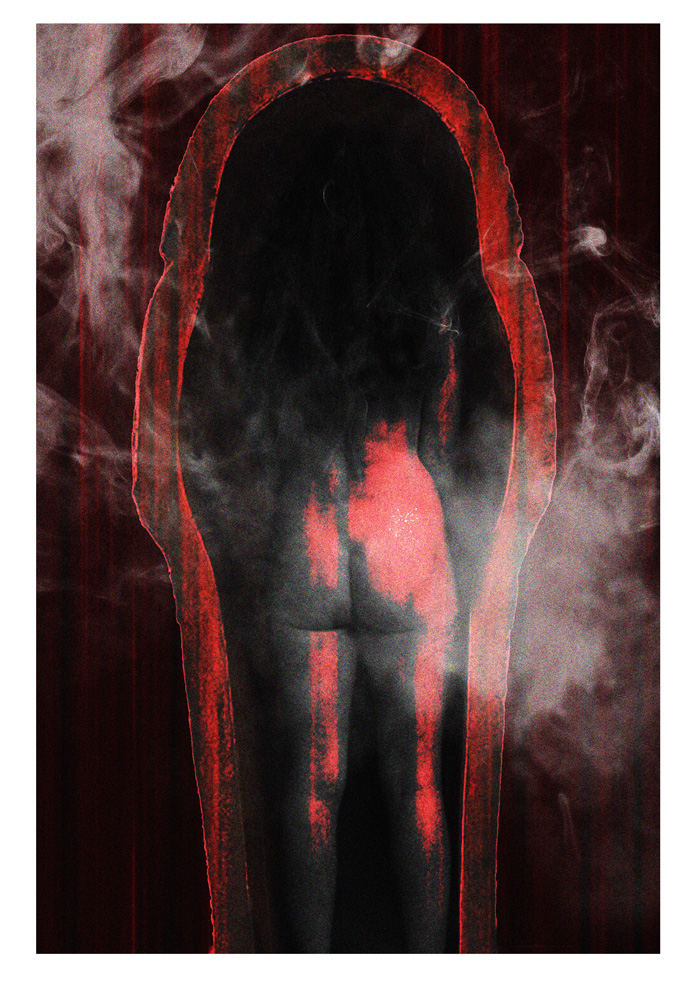

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY PAT RYAN

Dr. Desiderare was 95 when I last saw him. He called one morning and asked me to meet him for lunch at Sardi’s, for old times’ sake. But first, he said, would I jog downtown and pick up a box he had in storage. It was to be a gift for me, “a treasure of inestimable value.”

I had to rent a small van to transport the gift to my office on 47th Street, just off Broadway. When I realized my birdcage elevator wasn’t big enough for the box, I was ready to abandon it; that is, until the super came by. He circled the crate, scowling and shaking his head. “You can’t leave this thing in the lobby. It looks like a coffin,” he said. Then Dr. Desiderare arrived.

Dr. Desiderare, Doc to his friends, had a way about him, an air of gentle nobility. When he looked you in the eye, you almost bowed before hastening to help him. The super got a crowbar, and we dismantled the crate. Then the three of us stood looking at what was inside: a wooden box shaped like a telephone booth painted with Egyptian symbols. The front was covered by a red velvet curtain.

“This, my friends, is the legendary gazeeka box,” Doc said. “Rodney, it’s all yours now.”

The super and I heaved and cursed and maneuvered it into my third-floor office, where it took up 75 percent of the space.

“Compact little place you’ve got here,” Doc said.

“I don’t need much room,” I said. I explained that I was the writer, editor, and publisher of Rod’s Rialto: Theater Tips and Tidbits, an online website and blog for actors and tourists, though I print a few hundred paper copies for hotel lobbies and anyone who’ll buy an ad. I inherited the business from my father, who had been a Broadway press agent, and my grandfather, a booking agent in the old vaudeville days. Granddad had been a Runyonesque character, well-known around the theater district for his hand-painted ties and feathered glen-plaid fedora.

