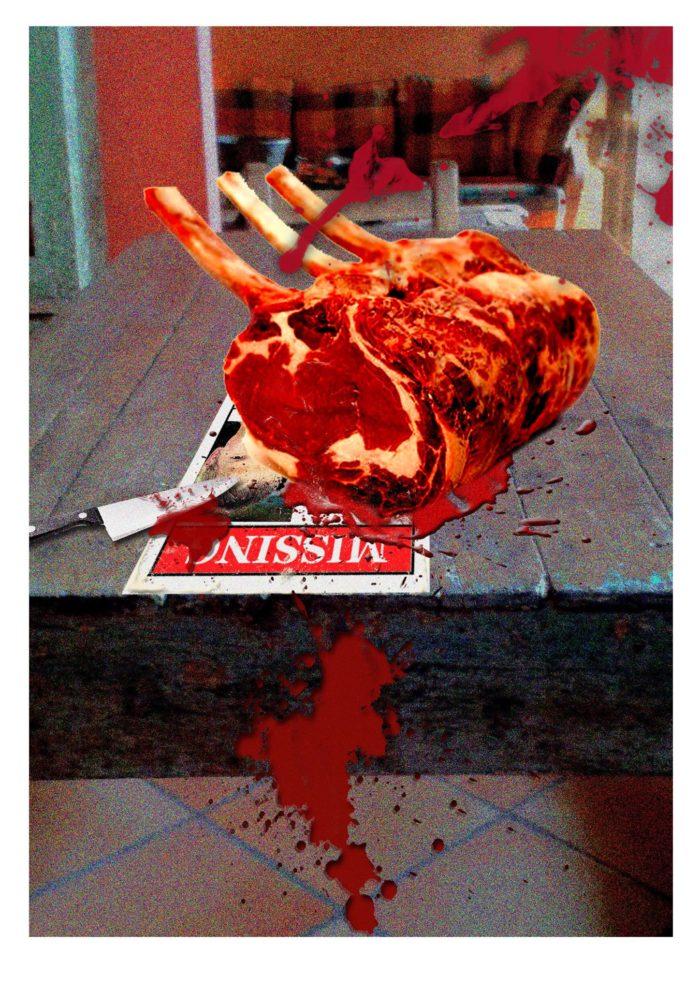

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

HONORABLE MENTION, FALL 2019

BY PAMELA JOHNSON PARKER

“A face to meet the faces that you meet.” — T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

You watch Georgia sleeping, the curve of her shoulder like a three-quarter moon risen above the horizon of navy comforter the two of you had picked out at Dillards, back when she used to go places with you, when she didn’t sleep the summers away.

She sleeps all day these days, your daughter. Remember how you used to plead with her to take a nap, but she’d never sleep when you wanted, and now when you want her to wake up, enjoy the afternoon sunshine, ride her bike, go for a walk, anything. Nothing.

You watch her, and you think, I made that. And you think, How can anything be that lovely?

And you think, I used to be that lovely.

Georgia tells you, in a whisper, when you try to wake her, Mama, just let me sleep. I’ll be up tonight.

That’s what you’re afraid of. That she’ll be up. All night. Tonight.

And you think of her father, for a second, and then you leave the room.

Georgia looks so thin, so exhausted. Circles under her eyes nearly as dark as that comforter. A pearl-blue bruise, so faint you can barely see it, over her neck.

These days, you can see her ribs, can count every bar in the birdcage that holds her heart.

Such a simple request, for a mother, to want her daughter to eat.

I’m not hungry, Mama.

First, a stray puppy, throat torn open, drained of all its blood.

Next, the neighbor’s tomcat, nothing left of him but fur and a front paw. Folks murmur Coyotes, even this close to town; start keeping their own pets inside.

And then Alex Chandler, age 7, who lives two blocks over, goes missing for a day and a half. He’s found, but he can’t (or won’t) talk, and his neck is hurt, a detail that they keep out of the Messenger but not out of the gossip you overhear at the Stop-N-Save.

