WINNER, FALL 2019

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

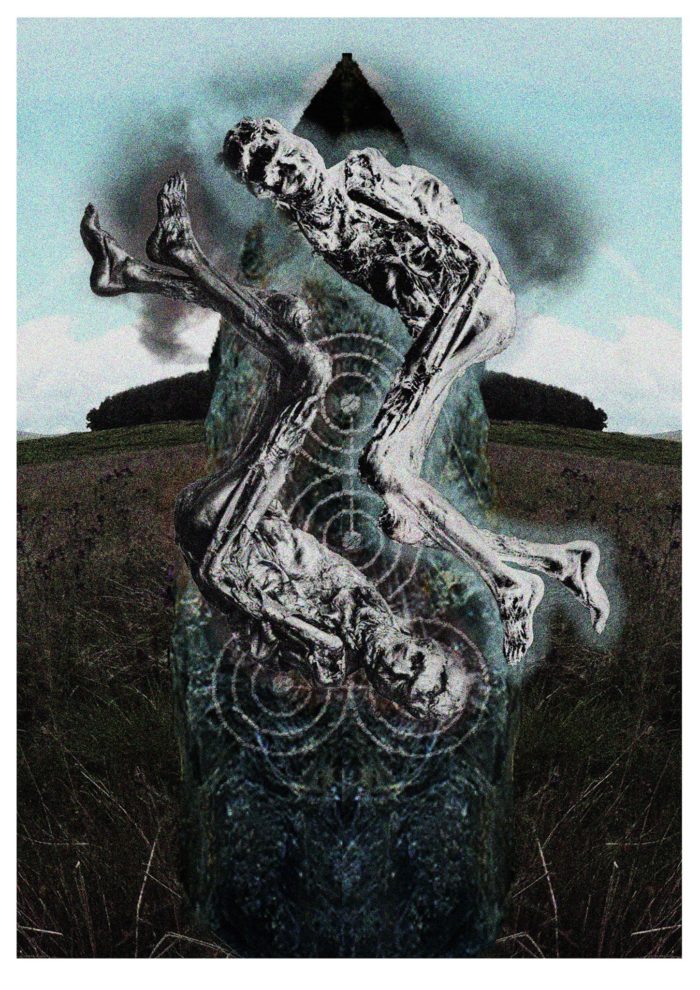

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY ROWAN BOWMAN

Before this was Northumberland people lived here on Goatshill Crag. They looked down on the Moss and carved symbols into the rocks.

I have been coming here since I was a boy. It is a peaceful spot. Even when hordes of schoolchildren trek across the raised bog with their worksheets flapping on their clip-boards, there is a quiet about the place. The Moss affects the acoustics of the valley, smothering sound. Here among the rocky outcrops there is only the perennial sea breeze playing through the bracken.

I watch them far below while I am safe above.

There are so many prehistoric rock carvings in Northumberland that they can’t all have been catalogued. I am always on the lookout for a stone which no one has recognised before. Some can only be seen when the light is low and slants across the rough stone. With some you need to spill water onto the surface to distinguish the pattern from the lichen. The symbols are neither abstract nor accidental: they are a communication left for those too far away to hear a call, too far away by four thousand years.

It was a hunger to interpret the carvings that got me into archaeology. I have a small team of commercial field archaeologists, mostly working in the North East of England. Whenever a project needs an archaeological report we provide it. We dig for a few days, usually no more than two, write our report and move on. My specialism is prehistoric rock art but I have only been called upon to test it once in the twenty years I have been digging.

I can see the place from here, where the track runs through the trees to the new visitor centre.

She was there that first day, doing an impact assessment of the new road for her Countryside Management degree. A first-year student, though she looked much younger, a child, still. She was called Annie. I never learnt the names of the others. She wore shorts and her legs were pale and goose-bumped that morning in the mist. Her nails were bitten. Her arms were sunburned right up to the sleeves of her t-shirt. I never looked directly at her face. They told me later that her eyes were brown. I got the impression of freckles.

The rock had been discovered by one of the engineers working on the construction site. It had not been mapped before and lay in the path of the new road. It was next to the plantation beyond the lag, but it would once have been in the bog itself. They cut peat here until the end of the last war. The rock was about a metre long and seventy centimetres wide and the same high, in a rough lozenge of weathered sandstone. It had a network of intricate motifs, worn so smooth by time that they were best seen from rubbings. I must have walked past it a hundred times; it was only a couple of hundred yards from where I usually parked. I wished I had found it.

