SECOND HONORABLE MENTION, SUMMER 2018

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

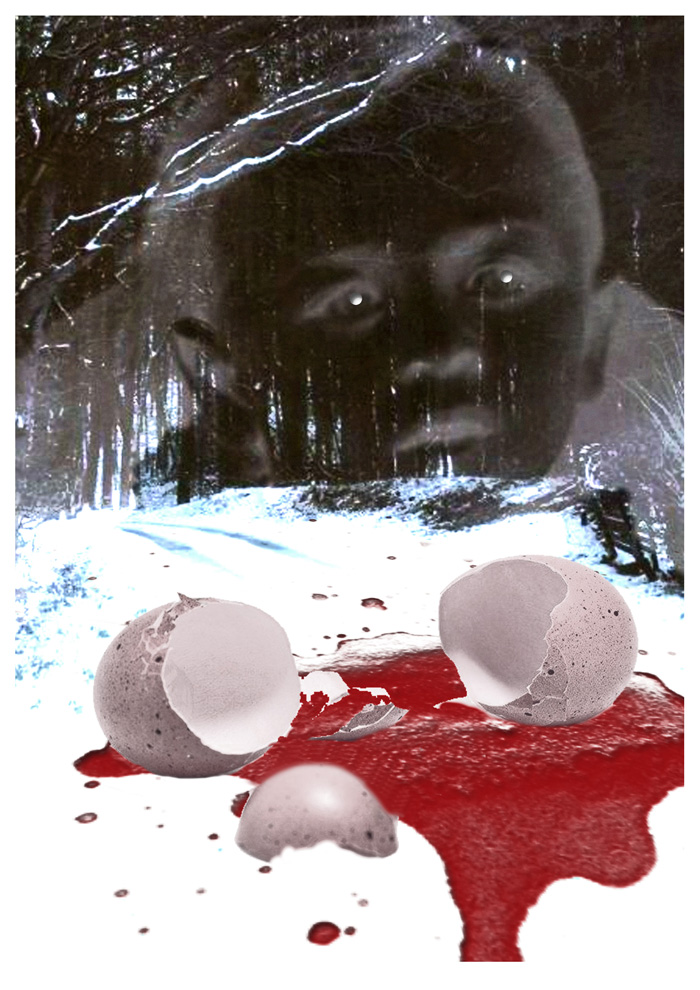

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY MEG SIPOS

The Problem

The thing in the crib is definitely not her child. Fairies—the Fae—have stolen him. The thing is shriveled. A thin, mangled twig swaddled in blankets that just won’t. Stop. Shrieking. It wails Shay awake, night after night, and she does her best to hush it back to sleep, but nothing works. Nothing. Nothing works.

How could she care for a twig that barely resembles her beautiful stolen boy?

She tries to think of other explanations—because fairies sweeping her boy out of his crib in the dead of night is ridiculous, but her baby boy hadn’t even reached his first birthday. He couldn’t have just crawled out of his crib and waddled out of the house. And even if he had, surely he wouldn’t have gotten far. She would have heard his nighttime shuffling or his morning giggle or frightened hiccups if he had. Surely.

It’s been two weeks of trying to shush the shrieks of the thing. She is convinced. Fairies have taken her Danny. Her friends and neighbors are solemn when she tells them. They nod in understanding, but they also warn her that the Fae don’t just return the children they’ve taken. Especially not Danny, with his rosy cheeks and jingling laughter and twinkling blue eyes.

Hasn’t she been paying attention?

Potential Course of Action #1

Mary Robertson from across the street tells her that she has to take that thing (that thing that is not her son, let’s be clear) and saw it into pieces. “Also, this tea is still a bit too hot. Would you please pass the cream?”

Shay grasps the tiny carafe with two fingers and leans over the cherry-glazed coffee table, over the tray full of biscotti, crumb cake, honey, and the old stoneware teapot that her grandmother left her—decorated in creams and greens, embellished with Celtic knot work—and hands it to Mary.

She thinks about what Mary is telling her. She doesn’t have much experience with using saws. She remembers taking woodshop in school. They asked her to make a clock and she nearly cut her fingers off when trying to split a board of wood in half with the table saw.

And a board of wood doesn’t shriek.

Mary pours herself a generous amount of cream and swigs down her tea. She wraps her entire woodworker’s palm around her cup, ignoring the handle completely, callouses immune to the heat.

“I’m not sure….” Shay says. It all sounds very messy.

“You can use my garage, if you’d like,” Mary offers.