Georgia’s your only child, your lookalike. Folks say she favors you, the apple not falling far, something you can’t countenance in your own countenance, a reckoning you didn’t reckon on. Her pale skin and black and blue eyes are yours, but not that neck— a swan’s. Neither of you can understand where it came from, so you both looked through photographs with white-deckled edges rippling like waves on sand.

There are no pictures of her father in any of the albums.

There are lots of pictures of you. You used to mug for the camera. You were a beauty; you can see it in your high school and college yearbooks. You know it’s passed you by, that it’s Georgia’s turn now, to turn heads.

And she’s turning.

Since she turned 13, Georgia’s stopped asking about her father, which is a good thing, you think at first. Then you think maybe she’s learned something, something you’ve been trying to hide all these years. Then you think she’s met him, maybe online, and that’s why she’s avoiding you, like she doesn’t even see you.

No one sees you these days. You’re invisible.

You remember how he saw you.

You remember how he lifted your hair away from your neck, the at-first-gentle graze of his teeth.

You remember being wanted, him waiting outside your window, asking to come in.

You remember how he’d never move in with you, even though most nights he’d come by, a cat in the alley caterwauling.

You remember how he told you You taste different, after you’d missed your period.

You remember how he left you alone.

You remember when he left you for good.

You threw away everything he’d left behind, except Georgia.

You never want to think he’d be back, that she’d see him, that she’d see herself in him.

It’s late afternoon, almost dusk, what the French call the hour between dog and wolf, when darkness like a shawl falls over the horizon, when the rising moon glints silver over the lavender that lines your sidewalk. Like spilled mercury, you think, which sounds like when you used to write poetry, before Georgia, before the chemo.

You remember your hair thinning, falling out. You remember marrow, spleen, bone, platelet counts. You remember the silver sheen of the x-rays, the platinum in Cisplatin, one of your chemo meds. You remember how pale you were. How scared. How you couldn’t sleep without a light on, even at 35.

You remember transfusions, all that blood dripping, how Georgia was fascinated by the very idea.

You used to like the dark. Your favorite painting, “Nighthawks,” takes place in a diner, in the dark, where people gather around an old zinc counter, sipping coffee, ordering one more slice of apple pie. Streetlights halo the darkness that enfolds them in an unearthly green, the color of absinthe. It takes you years and years before you notice what Hopper did, how there’s no door, no way in or out, and the short-order cook, the men in suits and fedoras, and the curvy woman in the red dress who has equally red hair, are trapped like specimens in a bell jar.

Why are you thinking of that painting? Is there someone other than you, the viewer, looking on, wanting in?

The first time he kisses you, undresses you in your basement apartment, you’re pale and shivering in the half-dark room and him even whiter. Lustrous, you think, and think how you sound too poetic. But he is beautiful, and he is yours, and he spends hours and hours kissing you.

Your friends tease you about him. All those hickies.

All the times he’d nurse on your neck, leave bruises, even blood a couple of times when he’d bite too hard.

You’d nursed Georgia for the first year, but then she’d gotten teeth and bitten you, till there was a little half-moon mark on each of your breasts. You stopped, and she started using a sippy cup.

She’d taken the milk from your body, the calcium from your bones; she used to swim in the silt of your uterus. You’d shared the lifeline of the umbilical cord. Your blood kept her alive.

Flesh of my flesh, bone of my bone.

What keeps her alive now? you wonder. She’s scarcely eating.

