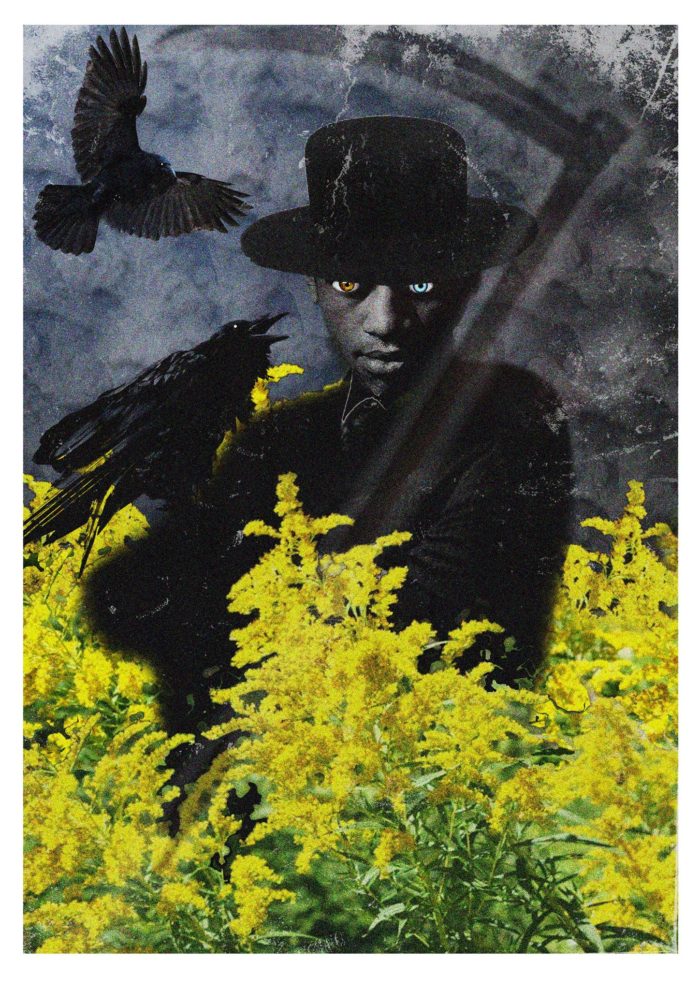

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

HONORABLE MENTION, Summer 2019

BY LEONARD ONIONHOUSE

There were four lights in those days; four lamps that lit the farm country of my youth:

The greater light of the Sun,

The lesser light of the Moon,

The pearl glow of Kerosene, and

The dim flicker of Candles, vague and shadow-wrought.

Electricity was a mere curiosity that we read about in the papers. The cities blazed with arc lights and incandescent bulbs. But on the prairie we had few barriers to the dark. And when night came, it settled in with the immensity of an ancient flood.

I was thirteen that summer. A thin and silent, black-haired boy. Yet, a strangeness gathered in me. An odd quickening in the blood that I felt and that I feared. Mother noted it soberly, as she scrubbed me in the galvanized metal tub. That black mop of hair, so wild and resistant to combing, was no longer confined to my head. Manhood had begun to creep into my flesh.

Ours was a small family. Father, Mother, Sister, and I, in that lonely clapboard house. And a brother, drifting dust-like in the memory-haunted quiets. Dead ten years and still his fingers traced fresh lines on Mother’s face.

Typhus took him. Typhus: that name like some mythic Greek king. Typhus, lord of drawn curtains and darkened rooms, of camphor and soiled linen. Typhus of the tiny caskets. And now Typhus had returned . . . or was it something else? Cholera perhaps. Or Diphtheria. Or another, more dreadful death. The rumors were indefinite. We only knew that sickness stalked the prairie, stealing away the living, leaving corpses in their place. And neither prayer nor medicine could assuage it. Families sought refuge in isolation. The farms grew into islands. Back in that distant plague summer, west Kansas became an archipelago of quarantines.