The day had started smoky-blue with mist from the coast meeting the burning heather in the distance. The September sun broke through the haze well before noon. It burned my neck as I worked. Jo said I crooned while I made the rubbings and sketches, stroking the sandstone to sooth it. She suggested I should try treating a woman like that. I hate it when she attempts to engage me in banter but she won’t give up.

There were six students in Annie’s gang, three youths and another two girls.

The boys had given up trying to attract the girls’ attention and stood aloof in a bachelor group. Maybe Gunner’s graceful charm and William’s rugby-playing bulk thwarted them. My colleague, Dr. Rendell—Jo—is not the sort of woman you flirt with. The lads had no incentive to hang around so they drifted off to smoke at the edge of the plantation.

The other girls were bold, not shy like Annie. They flirted with Gunner and William all morning. They left me alone. I wondered if Jo had explained about my difficulties.

Jo watched me, saw me watching Annie.

I bent my head and concentrated on my work.

The rock had a higher density of ring motifs than I had seen before out here on the Moss, all cut with diametric grooves. The carvings were consistent with late Neolithic or very early Bronze Age rock art. That meant the artist knelt where I did now four thousand years ago. The close contact with the distant past made the hair stand up on the back of my neck.

When I had finished Annie came over and studied the rubbings in silence for several minutes, then said they looked like “no entry” traffic signs. She traced the patterns on the stone with her small, blunt fingertip and shivered.

Gunner photographed the carvings with the care of a forensic scientist. William sat and drank tea from his thermos and calculated how long we could spin the job out. There seemed little likelihood of it lasting a second day. Jo forgot the students weren’t there for the archaeology and lectured them until they fidgeted irritatingly in my line of vision.

Annie would not come near the rock after that initial examination. She took photographs from a distance but avoided it all morning. I had seen the fascination, the way her breathing changed, the way she touched it, yet what held me in thrall obviously upset her. She settled a stone’s throw away on the bank-side in the sunshine glancing periodically over her notebook. The urge to say something to her kept pumping adrenaline through me. Each time as the hormone drained away like an outgoing tide I was left further and further away from the ability to communicate with her.

The morning wore on. I finished my notes while we waited for the County Archaeologist to give permission to move the stone three metres to the right.

We ate at midday. I rested with my back against the rock. The other two young women sat nearby and chatted to William. Their voices drifted over me. Down here, next to the bog, the heat collected in the sheltered hollows. The sky was blue above us. A quiet descended. Their voices dropped by unspoken consensus to a murmur that mingled with the drone of insects. Even the birdsong ceased. Then Annie was bitten by a horse-fly on her smooth, white thigh and made a fuss. I rummaged in one of our boxes of equipment and walked over to her with some antihistamine cream. She thanked me and took the tube without looking up from the tiny prick of blood. I was uneasy, anxious now that she was avoiding me, rather than the stone.

Everyone on the Moss that day came to see the rock being lifted. It was not a fragile artifact, but it weighed over a ton and needed to be repositioned precisely in its original alignment.

I was the only one not taking pictures as the stone was raised. I wanted the closeness of direct observation without a camera lens between.

I saw him first, lying in his grave beneath the rock. His black, bony shoulder twitched as the weight was lifted.

Annie screamed.

I shouted, “Hold!”

The Bobcat jerked to a standstill, the rock swaying a foot above the body. There was an intake of breath and then a general groan. The last thing anyone wanted on one of these jobs was to actually find something. But then, what a find.

The rock was swung away and carefully re-positioned. William plotted and recorded a trench around the grave. The police pathologist said it was unlikely he’d got that colour from a sun bed, and gave us leave to exhume him at our own pace. William cajoled sufficient money for us to use carbon dating. The students stayed for the afternoon, basking in the sunshine.

I knelt with my pointing trowel, paintbrush, and dustpan and began to pick him out of the soil.

It quickly became obvious that he had not come there by accident. He had a rope around his neck. His arms had been tied behind his back. The bindings disintegrated as I worked. His eyes were shut and his lips were slightly parted as if in a curse or a plea for mercy. Had he been a victim or a criminal or a sacrifice to the bog? All we could assume was that he had lain under the rock for four millennia and even that was only an educated guess.

By late afternoon his upper torso and left side were clear but, tempting as it was, we could not lift him yet. There was no way of knowing if his right leg was tucked under him or stuck down at an angle in the earth. Lifting him at that stage might have damaged the body and risked losing information from the burial.