“Because your grandfather, rest his soul, was a good friend, I feel a certain responsibility toward you, son,” Doc said. “Your grandfather would not like to see you stuck in this gloomy room with only one small window, which, I observe, is nailed shut. You’re what, 30? No wife, no girlfriend, not even a secretary.” He was about to elaborate, but I squeezed past the box and out the door. A few minutes later, Doc emerged.

On the way over to Sardi’s, I concentrated on keeping in step with the slow taps of Doc’s walking stick on the pavement while I ticked off the highlights of his biography in my head.

As a teenager, Dr. Desiderare—born Theodore Galenus—had managed the sound and light effects for his parents’ burlesque skit: “Squeezer and Cleoprattler.” In his twenties, Doc moved on to the vaudeville circuit and traveled around the country doing monologues and impersonations. He was a handsome young fellow, for a time dating Gypsy Rose Lee, later marrying the Ingenious Gigi, a showgirl who’d followed in Gypsy’s footsteps as an “intellectual stripper.”

When vaudeville died, Doc revamped part of the old burlesque routine. He dropped the bawdy jokes, baggy pants, banana peels, pickles, and seltzer water and devised a magic act geared to cocktail bars and nightclubs around New York. Employing a burlesque prop, the gazeeka box, he would select a young man from the audience, someone who claimed to be seeking the “perfect woman.” He’d bring the man onstage and ask him to describe his ideal. Then with music, lights, and a waft of smoke, he’d abracadabra her into the box, pull the curtain, and out she’d step, to great applause.

A reporter once asked Doc what happened to the matched couples after the performance. Doc refused to acknowledge the reporter’s wink, saying, “I supply the natural beginnings, the happy endings are up to them.” In the newspaper, the type beneath his photo read: “I’m like the moon that brings the tide to the shore and then pushes it away to mingle with the sea.”

My grandfather told my father about Doc’s shows, and my father told me about them. Somehow, he said, these “gazeekas” always fit the men’s descriptions. My grandfather was puzzled because, though he knew his way around the available female acts of the day, he could never find out where Doc got his gazeekas. Doc insisted that they were spirits he had materialized from the great beyond.

“It’s all part of the cycle of life and death and life,” he’d say. “Think of it. Every day, millions and millions of human microbes are decomposing and recomposing.” He said he’d been studying Professor Einstein’s opinions on the reality of time and space, while simultaneously delving into Dr. Freud’s theories on desire and fantasy. In a letter to Granddad, he declared: “Though I am by trade merely a practitioner of optical illusions, I have been in tireless rehearsals alongside the forces of nature. As a result, when conditions are favorable, I am able to recycle carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur, and sculpt them into desirable female forms.”

Granddad and Dad never bought it, and neither did I, for we all knew showbiz folks too well. But back then, many people believed Doc. Now I wondered what he was up to. Once we settled at our table with our drinks, I prodded him to tell me more concerning the gift of the gazeeka box.

It was a sticky September day, and Doc’s face was flushed from the walk. He removed his suit jacket and loosened his tie. “First, I must tell you about a man,” he said.

I signaled for another round of drinks.

“There I sat,” Doc began, “in my cottage on Shelter Island, reflecting on the follies of humankind, especially the male animal, when I was visited by a man who desired that I perform my renowned magic act one more time, exclusively for him. The guy was 60 years old, educated accent, three-piece suit. He offered me any amount if I’d do it. Well, I named the highest price I dared, and it was accepted. The only condition was: I had to find a woman who met his exact specifications. He handed me a photograph and said her name was Leta.”

“His ideal woman,” I said.