She leans forward and reaches for the dish of honey, stirring a heap into her already half-finished cup of tea. Steam curls over Shay’s untouched cup. “I have a saw that will slice right through bone. And some earplugs you can use so that the screaming doesn’t get to be too much.”

The thing shrieks from upstairs. Shay shudders, curling her fingers as if each shriek were a splinter underneath her fingernails. “But what do you do with the…pieces?” she asks.

Mary takes another sip of her tea and leans back. Her left arm rests on the arm of the couch, left hand caressing the tiny punctures in the upholstery courtesy of Shay’s feline menace. She never really wanted the cat.

“Bake the dismembered parts of that wretched thing into a pie for you and your husband,” Mary says. “I have a wonderful recipe. Passed down from generation to generation.

“Boil the pieces first, of course. Once you do that, you’ll be able to mince the limbs. And then you can get working on the pie. We always drizzle on some white truffle oil and garnish with fresh herbs. Would you like the recipe?”

Potential Course of Action #2

Shay traces the splits that run through the wood of the bar and sips at her watered-down Old Fashioned. The bartender has been quite generous with the rye whiskey, but she’s been staring at the splits in the wood for so long that the ice has melted. She told Mary that she didn’t want that family recipe. She told her that she didn’t care for meat pies.

When Shay’s husband came home from work, he took one look at the lines forming on her face and shoved her out the door. She tried to protest. She didn’t want to subject him to enduring the wails of that creature all on his own the way that she’d been, but he simply shook his head.

“Go take a walk or something. Get some fresh air,” he told her as he wrapped his arms around her waist. “I can handle this.”

So now she’s sitting at the bar. Drinking alone until she’s not drinking alone anymore.

Her neighbor from down the street settles into the stool next to hers. She turns her head and nods. “How are you, Al?” she asks.

“The question,” he replies, “is how are you?”

He waves to the bartender and mouths a drink order before turning back.

“Tired,” she answers. “Husband’s at home dealing with…so I’m here…drinking.”

The bartender delivers a frothing beer the color of roasted chestnut to Al, who pulls out crumpled bills from the pocket of his dirt-stained jeans and places them on the counter. Al takes a sip of his beer and some foam lingers on his lip. He doesn’t wipe it off. The tiny bubbles burst and dissolve. “I hear you’re squeamish about the pie,” he says.

Not just the pie, Shay thinks.

“It’s all the slicing and dicing and mincing. Nearly cut my fingers off in woodshop however many years ago. Haven’t used tools like that since.”

Al nods. “You do want it all taken care of, though—don’t you?”

Of course. She wants her son back. The words claw at the smoke twirling above their heads. Al nods again. And then nods some more. “Bring the thing to my place. I got a wood chipper that will take care of everything. Quick and easy.”

“And what do you do with the…” she pauses for a moment, “mess?”

“Use it as mulch, of course. What else? Bet you could create a mighty fine garden with it. It’d be quite fertile.”

Shay thinks about Sarah Jefferson’s garden across the way and how lovely a garden in her own backyard would be. She could plant rose bushes and speckle the yard with sprigs of lilac. She could grow tomatoes and peppers and squash…she imagines a fairy tale-like place with stone paths winding through, arches and pergolas covered in honeysuckle, the gentle rush of a small stream that empties into a pond of water lily fish. An Eden in a City of Hell.

“I appreciate the help,” she tells Al as she lifts herself from the stool. “But even with the mulch, I don’t think I could compete with Sarah Jefferson.”

Shay might as well leave the gardening to her.

Potential Course of Action #3 & #4

A friend Shay hasn’t heard from in months—one of the lucky ones who got out of the city before it was too late to get out of the city and who’s been in Egypt studying cat mummies for the sake of studying cat mummies—rings when she hears the news.

Others have already told her that Shay can’t bring herself to slice the thing up or toss it in a wood chipper. Even if doing so would mean finally getting her son back. Leah wants to understand.

“Why?” she asks when Shay answers the phone.

“It does sort of resemble him.” Shay says. “What if I kill it and the little fu— I mean, what if the Good People still don’t give me back my Daniel? At least the stick is something of a reminder.”

Shay’s in the nursery. The thing that is not her son is in her son’s crib, wailing away. She’s learned to tune out the noise. She’s curled up in the corner of the room, on the rocking chair, huddling under the wool blanket and clutching a book that is meant to be an informative guide on all things Fae. It hasn’t taught her much.

Though she has taken to leaving offerings on the windowsill in her bedroom— chocolates, pieces of jewelry that her husband bought her that she never wore, a teacup from her grandmother’s set—she always wakes up to a bare windowsill. She knows that they’re accepting her gifts. So she doesn’t understand why she doesn’t have Danny back by now.