His preservation was remarkable. Jo reckoned that the rock itself had protected him once the bog retreated. His skin had been cured in the peat, the stone weighing him down like a saucer in a jar of pickles. When all the surrounding peat had been dug the acidity had remained high enough beneath the stone to prevent any further decomposition.

The students set off for their lodgings at seven, ghoulishly satisfied by the excavation so far. They were staying half a mile away in a bothy little better than a byre.

After they had gone Jo stood over the pit considering how to proceed. His head had been shaved on the day of his death. The barber’s hand had shaken while he worked, the little nicks still visible on his scalp. This lack of hair meant taking a small skin sample for analysis instead. After a brief discussion she cut a strip from under his left arm. Some mummies are so well preserved that the skin still retains some elasticity but this is rare in naturally-mummified bodies. His skin was as dry as old bark. The body twitched when she cut into it.

“Damn. The sinews are drying out already.” She dropped the fragment into a jar and screwed down the lid. She turned to me. “Is there any way you could get him out tonight, Alistair?”

Clouds lay in an indigo smudge on the western horizon. I hesitated. The team usually avoided asking me direct questions but it had been a long day. I knew she would be disappointed which made my stammer worse.

“It’s p-p-past s-s-seven now. G-G-Gunner could rig up arc-lights I s-s-suppose… I couldn’t f-f-finish before m-m-m-morning.”

“Oh well. We’ll have to guard him, you know. The first thing those bloody students will do is post their photos on the internet. The place will be crawling with trophy-hunters by tomorrow.”

Fortunately we were staying nearby. Gunner, Jo, and I all live north of Newcastle, but William lives seventy miles away from Ford. He’s the only one of the team who is married. He often mentions his wife’s antagonism towards his rugby club and laddish mates, but not how she feels about his digging. He had booked us into a local farmhouse bed-and-breakfast for the job. The arrangement suited us all. Gunner can’t afford to run a car let alone a mortgage or family. Jo divorced years ago and lives with her older sister and three cats.

We all have our reasons to look forward to these tax-deductible jaunts. They save me from British Archaeology, last Wednesday’s Private Eye and Delia Smith’s Cooking for One.

William took the first shift. I dropped him off with fish and chips and a four-pack of Guinness to alleviate the tedium.

We ordered our meals in the pub at Etal and went to look for a table. The students were already eating by the fire. They called us over.

“Good idea, you can help celebrate our find,” Jo said. She sat down and patted a chair next to her so that I didn’t dither.

Annie was on my other side. The smell of fresh shampoo and damp hair wafted across me.

I offered to buy a round mainly by sign language. They accommodated my stammer because I was buying their drinks. Gunner went to the bar for me without needing to be asked. He’s good like that.

“How old do you think the mummy is?” one of them asked.

Jo had told them all several times that afternoon already but thankfully she did not feel obliged to remind them. Various theories were put forward as to who he was and why he had been killed. I am not a post-processual archaeologist; I can’t see the wisdom of imposing our mores on the finds of the past. I see what I see and avoid speculation. Gunner and Jo were in their element, though.

Annie was the only one apart from me who did not offer an opinion. She was drinking a bottle of something sticky and blue through a straw. I felt someone ought to stop her. She looked about ten, quietly perched on her stool, ready for bed.

She only spoke once. Gunner was hypothesizing that the carving on the rock suggested it was a boundary marker or had some religious significance. Being found under such a stone would indicate that the bog-man was an executed criminal.

“I don’t agree with capital punishment,” Annie said, gazing into the fire.

“Good,” I said.

I don’t know if she heard me.

We dropped Gunner off at the dig on the way back from the pub.

William was mellow with the Guinness and sloped off to bed as soon as we got back to the farm. Jo and I had a nightcap sitting on the patchwork quilt on the bed in her room.

“God, those students were tedious.”

I nodded.

“You seemed to be getting on well with that mousy little thing.”

I shook my head at her.

“You were very fluent when you asked her what she wanted to drink.”

“Uh.”

“Interesting. . . .”

“S-s-stop tr-tr-trying to s-s-s-psychoan-n-n-n-” I gave up.

Jo was looking at me like a bear that had stumbled across a picnic party. “Your secret’s safe with me.” She patted my knee and drained her glass. “Don’t fall asleep: your shift starts at two.”

The night was crisp and dark. I followed the grassy path along the brae from the gate in the starlight.

Gunner looked tired and grim.

“E-e-everything OK?”