I was surprised then, to see the wagon coming toward us on that bright June morning. I watched it from the fence line where I crouched, tending to the barbed wire. A mule-drawn buckboard, covered in a canvas arch like a miniature conestoga. A shadow seemed to drive it, a figure so black it looked like a man-shaped hole in the air. I remembered my dead Granny’s tales of the dark faeries and the nookel-folk who slip between worlds. I paused from my tools and closed my eyes. I counted to ten. But when I looked again, it was still there. This shadow-driven wagon, wobbling through heat-rippled fields.

In the tall grass, I was invisible. A small, obscure thing. Yet the wagon trundled straight to me, as if taking my obscurity for a beacon. The mule shuffled to stillness in the grass. The driver looked down.

“A boy?” he said. “ Or is it something more?”

I stared at him. His clothes, his skin—both black as a King James Bible. I did not know men came in such a color. And his eyes: one icy blue, the other solid gold. I could not look away.

“The sun is a ball of burning brass,” he sang. He winked his eye, turning it from gold to silver. “The moon is a plate of tin.”

He winked a few more times, the strange eye shifting from silver to gold, from gold to silver. Flashing revelations of the magic in his head. He smiled, a crescent moon of teeth. I wanted to laugh. I thought I might scream. Then he stopped his smile and sniffed the air.

“A storm is coming,” he said, looking behind him. “Close on my heels.”

I stared at the sky, hand to brow, visoring my squinted vision. It was blue and brilliant, adorned in milkweed wisps of cloud. I turned in a circle, scanning the whole vault of heaven. I had never seen a less threatening sky.

“It’s coming all right. An infernal tempest.”

A huge raven hopped up from behind him, flapping to his shoulder with a squawk. He fingered a few nightshade berries from his pocket and fed it absently. A second raven slipped out from the wagon’s canvas to beak its share of berries. But the wagon driver paid no mind. His eyes and ears roved elsewhere: across the field, back toward our house, where the screen door wheezed and slammed. I watched him watch my father emerge into the barnyard, looping one overall strap onto his shoulder.

“Hmm,” the driver grunted. “Dissolution. I read it in his stride.” He sighed and looked again at me. The eye of blue, the eye of gold: I felt the calm dissection of their gaze. He shook his head. “The burden falls on you, son.”

He plucked out his gold eye, gave it breath and buffed it on his sleeve. He tossed it and I snatched it like a falling apple. I turned it in the sunlight. This small gleaming globe—half gold, half silver. Or was it brass and tin, like the sun and the moon?

“Our salvation lies in shiny trinkets,” he said, pulling a fresh eye from his vest and pushing it into the vacant socket. He squinted and blinked, and I watched as the new eyeball rolled in his skull. Then it locked into alignment and fixed on me, both eyes matching now in a blue-eyed stare. He pointed to the ball in my hand.

“Plant it deep in the marsh. Then piss on it. This and every day for twelve days, that it may grow fruit. Off with you now, Sunny Jim. The dread hour grows near.”

And off I was, toward the marshlands bordering our fields. The thought of doing otherwise never crossed my mind. I was an obedient child, but it was more than that. It was those eyes, burning in me like blue furnaces. Behind me, the wagon stirred and ambled toward the barnyard, where Father swayed in a blinking liquor-stink.

That evening at dinner, after grace was said and we’d begun to eat, Mother paused above her plate to stare at Father. He didn’t seem to notice. He was busy gazing at some grease stain on the wall, chewing his ration of stale bread and potato.

“What business did you have with that peddler this morning?” she said.

Father slowed his chewing, swallowed, and knit his brows in what might have been irritation, or might have been the labor of recollection.

“I,” he cleared his throat. “I bought some seed off’n him.”

“What kind of seed?”

He blinked. “Corn, I think.”

“You think?”