“I get it,” Leah says. “I do. It’s hard when it looks so much like your little boy. But, really, if you want him back, you’re just going to have to get over your squeamishness and…”

“Slaughter it?” Shay asks.

“Well, here’s what you do.”

Shay presses the phone closer to her ear and sways forward in the rocking chair.

“You’re getting a lot of snow right now, right?” Leah pauses. “Gotta tell you, I really don’t miss that place. Anyway, you just have to drive down the road and throw it out the window if you’re squeamish about the pie and the wood chipper. Or hell, drive to one of the city borders and toss it over. I doubt even the Gentry are immune to that. Let it meet the same fate as everyone else who tries to leave that shit hole—I mean, I’m sorry you’re still there and all…but this isn’t about that. This is about your baby boy.”

It’s the middle of February and the temperature has been at an all-time low. Snow has been steadily falling over the course of the week. It must be blanketing sheets of ice by now.

Shay thinks about this creature shivering in the cold, frost-bitten lips puffing out shallow breaths as it tries to cradle itself with its twiggy arms, purpled fingers permanently bent.

“Let it freeze and rot to dirt,” Leah insists.

Shay ponders this. She really does. But just because this twig, this enchanted stick or old, withering fairy—or whatever the hell it is—isn’t her son, well, that doesn’t stop it from resembling him.

“It’s just…”

Leah sighs into the phone. “Okay. All right. If you can’t…then there’s really only one thing that you can do. I heard once from my grandmother, who heard from someone she crossed paths with while traveling through Europe….You’re going to have to boil some eggshells. That’s the only way to know for sure. And if it turns out that that thing in your son’s crib is, well…” she pauses and Shay hears some static on the other line, “then you’ll know what to do.”

Boiling eggshells. No pie. No mulch. No leaving this thing to rot. Surely no screams. Surely less of a mess.

Boiling eggshells. This, it seems, is the only logical way forward. It’ll have to do.

The Results

Shay brings the creature that is not really her son, or that she doesn’t think is really her son, into the kitchen with her and sets it down, ever-shrieking, in the playpen by the kitchen counter. She pulls a carton of eggs from the fridge and places it on the counter by the kitchen knife she had used earlier to chop vegetables for omelets.

She cracks an egg, tosses the yolk and whites in the trash. Cracks another, disposes once more of the goop, all the while watching the stick from the corner of her eye. When she pitches the third round of eggy innards, the wailing that has been an ever-present part of her life these last few weeks finally stops. The little thing has pulled itself up to peek over the bar of the playpen and watch her. Intensely. Curiously. She continues to trash the yolks and whites, setting the eggshells on the counter by the stove.

Her hands are slick and sticky when she finishes cracking the entire carton of eggs, but she doesn’t stop to wash her hands. She brings out a big pot, fills it with water, and then sets it on the stove. The thing watches silently as the water boils and she fills the pot with the eggshells.

An old, tiny voice startles her. So small. So…shriveled. “What are you doing?” Its rasps scratch at her throat. Shay stops, but she can’t bring herself to turn and face the creature posing as her son. The voice is enough to let her know for sure what she is dealing with.

“Well, sweetheart, I’m boiling eggshells.” What else can she say? And what else can she do but hope that the tremor in her own voice is light enough to go undetected.

The creature is silent for a moment, still peering over the pen, she guesses. Then she hears a hoarse, “Why?”

Shay doesn’t answer. Because, again, what else can she say?

But then something comes to her. Just like Leah said she would, she now knows what she has to do. It’s all very clear.

“Why don’t you come help? Would you like to do that? And then I’ll tell you why I’m boiling these eggshells.”

Shay hears a shuffling noise, but she doesn’t turn around. Instead, she grips the kitchen knife lying on the counter. She’s ready to strike, ready to demand the return of what was taken from her.

She listens as the patter of little feet comes closer and her grip on the knife tightens. When she’s certain that the creature is close, she swings around, intent on gutting the tiny being.

But she misses. Of course she misses. This is a fairy, an enchanted being. Of course it knows. Because its eyes instantly widen at the knife in her hand and its shriek causes her to drop her weapon and clutch at her ears, and she watches as it disappears into thin air.

And then silence.

Shay rages into that silence: “You give me back my baby boy!”

No one answers. She sweeps the knife up—notes how much she needs to mop because there are still Kix scattered across the tile from that night she stumbled in drunk and hungry but couldn’t trust herself to cook—and scours the rooms with a fury she’s never felt before.