“That’s right,” Doc said. “I thought the guy was pulling my leg, so I had my buddies check on him. Turns out the man, Mr. John Wayne St. John, was foursquare, legally, that is. He’d been a successful investment banker but had quit suddenly, surprising his colleagues. They said he’d dropped out of his social circle too, though no one seemed to miss him. He’d had a reputation as a womanizer, always dated much younger women, girls in their twenties, but he never married. The women we talked to said they felt he was ‘trying out’ his dates, measuring them up against someone. He was boring, they said, and demanding and jealous. Creepy but not criminal.

“Finally, I asked Mr. St. John what kind of woman I was supposed to produce, not her body but her soul. ‘A replica of my special girl,’ he said, adding, ‘Leta reminded me of that Tinted Venus statue I read about: blue eyes, blond hair, flesh like warm ivory, barely pink—a body of flawless symmetry.’ Those were his exact words. Seems they had been high-school sweethearts, but he had lost her through his own misconduct. ‘It was my sexual madness,’ he said. I can quote him: ‘She was pure of heart and body, but I had seduced her by promising to marry her. Then I turned my eyes on another girl—briefly, but long enough to lose Leta.’ He was sobbing as he finished. ‘She died, died of a broken heart, everyone knew it,’ he said. ‘She was not yet 20. She was a goddess.’

“When I asked if there’d been other women in his life, he said he’d found that all women are fickle. ‘Faithless, inconstant, immoral, jabbering creatures,’ he said. ‘The younger they are, the more excuses they make to stand me up. The more beautiful they are, the faster they leave.’”

Doc turned to me. “Rodney, you must understand the situation,” he said. “I’m not claiming that I thought well of the man, but I accepted the job for $50,000, $25,000 in advance. We shook on the deal, and the date was set, a year ago today. I located my original gazeeka box—the one now adorning your office—in the basement of an old opera house, cleaned it up, rented a stage in a soon-to-be-renovated nightclub, and had my costume dry-cleaned.”

I rattled the ice cubes in my empty glass. “Somebody was taken to the cleaners,” I said. “What the blazes happened next?”

“Vibrations happened. The vibrations of our energetic essences,” Doc said. “What an act—it’s not burlesque, it’s not vaudeville, no sir, it’s poetry.” He smiled. “Your old magician was simply marvelous. Yes, the gods favored Dr. Desiderare that day. Somewhere, Ovid was smiling.

“To my audience of one, I proclaimed: ‘I bring you the Pygmalion fantasy: a ravishing and malleable Galatea who never forgets that she owes him the breath of life.’ With Borodin’s symphonic ‘Sands of Time’ on the record player, I flowed away and returned amid scented fog, wheeling out the cabinet with the sign ‘The Gazeeka Box of Dr. Desiderare.’

“I drew the suitor closer and whispered, ‘This box was discovered in the tomb of an Egyptian king. I have genuflected before it and performed the ancient rites of all the gods of love. Inside is the goddess of your dreams, your fair lady. Do you accept this woman?’

“John St. John replied: ‘If she is a copy of my Leta and will be faithful to me, I vow to marry her.’ He put his hand out to pull back the curtain, but I stopped him and said, ‘You must not break the vow you have just made, or you will regret it the rest of your lonely days.’

“Then John asked me, ‘Do you swear this is the spirit of my Leta?’ I swore that I did. ‘Then I will marry her today,’ he said. ‘Come forth, be my wife.’

“I drew back the curtain, and a woman came forth: a bespectacled, white-haired woman in jodhpurs, a riding crop in one hand. She did have blue eyes. John raged. ‘This woman is not my Leta. She’s 40 years too old and 40 pounds too fat!’

“The woman laughed. ‘And 40 degrees smarter than you.’

“I held out my palm and said, ‘I’ll take the rest of my fee now. I delivered your 19-year-old girl as she would be today. Her hair is no longer blond, but there’s a lot more in her head. By the way, she’s passionate about horses.’”

I played the straight man, saying, “Don’t tell me he married her.”

“He did,” Doc said. He pulled a newspaper clipping from his wallet. “But as fate would have it, the newly betrothed Mr. St. John died one month ago after a horseback-riding accident. Here is his obit. Read the last line.”