“Wheat,” he said, then repeated it more firmly. “Wheat. We’re putting wheat in the north field this year.”

“It’s late to be planting,” Mother said, in her ever-joyless tone. “Should have had the crop in a month ago.”

“It’s hybrid seed,” Father said. “Made by Germans. Grows fast and scarce needs tending. You needn’t even break the ground. You just scatter it by the handful. God and nature do the rest.”

“The peddler told you this?”

“Yes.”

“And you believed him?”

Father glared. He was not above belting her when she rode him like this. But fatigue bridled him, his strength drained by last night’s drinking.

“The boy and I will have it in tomorrow. Before noon.”

“And what did you pay for this sack of magic seed?”

“One silver dollar. A bargain.”

“A swindle,” said Mother.

The next morning came and went with no sign of Father. Then, about two in the afternoon, he appeared, stumbling from the corn crib where he’d spent the night in blissful distance from his wife. I helped him hitch the wagon and we drove out to the north field. I walked beside Poor Richard (our old half-blind pony) as he pulled the rickety wagon over untilled ground. Father lay in back, tossing seed from a large tow sack. He was unusually merry: singing lewd songs between tugs from a white jug. Seed was not the only thing he’d traded for. He offered me a swig but I declined. Mother always warned me off of drink. He shrugged and smiled. None for me meant more for him.

Thus passed the afternoon and much of evening. Poor Richard and I in an endless trudge; Father in his private revel. He drank and laughed, sowing seed in wild fistfuls. Such strange seed, resembling no wheat I’d ever seen. A yellow dust that burst like quiet conjurings from his hand. I wondered what would come of it.

I had not long to wait. Father was right: that tow sack seed sprouted swiftly, without tending. In two weeks’ time the whole north field was crowded. But not with wheat. Goldenrod is what the soil brought forth. Goldenrod, that brilliant yellow bane of farmers’ fields. Fence line to fence line it ran in blazing riot—drinking in the solar floods of summer, pushing skyward even as we watched.

“Fool,” Mother said.

Father said nothing. There was nothing to say. He knew that, short of setting it on fire, there was only one way to rid a field of goldenrod. Stalk by stalk, we’d have to pull it up. Stalk by stalk, till our backs sang with despair. But it could be done. It was not impossible. What’s more, it had to be done. Father squared his shoulders, set his jaw . . . and slipped off to the corn crib for another long communion with that jug. It seemed to have no bottom.

And so the languid days went by. The season deepened to midsummer; the goldenrod reigned unchallenged in the field. Secretly, I welcomed that acreage of yellow light. When chores were done and I could evade my mother’s eye, I’d slip off to the north field the way Father slipped off with his jug. And I’d lay (sometimes for hours) amid those lovely weeds, feeling the green mingling of sun and soil. Those were my last bright days. Before the quarantine was breached. Before old Grunkel came.

One chilly evening in late August, we gathered for supper. All of us but one. Father’s chair stood empty.

“Where Da?” Sister asked. She was seven but still unfluent. Something misshapen in her mouth (or brain) deformed her every word.

“He’s gone to fetch your great uncle,” Mother said. “Great Uncle is going to live with us now. He is old and needs looking after.”

“Grunkel?” Sister said.

“Great Uncle,” Mother said. But Grunkel was the name that stayed with me.

The evening was full dark with Sister tucked away, when we heard the creak and hoof-shuffle of the wagon. Mother and I went out to meet it. In the ruby-glassed glow of the hurricane lamp we watched them roll up the drive. Father slouched at the reins. Grunkel wrapped in a quilt beside him, milky bald head poking out like a pupa, eyes wide and wandering.

We kept him in the shed that night. He had a smell, a sort of dry putrescence, too vile to let in the house. Father arranged a bed for him out of hay and an old canvas tarp—things we could burn without loss. He’d be comfortable enough, Father said. It wasn’t that cold. Besides, he was too senile to know the difference.