“No it isn’t. This bloody bog is alive. I’ve been sitting here shitting myself for the last three hours.” He jumped as vixen barked just beyond the pool of lamplight.

I almost laughed, but a low hissing noise some distance away stopped me.

“No bloody idea what that is,” Gunner said in a low voice. “I’ll stay if you want me to.”

“You g-g–go and get some sleep. I’ll be f-f-f-”

“Look, are you sure? If you want the company-”

I shook my head and smiled. He slapped my shoulder for his reply, as though he, too, had trouble with words.

I shrugged off his concern and made myself as comfortable as I could. I heard the Land Rover start quarter of a mile away and briefly made out the headlights bouncing around before the track veered away towards the farm and Gunner’s bed.

He was right. The bog was a living entity, entirely organic, a growing mound, shedding its water onto the lag that circled it.

I had never been on the Moss in the dark before. I tried to experience without analysing, but it was impossible. Gunner had hung the lantern on the overhanging branch of an ash tree, just beyond my reach. The feeble light was the brightest thing for a mile in every direction. I felt vulnerable and would have preferred to be in the dark so that I could see further into the night. I was surrounded by constant movement and the sporadic rustle of nocturnal wildlife made me jumpy. By half-past two I was sitting bolt upright, straining to decipher the cacophony.

It was the lag that oozed and gurgled out there in the dark. The conifers in the plantation behind me were still discernable in the starlight, black against black, creaking without rhythm. The polythene sheet covering the body trembled in the breeze. Dark things flitted above me. I turned the deck-chair so that my back was to the bog man. The last thing I needed was to dwell on the horrors of death in this forsaken place. I remembered my flask and drank some of Jo’s whisky.

Sleep took me unawares. Despite the night chill and the sagging deck chair, I nodded off at some point. The next thing I knew Jo was shaking me awake. There was noise and confusion on the Moss, men shouting, their words lost in the cold sea fret. The sky was already light, the sun brimming over the sea but not yet spilling into the valley. Jo’s face was tight with anxiety.

An early morning dog-walker had found Annie. The police already knew about the dig, and that we were going to be there overnight. They had come out expecting to find a dead archaeologist, not a child.

There had been no attempt to hide her body. She had been carried from the students’ rudimentary sleeping accommodation to a thicket of goat willow only a few hundred yards from the dig. There she had been raped and murdered while I slept.

It was understandable that the police accepted that her fellows had been sleeping too soundly for her abductor to wake them. It happens. I saw the students in the grey morning light, wan and sickly and hung over. It was less forgivable that the officers did not believe me. But then, I had no alibi. Somehow the attack had not roused me. Worse, the tools her attacker had used had been taken from one of our equipment boxes. The plundered contents were scattered across the turf less than twenty feet from where I had slept. Her mouth had been stuffed with my gloves and her throat had been slashed by my trowel.

I didn’t see her body. When I had just spent so much time in close proximity to a dead man whom I could never know it seemed unfair, somehow, that I did not see her. Stupid to think there was a connection. But shyness is a bond of sorts, when you find it hard to make any others.

By half-past nine I had been arrested. Neither Gunner nor William would look at me. Jo jerked her chin up as I was led away, embarrassed to acknowledge me but doing it all the same.

I was taken to Berwick police station for questioning. The medic was gentle and sympathetic and made me so nervous that I fell mute, complying with his mortifying requests in silence. Then he abandoned me in a room with angry, impatient detectives. I was so appalled by this train of events that I could not ask for a glass of water, much less a solicitor.

“Do you understand why you were arrested?” one of them asked, speaking loud and slow.

A uniformed officer standing by the door sniggered when I tried to reply. Then they all piled in, bombarding me with questions.

“Did you find her attractive? Why was she the only student you spoke to? Did she ignore you? How did that make you feel?”

If only the police would shut up so that I could have space to think. It was so hard to concentrate on what they were asking. Their repetitions confused me. I stopped trying to answer them and let them infer what they wanted from my silence.

The time I spent in the cell was a relief. I sat for hours at a stretch, cross-legged on the squeaky plastic mattress cover, thinking about Annie.

I was sad about my trowel, too. Shameful to mourn over such a trivial thing in this situation but the silk-smooth wood had fitted my hand so reassuringly. It had its own smell. You notice these things when you spend most of your working life in small holes with your face pressed up next to your work surface. The edge of the flat triangular blade was razor sharp from daily contact with sand particles in the soil. No longer mine; now it was bagged up, to be used as evidence against me.

They could have let me out a day earlier, when my DNA samples came back negative, but they had become fond of the idea that I was a killer and were reluctant to let me go.