I read: “John Wayne St. John is survived by his faithful wife.”

We finished our lunch, our coffees, and our brandies. “This is goodbye, son,” Doc said. “Tonight I’m flying to the Bahamas with Gigi, my indispensable commingler. All our affairs are in order. My lawyer has my will, but I wanted to give you the gazeeka box personally.”

After he paid the bill, he honored me with the royal gaze. “Do what you will with the gift, but treat it with respect. It is not only a memento of your friend the great Desiderare, it is also a means to add zest to your routine existence.”

I helped him into his jacket, and we walked out to 44th Street, where he paused and looked up and down. We’d spent more than three hours in Sardi’s; it was now early evening, and the theater marquees were lighted.

“Ah, soiled, seductive old Broadway. Part of me hates to leave here,” Doc said. “Think of the billions of microbes whirlpooling up through the grates from the labyrinth of subways below to the alphabets of neon lights above.” He sighed. “But alas, winter is coming.”

He hailed a cab with his walking stick. One pulled up instantly, and I opened the door. As he got in, he said, “Good luck with your gazeeka.”

“Doc, there’s no such thing as the perfect woman,” I called to the retreating taxi. “Who said I’d want one anyway?”

It wasn’t until the next morning that I had the courage to face my office again. I climbed the stairs mechanically, but I’d forgotten that the gazeeka box was right behind the door, and I pushed it open too hard. The door hit the box, sprang back and knocked me unconscious. When I came to, bright sunlight was shining through the open window; a pleasant breeze was swirling scented mist around the room. The gazeeka box was tipped on its side, and to my surprise, I was lying inside, snug and comfortable, no aches or pain. A cool hand caressed my brow. I opened my eyes wider and looked up into a woman’s blue eyes.

“I’m Leta,” she said. She was exactly as described by Doc. I noticed that her dress was fashioned out of the red velvet curtain that had covered the front of the gazeeka box, belted by the gold pull cord with tasseled ends that curved around her hips.

“Nice to meet you,” I said.

“I’m so happy to be out of that box,” she said. “I’d like to go for a walk now, breathe fresh air and stretch my legs.”

Feeling light-headed, dazzled, and a bit foolish, I stood up as nimbly as I could, opened the door—carefully—and said “After you.”

We headed toward Central Park. We didn’t speak, our steps were in sync, the crossing lights were green. At Grand Army Plaza, we stopped in front of the Pulitzer Fountain and looked up at the statue of Pomona, Roman goddess of abundance, offering her basket of fruit.

“Rodney,” Leta said, “isn’t there something you want to ask me?”

“Yes, Leta, there is one thing. How do you feel about horses?”

Pat Ryan’s writing on movies, music, and literature has appeared in The New York Times, where she was an editor in the Culture Department. Her novel Marilyn & the New York Itch won second place in the Del Sol Press 2017 Prize for First Novel, and her mystical Hebrides story, “Two on the Isle,” was published in the 2018 American Writers Review/San Fedele Press. She is writing a novel-in-stories about the animated residents of Cutlery Falls, Vermont. “The Gazeeka Box” was inspired by Ralph Allen’s The Best Burlesque Sketches, Gypsy Rose Lee’s The G-String Murders, and the Perelman-Nash-Weill musical One Touch of Venus.

Pat Ryan’s writing on movies, music, and literature has appeared in The New York Times, where she was an editor in the Culture Department. Her novel Marilyn & the New York Itch won second place in the Del Sol Press 2017 Prize for First Novel, and her mystical Hebrides story, “Two on the Isle,” was published in the 2018 American Writers Review/San Fedele Press. She is writing a novel-in-stories about the animated residents of Cutlery Falls, Vermont. “The Gazeeka Box” was inspired by Ralph Allen’s The Best Burlesque Sketches, Gypsy Rose Lee’s The G-String Murders, and the Perelman-Nash-Weill musical One Touch of Venus.