The next morning, I dragged out the metal tub and helped Mother fill it. Steaming kettles of water, chilly pails from the well. Grunkel stood by, wrapped like an Indian in that filthy quilt, watching us.

“Go ahead now,” Mother said, pointing to the tub. Grunkel didn’t move. She prompted him again with scrubbing gestures, and slow words. “You need to clean yourself. You need to wash.” Still, he did not move. She sighed. “Give me a hand, son.”

I touched his shoulder, moving him forward with a gentle push. At the tub’s edge Mother slipped off the quilt. A rank odor spilled out of him—a humid broth of excrement and spoiled meat.

“Lord!” said Mother, cringing. I wanted to wretch. It was the foulest smell I’ve ever known. His flesh though, was unspotted. Immaculate in its bloated baldness. With gentle pushes and pulls, breathing all the time through our mouths, we got him into the tub and Mother set to work. Gradually the smell abated, dispelled by soapy water and the morning breeze. Gleaming wet in his hairless white skin, he looked like a swollen infant. Blinking, expressionless, a blank slate of innocence. Then a change came over him. His black marble eyes flickered as if awakened from a spell, and his mouth curled into a wide grin. I stepped back. Those teeth: too large for his head, too sharp and evenly assembled. The jaws of a prowling carnivore. He was staring at the house. I followed his gaze to the second story, where Sister’s face peered from a window.

“Oh Jesus,” Mother gasped, dropping the scrub brush. I looked back at the tub. Something purplish poked from the gray water between Grunkel’s knees. At first, I took it for a turtle’s head. Mother splashed it with a nearby pail, as if to cool a fire. But the purple-headed beast swelled defiantly, growing another inch. Mother shrieked and ran into the house.

It was left to me and Father to finish the bath. Rinsing, drying, clothing, gingerly maneuvering around “that thing” as Father called it. “Christ, look at that thing,” he laughed. “Like a goddamn donkey.”

Life settled down after that. The days found their routine. We put our lodger in the room under the stairs. Small, windowless, more of a closet than a room, but there was space enough to fit a cot. Sufficient for a creature who spent his days in staring silence. He never went outside, only leaving his room for meals, and rarely doing that. He ate little and passed nothing. Morning and evening I found his chamber pot full of dust and spiderwebs, as if those were his sole excretions. And slowly (like a change of seasons) his smell began to resurrect. The dry rot fecal-creep that murmured of some buried crime.

Then came that starless night in October. The night the end began.

I woke in my attic room: the air black, the sky beyond my window like a lidded jar. I lay there exiled from sleep, feeling the blunt throb of my heart, the thick rivers of my blood. I listened to the dark. Night sounds, furtive and patternless. A creak, a knock, the dull tick of settling timbers—small stone-like notes in a black hiss of quiet. Then something else. A creak on the stair . . . there . . . and again. Who was it? A shadow sneaking up the staircase, padding softly past my parents’ door, down the darkened hallway . . . to Sister’s room.

I lurched through the dark attic, blindly groping, stumbling, knocking my head against a rafter. By the time I reached the ladder, the screams had already begun. High crystalline shrieks. I fumbled down the rungs. Father weaved half-alert toward Sister’s bedroom. Mother followed, candle in hand, casting light and lunging shadows. The walls danced like laughing devils.

“He bite!” Sister yelled, as Father burst through her door.

Over shoulders, through an elbowed jerk of arms, I saw the room. A brief candle-lit tableau. Sister, clutching herself in a corner of the bed. Grunkel, naked and erect, grinning with ferociously stained teeth.

Father was on him instantly, driving his fist into those teeth. They shot from Grunkel in a single piece—a disembodied grin, spinning monstrous through the air. I gaped appalled, knowing nothing of dentures. I thought old Grunkel’s mouth had left his head. I watched it snap and clatter across the floor, then stop and skitter imp-like beneath the bed.