I rang Jo. They were still on the Moss. They had been allowed to return to the dig that morning. She half-heartedly suggested I could meet them there. I didn’t know where else to go.

Most of my morning was taken up travelling by public transport. The Land Rover belongs to me, as does most of the equipment. Resentment dulled the pain of returning to the site.

William was filling in the excavation beside a stack of turfs cut ready to cover the hole. He grunted acknowledgement without looking up.

The body of the bog-man lay on a plastic sheet, curled up in a foetal position. It seemed, as all mummies do, pathetically small. Perhaps he had been unjustly accused, too. Bile suddenly filled my mouth. If this had happened a hundred years ago I could have been hung for Annie’s murder.

Gunner usually saw to supplies. He had not bought lunch for me.

It was awkward. I was tainted with suspicion. The police had seen to that.

My team had told the detectives about me, my inability to form adult relationships, my shyness, and the stammer which disappeared when I spoke to children. Perhaps Jo had even mentioned how I looked at Annie. I doubt they felt disloyalty, given the circumstances.

While they ate I took a spare bottle of water and walked to the place where she had died. There was no guard now, days after her murder. A solitary bunch of cheap flowers had been propped against one of the iron bars holding the incident-tape. The students had clubbed together to buy her the tribute. I stood a few yards away from the taped-off area and wondered why the hell I had not heard her. The dig was clearly in view. I could hear them talking, see their faces turned towards me.

I walked over to the middle of the Moss. The peat is over twelve metres thick in the centre, too dry and acidic even for the scrubby willow. The breeze rippled the cotton grass and the whole place seemed to whisper. It is difficult for the mind to realise what the eye is seeing when you stand on a dome in the middle of a valley.

A straggly line of school children was weaving its way from the picnic site. The wind carried the teachers’ continual commands: “stay in your groups,” “keep me in sight,” “don’t go on to the bog alone.” All bogs are treacherous.

I turned back towards the dig but had not gone far when the tone of the commands changed to panic, twenty voices piping, “Hannah, Hannah.”

There was a thin scream close by and I pushed through the heather and willow to find the child crouched in terror, trembling all over. I had her in my arms before I realised what I was doing.

She clung to me, too badly scared to be coherent. She had wandered off from her classmates and something more than the emptiness of the Moss had frightened her.

I bundled her safely in my jacket and carried her to the centre of the bog. As I bawled at the distant, scurrying figures the hair rose on the back of my neck and my forearms and I knew with certainty that I stood now where others had stood throughout the millennia, crying out to strangers.

Even though I understood the gravity of my situation, I was glad I was the one who found her, saved her at least when I had not saved Annie. Glad enough to endure the vitriolic disgust the officers levelled at me. It felt like atonement.

Despite the best efforts of the police that afternoon Hannah refused to accuse me of abduction. They took their frustration out on me, called me every name in their limited vocabulary and eventually resorted to slamming my face into the table. I still couldn’t give them the answers they wanted. I was returned to my cell, shivering in paper overalls, numb with injustice.

The detective who briefed me before I was allowed to leave made it plain that I had been lucky, and my luck would fail one day. I would have made such a good candidate for a child killer. I took his disappointment into account and held my tongue.

Jo and Gunner had returned to the dig to take the final GPS reading for the rock. They were packing away the Total Station equipment when I arrived.

“They let you out then?”

‘I only f-f-found her, J-J-Jo.’

“Yes. I know.” She yanked a measuring pole out of the ground, “What happened to your eye?”

“W-walked into a d-d-d-d-”

“Going to do anything about it?”

I shook my head.

“Here, take the tripod, Gunner.”

Gunner came over and began to dismantle the tripod without looking at me. I picked up the plastic crate with the rest of the kit and trudged to the Land Rover. I waited for him. He had my keys.

He tried his best to avoid me, but Gunner is incapable of rudeness. I stood in front of the rear door so that he had to speak to me.

He looked up briefly and winced at my bruises.

“Alistair, I don’t know what to say.”

“I did-d-d-”

“I know. I know. But I just don’t feel it yet.”

“N-n-not the only w-w-w-one.”

“That poor girl.” He swung the equipment into the Land Rover. “I hope they catch the bastard soon.”

I had less confidence in the police, having had more experience than Gunner. I didn’t want to disillusion him. There were no other suspects.

“W-w-where’s W-W-William?”

“He’s gone to see the County Archaeologist. Oh God, you don’t know. . . .”