“Where are you?”

Of course no one answers.

So she listens. She waits. And then she hears something.

A noise escapes from the nursery. It’s almost like a gurgle. Shay is certain that the creature has taken refuge there, but she knows that won’t last long. Because now she knows where it is. She creeps into the nursery. The window is open, blowing the curtains over the crib. She can see the tiny silhouette. She approaches, knife raised. She has to do this. It simply didn’t give her any other choice.

So she plunges the knife down as hard as she can and, in an instant, she hears a very familiar shriek of pain. One she hasn’t heard in weeks.

It stabs her in a way that nothing has before. The stillness of the moment grips her and twists her stomach. An aching hollow settles inside as she stands over her son’s crib. Eventually, she forces herself to stare past her blood-spattered hands.

Her Danny. The fairies have finally returned him.

The Aftermath

Shay’s knife falls from her hand. She barely hears the soft clang as it hits the carpet. Stunned, she gathers her Daniel into trembling arms. The shrieking has stopped. The house is, once again, quiet.

The quiet is unbearably noisy.

She holds her son’s bobbing head with her hand. He doesn’t move. “It’s going to be okay. I’m here. I’m here now.”

The limp body she’s holding doesn’t respond, but she continues to hold it and rock it anyway. After thirty minutes of silent rocking, she puts it gently back into the crib. Swaddles it with the blue blanket she’s had since the day she came home from the hospital after two days of drug-shrouded labor.

Where her mother-in-law, who she never got along with, kept trying to spoon-feed her sauerkraut before the doctors could whisk her away—it’s good to eat right after your water breaks, the old hag kept insisting. Where she kept counting the fading stars in Spanish until she was the only thing left in the vast darkness of the universe. Where she frantically searched for her son under the hospital bed when she woke up and couldn’t find him. The doctors don’t use ether anymore. Not even in Erie, the-Saddest-Place-on-Earth, Pennsylvania.

Shay allows herself to sink to the floor and vomit on the carpet of the nursery. The vomit spills onto the bloodied knife. It glints red and silver. The dry heaves continue well after everything that was in her stomach is now on the nursery floor.

After her heaving settles, she starts counting in Spanish and pulls herself up by the rails of the crib. No one gave her advice for this. She thinks of Mary Robertson. She think of Sarah Jefferson. Of Al and Leah. Of her husband. What will they think? What will they say? She could have baked a pie. She could have had a garden. It was a fairy. A changeling.

It is. It still is.

It’s Danny who was.

No, she decides. It’s Danny who is. It’s this thing, this twiggy bit of soft, bloody wood that was. That’s what was.

She never got her son back, she tells herself. Her son is still gone. Missing. Whatever is in that crib is definitely not her son.

But at least it’s not shrieking anymore.

She’s taken care of this creature. This old fairy or enchanted stick or whatever the hell it was. Now she just needs to wait for the Fair Folk to bring her son back. They will. They have to. She just has to get rid of this thing that is not her son and wait. She can wait.

She goes to her bedroom closet. The shoeboxes are too small, so she pulls out her navy suitcase. That will have to do. She drags the suitcase to the nursery. Zips it open, places the creature swaddled in the blue blanket inside, and zips it back up. She drags the suitcase down the stairs and out the front door. The suitcase is light when she lifts it up and tosses it into the trash can. Then, she pulls the trash can down the driveway and places it on the sidewalk.

There’s a ringing in her ears. Like she can still hear the shrieking even though everything is quiet now. Shaking it away, she goes inside to make tea with the old stoneware teapot that her grandmother left her. She can wait.

Meg Sipos earned her MFA in creative writing from George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia and her BFA in creative writing from Penn State Erie, where she served as fiction editor for the literary journal Lake Effect. While pursuing her MFA in fiction at Mason, she worked as nonfiction editor for the feminist literary journal So to Speak before launching Bestiary, a podcast about humans and other animals, with her fiance, Eric Botts. She now acts as co-host. She and Eric dream of one day having a vegetarian restaurant with grotesquely-named but delicious dishes.

Meg Sipos earned her MFA in creative writing from George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia and her BFA in creative writing from Penn State Erie, where she served as fiction editor for the literary journal Lake Effect. While pursuing her MFA in fiction at Mason, she worked as nonfiction editor for the feminist literary journal So to Speak before launching Bestiary, a podcast about humans and other animals, with her fiance, Eric Botts. She now acts as co-host. She and Eric dream of one day having a vegetarian restaurant with grotesquely-named but delicious dishes.