In the kitchen one evening, you pull every pot from the rack, every pan from the cabinet, every spice from the drawer. From the butcher’s you’ve bought a standing rib roast that’s big and bloody, marbled with fat—way too much meat for only two, but you don’t care. Its seven ribs make a basket that you’ll tie with string and stuff with vegetables from the farmer’s market. You’ve chosen turnips with purple tops and white bases, which will act as sponges for the au jus that will seep from the roast; carrots crisp and bright orange, which will mellow to a beautiful shade of caramel; potatoes with their misshapen ovals and earth-brown jackets that will crisp and darken as the roast browns; pearl onions that will melt into the roast and disappear, leaving only their fragrance and flavor behind. You’ll coat the papery fat of the roast (the fell you learn from the cookbook) with mustard seeds and slide it into the oven. So succulent, you think, so tempting.

As you carve little runnels into the meat to stuff with the pearl onions, somehow you falter and slice open your hand. Blood seeps from the cut; the onion juice that’s still on the blade stings your skin; the bright rubies of your blood mingle with the deeper garnet of the roast.

You don’t make a sound, but Georgia stumbles into the kitchen.

Mama? She stares at the cut on your hand, at the blood on the roast, on the knife, on the cutting board, on the butcher-block counter. Stares and stares until you have to look away and leave the room on the pretext of looking for a bandage.

When you return, Georgia is nowhere around, but the counter, the cutting board, even the crescent blade of the knife are spotless, and the roast seems much, much more anemic than you remember.

You take the roast, the vegetables, even the cutting board and your best knife, out to the trash and bury them as deeply as you can.

More cats.

More dogs.

A calf from the fields behind your neighborhood, and a horse from the local stables, only the hides and hooves remaining.

You lie in your own bed, most nights without a lamp burning, look up at the net of stars through the skylight; you watch the crescent moon like a sickle cutting through clouds. Sometimes you remember him, at your window. Sometimes you imagine him back, imagine the constellation of your family put together again—mama, daddy, baby. But constellations have back stories, you learned in Humanities, and none of them is pretty. All of those Greek families have a death. Think Odysseus, think Jason, think Medea.

Sometimes you wonder how your own story will end, how you’ll end up, how you’ll end it.

It’s twilight now, and she’s sleeping. So still, so beautiful.

On the News at 6, you discover that another little boy’s missing. SUSPECT SOUGHT IN DISAPPEARANCE, reads the headline at the bottom of the screen, right before the baseball box scores. You used to love baseball.

And you remember how you used to love games. You’d play Hide-and-Seek with Georgia. You remember playing Which Hand—one would hold a penny, the other might be empty, might hold a dime.

Your hands aren’t empty now.

Behind your back, you hold a croquet mallet, a garden stake you’d planned on using for tomatoes.

Mama, she mumbles, and smiles up at you. When did her teeth get so straight? What big teeth you have floats into your mind, a line from a story you’d read to her before naps, when she was three, when she always rooted for the wolf.

____________________________________________________________

Pamela Johnson Parker lives in Kentucky and works in the Department of Art & Design at Murray State University. Her fiction, poems, and essays have appeared in diode, Upstart Crow, Gamut, American Poetry & Journal, North Dakota Quarterly, KYSO Fiction, and Anomaly, among others. She is the author of Cleave (2018 Trio Poetry Award), as well as the chapbooks Other Four-Letter Words and A Walk Through The Memory Palace (Qaartsiluni Chapbook Award). Her She has been nominated for Best American Science and Nature Writing, and her work is also featured in the Out of Sequence: Shakespeare’s Sonnets Remixed, Best New Poets 2011, and Language Lessons: Vol 1.

Pamela Johnson Parker lives in Kentucky and works in the Department of Art & Design at Murray State University. Her fiction, poems, and essays have appeared in diode, Upstart Crow, Gamut, American Poetry & Journal, North Dakota Quarterly, KYSO Fiction, and Anomaly, among others. She is the author of Cleave (2018 Trio Poetry Award), as well as the chapbooks Other Four-Letter Words and A Walk Through The Memory Palace (Qaartsiluni Chapbook Award). Her She has been nominated for Best American Science and Nature Writing, and her work is also featured in the Out of Sequence: Shakespeare’s Sonnets Remixed, Best New Poets 2011, and Language Lessons: Vol 1.