Jo launched the measuring pole past my ear into the back of the Land Rover. It landed with the clatter she had intended. I stared at her.

“Yes. While you were busy some bastard stole our bog man. The most significant find we’re ever likely to make.”

One look at Gunner’s face told me she wasn’t joking.

“W-w-when?”

“Yesterday. With all the fuss over that poor little girl we didn’t realise.”

“H-h-have you t-t-told the p-p-p-”

“What do you think? I got a lecture on priorities. The County Archaeologist has taken it out of our hands, anyway. Fortunately he isn’t hampered by having a suspected paedophile on his team.”

“Jo!”

“N-n-no G-G-Gunner, she’s right. B-b-bloody c-c-cock-up.”

Jo glared across the bog. “I hate this place,” she said.

I dropped them off on my way home.

I almost didn’t bother to check the kit. But there was comfort in the discipline of routine. The mounting screw for the Total Station was missing from its cavity in the plastic case. It is an expensive bit of kit, useless without the screw. I rang Jo to see if she had put it in her pocket by mistake. Jo dislikes implied criticism as much as the next man and I was relieved when she didn’t answer. I left a message in case she found it and decided there would be enough daylight to look for it if I set off straight away.

The dents in the bleached grass showed where the tripod had been that afternoon. I tuned the metal-detector. I was concentrating and did not notice the wiry figure crouching a few yards away behind the rock until he moved, startling me as he bolted for the trees. I had been consumed with my own innocence, not stopping to consider another man’s guilt. I had forgotten the murderer.

I called out. There was no reply. I scanned the plantation but the trees were planted so close that there was impenetrable night only a few feet in. I got back to my search for the screw, kicking and scuffing tussocks, listening and watching all the while.

As I walked over to the rock I caught a fleeting, predatory movement in the plantation. I swung the detector through its arc. There was a low growl from among the trees. Words, oaths, I don’t know. The meaning was plain enough.

I straightened up, holding the detector like a weapon.

Suddenly Jo called from the edge of the plantation. She was waving a small bright object in her hand.

As I turned back he sprang, black and wiry, knocking me over and landing on top of me, grabbing hold of my throat with both hands. I clung to his wrists. His skin was cold and dry as sandpaper but his muscles moved like pistons. We rolled down the bank together, face to face. He had no breath but for one hideous moment stale, stinking air flowed from his mouth across my face. Jo launched into the fray, gouging her fingers into his eye sockets until he let me go. I dragged myself from underneath him and smashed the detector across his shoulders. He crouched, snarling and covering his head as I continued to hit him with the broken shaft.

I wanted to kill him. For me, not them. He was what I could never be, should never be. He had no blood to spill and no breath to stop but I swear I would have ripped his skin apart and scattered his bones to the four winds if Jo had not stopped me then.

She grabbed my arms from behind and screamed into my ear, “You can’t kill him. Run, now.”

She was right, of course.

He stood up. Not small and vulnerable anymore, but tall and virile, his noose still around his neck. He dodged behind the rock, patted it and bared his teeth. He was laughing at us as we ran.

How could we report it? Jo refuses to even discuss it with me.

Four millennia ago our ancestors buried this thing under the Moss. We have let it loose.

So I come up here and watch the children, just as he does.

____________________________________________________________

Rowan Bowman is the first-ever two-time winner of The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award competition. Her previous story, “The Beast of Blanchland,” took top honors in our Summer 2018 contest. Rowan spent her early childhood in Uganda, but has lived in the North East of England since the age of five. Her first novel, Checkmate, was published in 2015. She has had several short stories published, and two short stories, “The Collection” and “The Apple Tree,” won first and second prize in the Dark Times competition in 2012. Rowan has a PhD in English and Creative Writing from Northumbria University and is currently working on her second novel, On Barley Hill. Her work always has a horror element and strong narrative connections to the haunted landscapes of Northumberland.

Rowan Bowman is the first-ever two-time winner of The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award competition. Her previous story, “The Beast of Blanchland,” took top honors in our Summer 2018 contest. Rowan spent her early childhood in Uganda, but has lived in the North East of England since the age of five. Her first novel, Checkmate, was published in 2015. She has had several short stories published, and two short stories, “The Collection” and “The Apple Tree,” won first and second prize in the Dark Times competition in 2012. Rowan has a PhD in English and Creative Writing from Northumbria University and is currently working on her second novel, On Barley Hill. Her work always has a horror element and strong narrative connections to the haunted landscapes of Northumberland.