“Hellfire!” Father shouted at the gash along his knuckles. Mother and I stood frozen, while Grunkel slipped into the hallway. Slinking off, as if he might return unnoticed to his room. But Father gave chase and caught him by the neck—angry fingers gripping mushroom flesh. They stumbled in a bum-rush and Father pitched him down the stairs. Dull thunders shook the house. The massive thumping weight of Grunkel’s fall. Father stalked after him. “Son of a bitch,” he growled. I thought I was about to witness murder.

I hurried down the staircase behind Mother. Quick candle-lit steps, fear hitching in my chest. Father stood in the kitchen. And so did Grunkel. I was stunned, expecting him to be, if not dead, at least moaning in a heap. But he was up and unmarked. Even that donkeyish appendage was intact—firm and fierce enough for me to read his pulse in it. Only his mouth had been diminished. Untoothed by Father’s fist, a well of flaccid darkness in that alabaster face.

Father was the wounded one. He weakened as I watched. “Get out,” he rasped. But Grunkel would not go. He was drawing off of my Father, draining him somehow. That larval skin, that erection punching into the air, that insectile silence out of which he stared—they all swelled like bloating ticks. And Father shrank, crouching to caress his bleeding knuckles. He had no fire left.

The burden falls on you, boy.

The black peddler’s words returned from that June morning, touching off a flame within my chest. And suddenly the candlelight was dancing in my eyes, blazing like sunlit brass. I knew what I must do. I stepped past Father. I stared at Grunkel. And with a slow unfurling smile, I took my fear and planted it in him.

He shrank back, wincing as against a great light, and darted out the door. For a moment, he was visible through the window. White flesh hovering like a ghostly flame. Then he was gone, swallowed in the moonless dark.

Father wrapped his bleeding hand in a linen strip and Mother returned upstairs to Sister. Grunkel had bitten deep into her thigh. I saw the mark: a deeply purpled horseshoe of jots and angles, like some ancient script. Mother comforted her, and soon she was asleep. As was Father. As was Mother, too. Sleep seemed to engulf the whole house, sealing it from the wakeful world. But there was no sleep for me. Not then, nor ever after. Like Grunkel, it had fled into the dark.

I kept a vigil on the porch: watching the night, waiting for the sun. Morning finally came, and mid-morning. Then in the bright fore-noon, I heard movement in the kitchen. A clatter of dishes, a shamble of feet. I turned and peered through the screen door. Mother hobbled weakly about the table in half-somnolent circles. When she saw me, she blinked and frowned.

“i need to make breakfast,” she said. “Or dinner . . . I think.”

Her face was washed out. Her lips had lost their hue. Her hair had brittled and blanched three shades. Even her irises had paled. A sickness had battened onto her—some slow thief of color. She stared at her naked feet, one of which was swollen twice the size of the other.

“Must have stepped on something . . . cut my foot.”

The fog in her mind. I wondered if she knew me.

“Well i reckon . . . i’d best get to bed.”

She limped back up the stairs, that breakfast she’d intended (or was it dinner?) left unbegun amid the cluttered table. I turned away and never entered there again. It was a pest house now, one of those leprous dwellings men abandon or burn. No physician could heal what lived in it. But I knew (somehow I knew) in the field there was a medicine, soon to ripen.

After that, I lived beneath the sky without sleep or food. The long fast gave me powers, blossoming my senses. New eyes and ears grew in me, new subtleties of touch and smell. Day and night I roamed the fields, circling always back to watch the house. But there was nothing to see or hear. Just a deep trance quiet, and (it came in random telegraphs) the muted click of Grunkel’s teeth. Sounding like the onset of some darkly clock-worked time.

One night, a patch of foxfire came alight out on the marsh. Some message there, I thought. Some signal in its flickering, though unreadable to me. And yet . . . I could read it, or something in me could. The new and secret animal I was becoming. I set off running through the tall grass, toward the long harp of barbed wire that fenced the field’s edge. I leapt over it and landed in the marsh. Dark seeps and tufted hillocks, small ponds of torpid water. There are no straight lines through a marsh. I capered over ankle-bending earth, making crooked paths, till I came to the source of that signal-flicker light. A brightly bladed scythe, growing like a sapling from the ground. Its haft was a curve of brazen wood, its blade a tinny gleam of moonlight. And I remembered the peddler’s eye, planted by me months before. Refashioned here by time and soil and twelve days’ watering. I took hold and pulled . . . and pulled . . . and pulled till it came free, white-knuckled roots still gripping earth. I turned it in my hand: this strangely razored tree. The peddler’s gift and burden. A scythe of brass and tin.

I returned to the farm, once more to keep my vigil over the house. Again: nothing to see, little to hear but sleep and stillness. And that soft infrequent click of teeth. Then on the seventh night, the faces came. Three yellow faces, round and rising like harvest moons in the second story windows. Bloated, hairless, watchful. A silent trinity gazing through the glass. And behind it, some malignancy—pressing, swelling, longing . . . to burst its sickness airborne.

Out of the north field a wind swept up. A chorus of green-tongued whispers:

The harvest . . . the harvest . . . the harvest . . .

The time of ripening had come. I took up the scythe and waded out into that hushed night sea of goldenrod.

The scythe swung whispering arcs. And with each stroke, each parting of bloom from stalk, I grew stronger. The field’s green life flowed into me. All boundaries seemed to fade—muscle and bone, scythe and goldenrod, joining in a single harvest rhythm. The blade-sweep pulse, the ancient dance of life exchanging one mask for another.

Forty acres fell that night. A three-day labor, yet it was scarcely midnight when I reaped the last thatch of goldenrod. Some great hand had stopped the moon and held the night’s advance. A ceremony was afoot, and yet to be completed. Until it finished, no sun would rise above this patch of Kansas. Earth and Sky decreed it. One final ritual to end the night . . . and the world would turn again. I shouldered my scythe, heading back across the field.

Fallen stalks of goldenrod carpeted my path. Withered, silver gray, all blazing yellow gone. In the gleaming scythe blade, I caught my own reflection, and thought I glimpsed a stranger. I was naked (how odd, I had been unaware) and my hair (all of my hair) had grown bright yellow. I recognized the harvest: the goldenrod’s scythe-severed field. All that it was, was in me now. I was the house of hundred sunlit days.

Atop the barn, I found them waiting. Those bloated faces, luminous with jaundice, hovering above three frail and wasted bodies. Unglassed now, and in the open air, they stared down from the rooftop. Father, Mother, Sister: transfigured and arranged there like strange weathervanes. I nimbled up to meet them, scaling the barn’s gray wall with effortless magic.

The Father-thing approached me first, unpocketing Grunkel’s teeth from half-slack overalls. They chattered in his open palm. With his other hand he beckoned me in languorous invitation. As if to say:

Come on boy, take on the sickness, join yourself to his rapturous disease. . . .

Then the nightgowned Mother-thing was at me from behind. A fluttered rush of gingham flower-print to drive me toward those teeth. I leapt and spun and let the whirling scythe pluck off their heads, pop-pop, like gently decapitated dandelions. The headless overalls did an awkward jig and tumbled off the roof. The nightgown staggered after, joining its fellow carcass in a patch of barn-side nettles. But those severed heads floated upward. Still twitching, still blinking, still working mouths in dull astonishment. Bewildered balloons, sailing off into the sky. Till a pair of winged shadows swooped out of the dark and snatched them from the air. The peddler’s ravens, the nightshade eaters, returning to devour these ripe plague berries.

Only the Sister-thing remained, along with Grunkel’s grin. It went before her like some toad familiar. Languid hops, brief chattering pauses. A dream-like advance, hypnotic in its rhythm. Then it lurched with sudden speed, a ravenous, snapping blur. I jumped back, muscle acting before mind, and drove the scythe straight into Grunkel’s teeth. They shattered like a tea service, bouncing off the roof in porcelain shards.

Now the Sister-thing stood alone, immobile as a rooted plant. A small un-petaled flower, blooming its stark face atop that barn. I paused a moment to ponder. Did a residue persist? Was my sister in that head? Was the simple, harmless child shackled within that brain? And if she were, what grace could I bestow? What deliverance, but to make of her an offering to the ravens? I raised my tin-bladed scythe.

With a spasmed jerk, she drew a corn-knife from her nightshirt. A rusted iron crescent. I tasted its pollution, the tang of it on the air—the metal sweat of tetanus, the quiet rot of gangrene. She poised it like a hairbrush, then swept it back upon herself, slicing off the top of her head. A clean cut just above the eyebrows, plague-softened bone giving way like cheese before the knife. Dust plumed from the uncapped skull, roiling up like chimney smoke, emptying the Sister-thing of substance. She shriveled swiftly and was gone, like a candle blown out. Just a rumpled nightshirt left to drape the shingles. And the wind took that.

Overhead, the dust cloud swarmed in seething silhouettes. Matter seeking form, till it shaped into a dragon. The dragon circled silently, two orbits of the barn. Thereupon it winged off westward as I stood and watched it dwindle against the stars. Then I descended from the rooftop to begin my final chores.

There was no kerosene. A few cupfuls in the house perhaps, but I could not go in there. The pestilential embers still crackled in its walls—lingering in the timbers, brooding through the slow dust of those rooms. So I rooted in the corn crib till I found my father’s jug. The one the peddler gave him. The one that never emptied of lost hours. I pulled the cork and took a swig. It tasted of fire and sorrow. It tasted of summer’s end.

I doused the farm: the house, the barn, the sheds, the dry grass and brambles, the headless carcasses lying crooked in the nettles. Then I took a single match . . . and I set it all aflame.

And that was the fifth light: that jug-liquor sun, roaring on the prairie. The last ecstatic lamp in the country of my youth.

____________________________________________________________

Leonard Onionhouse was raised in rural Wisconsin, the ninth of nine children and the seventh of seven sons. His earliest memory is of chasing a gray cat through the corn. As a boy he aspired to be a tap dancer. As a young man he left the farm and snapped on a blue collar, never to relinquish it. He spent fifteen years as a long distance truck driver, enduring all manner of traffic and inclement weather. Now he’s a janitor, and cherishes the peace and quiet of his work — the stillness of vacant buildings, the slow routine of emptying wastebaskets. He is a lifelong insomniac, but regards insomnia as his muse. For it was in those sleepless, solitary hours that he taught himself to write. “Sun of Brass, Moon of Tin” is his first published work, though he has written one (as yet unpublished) novel called The Marigold Plate. He still lives in Wisconsin, along with his wife and young daughter. They are the treasures of his heart. And he has a website: leonardonionhouse.com

Leonard Onionhouse was raised in rural Wisconsin, the ninth of nine children and the seventh of seven sons. His earliest memory is of chasing a gray cat through the corn. As a boy he aspired to be a tap dancer. As a young man he left the farm and snapped on a blue collar, never to relinquish it. He spent fifteen years as a long distance truck driver, enduring all manner of traffic and inclement weather. Now he’s a janitor, and cherishes the peace and quiet of his work — the stillness of vacant buildings, the slow routine of emptying wastebaskets. He is a lifelong insomniac, but regards insomnia as his muse. For it was in those sleepless, solitary hours that he taught himself to write. “Sun of Brass, Moon of Tin” is his first published work, though he has written one (as yet unpublished) novel called The Marigold Plate. He still lives in Wisconsin, along with his wife and young daughter. They are the treasures of his heart. And he has a website: leonardonionhouse.com